In their 1979 book, The Mormon Experience, Leonard Arrington and Davis Bitton identify Vardis Fisher as “perhaps the most important writer of Mormon background” in the history of American letters. “The next generation,” they suggest, “will be in a better position to evaluate him.”[i]

The next generation has now spoken, and it is not good news for Fisher’s legacy. In 1979, he had a small chance of ending up one of those writers that people call “important.” He was still studied occasionally in graduate seminars, and a handful of Ph.D. students had, within the decade, written dissertations about him. Though he had long been eclipsed by Faulkner, Hemingway, and Steinbeck, there was still some chance that he might end up somewhere in the vicinity of, say, Robert Penn Warren or Nelson Algren.

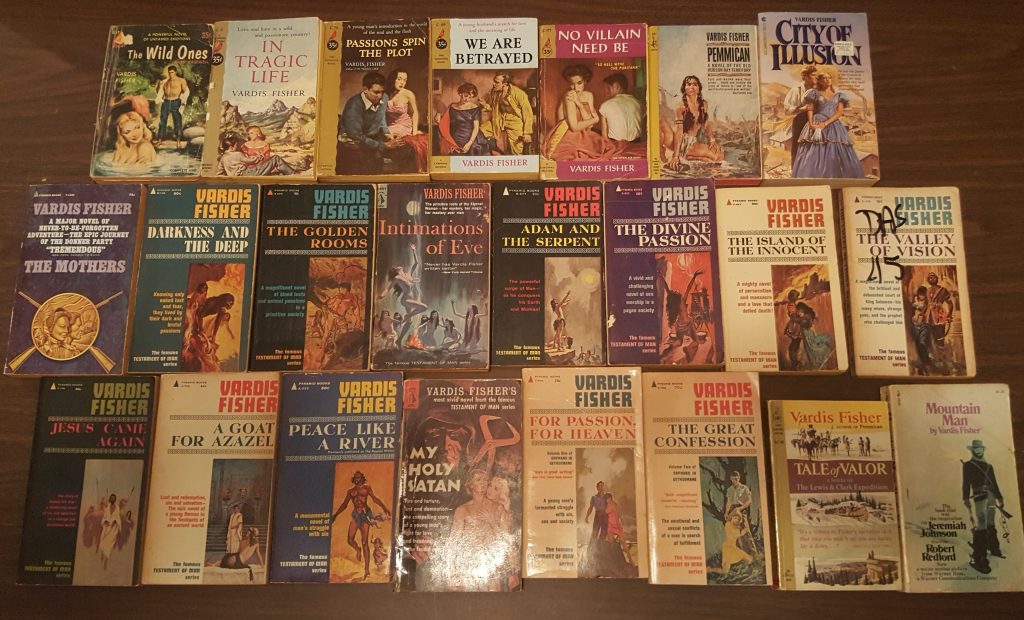

But it didn’t happen. Fisher’s books became more and more obscure, and the books that he was most famous for (Mountain Man, City of Illusion) were not the books that once formed the basis of his critical reputation. . And his widow, Opel Laurel Holmes, so vehemently objected to Arrington and Bitton’s characterization of Fisher as a “Mormon writer,” that she wrote a letter to then LDS-church president Spencer W. Kimball demanding that he direct the scholars to retract the libel.

Perhaps the great irony of Fisher’s literary afterlife, then, is that Mormon scholars are just about the only people still paying attention to him. And if there is ever a revival of scholarly interest in Vardis Fisher, it will be the Mormons who bring it about—not because he was Mormon in any kind of religious sense, but because he was a major Western writer who grappled with his Mormon heritage in much of his published work. As I once wrote in another context, “Vardis Fisher was a religious unbeliever; of this there can be little doubt. But Mormonism was the religion that he didn’t believe in.”

Mormon scholars and literary critics, I believe, would do well not to entirely forget about Vardis Fisher. His best work remains as powerful as any of the regional literature produced in the early 20th century. And most of this work intersects in significant ways with Fisher’s Mormon heritage. Below, I would like to give a brief description of Fisher’s work with some attention to how it might be of interest to the academic study of Mormon literature. My description will be divided into three categories that account for all but one of his published works of fiction.[ii]

The Antelope Novels

Toilers of the Hills (1928)

Dark Bridwell (pb The Wild Ones; 1931)

In Tragic Life (1932)

Passions Spin the Plot (1934)

We Are Betrayed (1935)

No Villain Need Be (1936)

April: A Fable of Love (1937)

“The Legend of Red Hair”; “The Scarecrow”; “

Charivari”; “The Mother”; “The Storm”; “Joe Burt’s Wife”;

“Laughter”–Stories collected in Love and Death (1959)

When Vardis Fisher became a writer, the rural Idaho back country that he grew up in provided his first subjects. His early novels and stories were set in “Antelope Hills”—a unified fictional storyworld, much like William Falkner’s Yoknapatawpha or Thomas Hardy’s Wessex. These novels share characters, locations, and families as they represent the turn-of-the century settlers who tried to eek a living out of a hostