I’ve been doing more cartooning (and teaching) than criticism lately, so I haven’t had much time to come up with new posts for this blog. But since Dawning of a Brighter Day up and running again, after several days’ rest no doubt, I decided I owe it something.

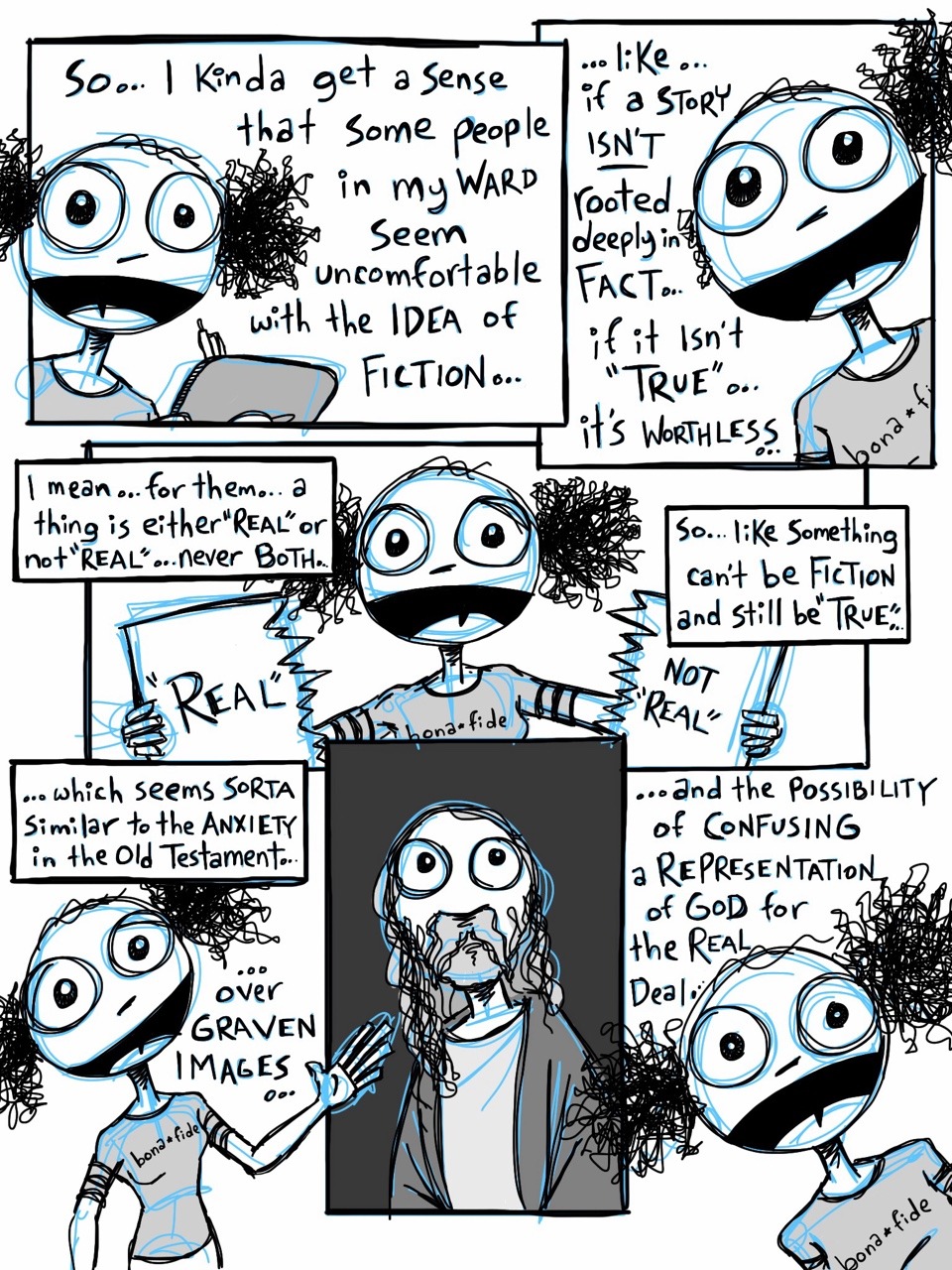

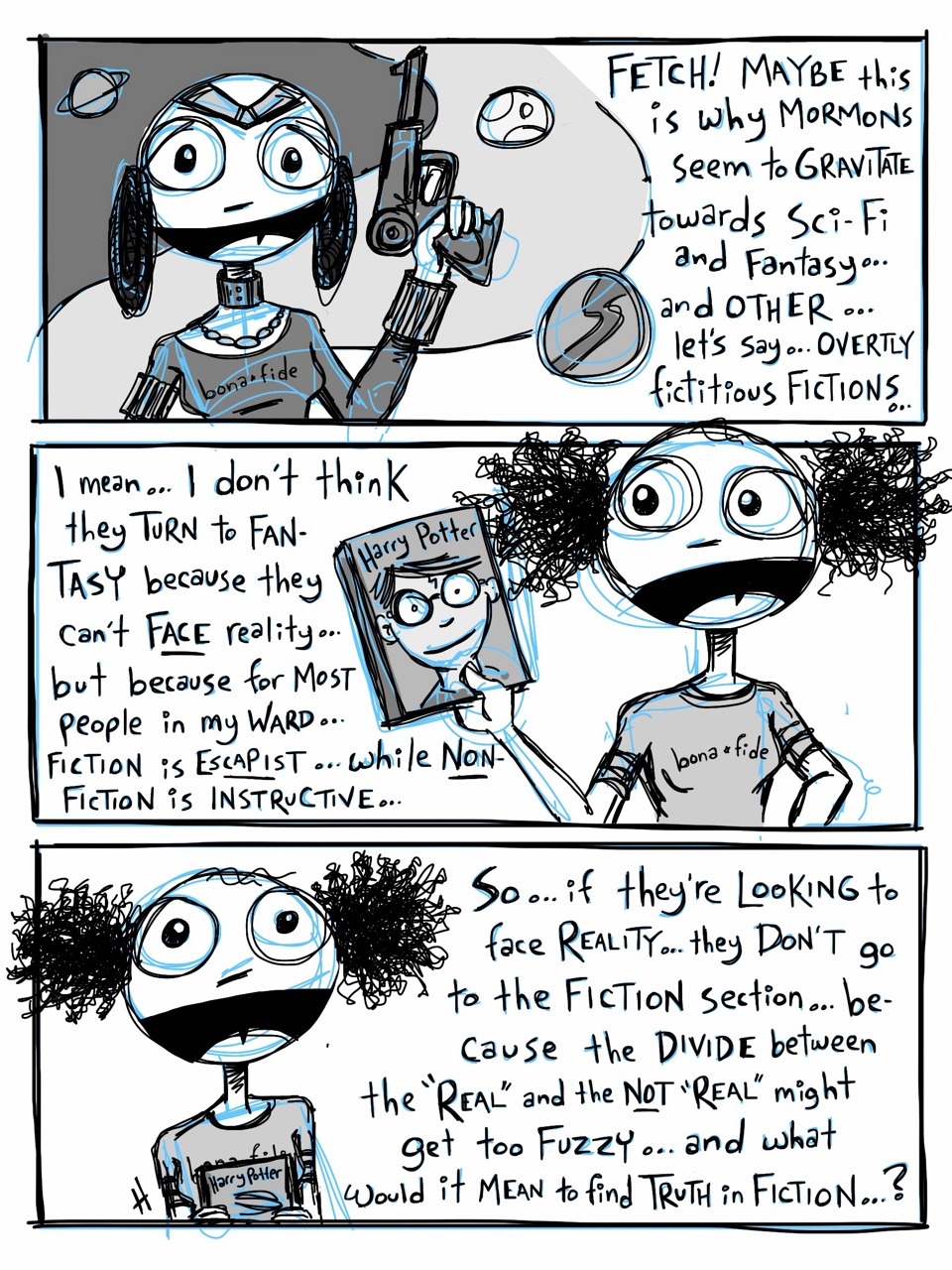

Below is one of my latest Enid comics–the second that deals specifically with Mormons and fiction. (The first appeared on this blog “pseudo-anonymously” several months ago.) In it, Enid tries to explain why members in her ward are “uncomfortable” with fiction, ultimately tying it in to ways Mormons–in America, at least–seek for truth.

What are your thoughts?

NOTE: I should say that I post this not to reopen the science fiction vs. realism debates, but to maybe invite new insights into the evolving role of fiction in Mormon society. Also, I also want to say that Enid’s grouping of science fiction with escapist literature is not to suggest that it is escapist, but rather that it often perceived and treated as such by readers seeking a reprieve from the daily grind of life.

While I agree with some of your observations, I think that explanations of causes are rather more complex than truth/realism versus fiction/escape.

Writing of his own desire for fantastic stories as a child, Tolkien noted, “Fairy-stories were plainly not primarily concerned with possibility, but with desirability. If they awakened desire, satisfying it while often whetting it unbearably, they succeeded” (“On Fairy-Stories”). Over time, I’ve come to believe that this suggests a profound truth about all fiction. Which, yes, may be one reason why we as Mormons (and Westerners) are sometimes dubious about fiction: because we view desire itself as suspect.

But again, I think this is overly simple — partly because I think different things are true of different people. There is a group of Mormons who distrust fiction. There is another group of Mormons that prefers to read contemporary entertaining fiction, rather than realistic fiction (e.g., cozy mysteries, light romances, etc.). There are the Mormons who prefer to read science fiction and fantasy. (I see Twilight-readers, by the way, as falling more into the second than the third category; but that’s a discourse for another occasion.) And probably there are more groups that could be broken out (e.g., readers of historical narratives — whether fiction or nonfiction — etc.).

What I have observed about these different groups is that they all seem to go to literature for different reasons. Even in cases such as my own where there may be a taste for more than one kind of fiction, I tend to go to different types of fiction seeking different types of experiences.

For me, the desire-paradigm is a potentially very fruitful one: what is the desire that the reader is trying to satisfy? Because there are different types of desire, and it seems to me that much of genre (including the more realistic genres) is best explained as a way of addressing those different sets of desires. (If I had ever been going to have a career as a literary theorist, this is probably the direction I would have chosen to pursue.)

More specifically, the (relative) dislike of realistic fiction by Mormon non-readers of fiction, readers of more “lighthearted” contemporary fiction, and readers of science fiction and fantasy seem to me to have three different explanations. A sociologist might find common cultural threads underlying those reasons, but it seems to me that those commonalities are possibly less interesting than the differences. In any event, we need to start with an analysis that takes into account those differences, both for political reasons (i.e., to avoid needless offense) and for methodological ones.

While there is, I think, some anxiety about confusing the real with the not-real among those who prefer not to read fiction, I think the more potent reasons are deeper than that (also true of ancient Israelites and idol-worship, I suspect). It’s not so much that non-readers of fiction think they might get confused about whether the Steeds actually existed, but rather that since stories *are* at some level reflective (and shaping) of desire, there is a need for caution in allowing them the power to do the same to us. Because desire can be shaped in both healthy and unhealthy ways. Nonfiction narratives can, of course, involve the same dangers — but I think that for those who prefer nonfiction, there’s a certain comforting sense that the reality of fixed events offers a healthy (there’s that word again) resistance to role of desire in shaping narrative, both for the writer and for the reader. This isn’t a view I particularly share, but it’s important to acknowledge as reflecting in some ways a fairly sophisticated understanding of fiction.

More to come, but I’ve decided that I need to take a break…

In contrast, those Mormon readers who prefer lighthearted contemporary fiction are not, I submit, suspicious of fiction as such — but they go to it for reasons that make them unlikely to want to read more challengingly realistic fiction. And I think there may be a peculiarly Mormon tinge to those reasons.

The gospel holds us up to an uncomfortably challenging standard. Most Mormons I know are not complacent, but actually quite anxious: about our families, the many responsibilities we fail to live up to, the condition(s) of the world, those on our various “please bless” lists, and the challenge to be constantly improving ourselves, among others. Such Mormons — and I am often one of them — find life quite challenging in itself. When they go to fiction — and some of them do so quite often — it is typically for relaxation (at its simplest level) or beauty (at a deeper level). This may be a kind of escape, but it is generally a temporary one — a little R&R before plunging back into the battle of life.

Mormon science fiction and fantasy readers (again, clarifying that I mostly don’t see Twilight-readers as falling into this category, just to keep my definitions clear), in their turn, may be said to be escaping from the mundanity of everyday life, but it is a different kind of escape. Analysis of well-known fantasy works from Tolkien to Rowling demonstrates that on a thematic level, these are dealing with very tough things: death and change, the complexities of right and wrong, and sacrifice for others, in the case of these 2 works in particular.

It may be that the overt fictiveness of sf&f acts to make such fictions “safer” by making them more distant from the reader’s reality. Yet looking at how sf&f fans actually process the works they read, I’m not convinced. Characters like Frodo and Harry Potter are as real to many readers as the people they meet in classes or the workplace every day. Which, yeah, may be a problem in itself, but it’s certainly *not* a problem that speaks to not wanting to see truth in fiction.

More interesting, in my view, is the question of why some readers prefer to read stories that don’t take place in a real-world setting. There is, I think, a profound critique of modern life underlying sf&f as a whole — all of whose readers, in my experience, display some alienation from modern culture. There are, I think, some potential connections to Mormonism here (including the fact that our worldview encourages thinking of current culture as less of a given). Nonetheless, I see this as not at all the same as the desire of some readers to avoid challenging material in fiction — or the suspicion of other readers toward fiction in general. Overall, I think that trying to develop a unified theory of Mormon reactions to fiction obscures more than it clarifies — although it does raise interesting questions.

This all rings true to me, Jonathan. What’s interesting to me is that given all of what you write above, there are Mormon readers (in fact, probably the vast majority of Mormon readers) who will read realistic fiction or SF&F or other genres, but who either have no interest in or actively distrust any work in their preferred genre that deals overtly with Mormonism.

You both raise excellent questions and deal with them in thought-provoking ways.

The people I know who don’t read fiction regard it as a waste of time. For me, fiction is essential work–and my desire comes into play no matter the genre.

When I was a child, I had a very difficult home/family life; I won’t go into the details. I read a lot, and time and time again, I found myself drawn to fiction that portrayed successful families in action: the works of Alcott, L’Engle, Jane Langton, and Margaret Sidney, among others. I read them over and over again, dissecting what made those relationships work, because I was desperate for stability and love in my own life and wanted to know how to create it for myself. Twenty-five happily married years later, I believe my search was fruitful.

These days, an important part of my fiction reading is a similar wrestle. The fiction I love best displays in its characters the qualities I lack: the wisdom of Atticus Finch; the grit of Sam Gamgee or Scarlett O’Hara; the integrity of Esther Summerson; the faith of Alyosha Karamazov; the vision of Danny Torrance. I see the desirability of these traits. I see how they work and how they fail. I find ways to relate and change. Fiction enhances my empathy for both the good and the bad within people.

But of course, I preach to the choir.

.

Is that Danny Torrance the child or Danny Torrance the adult?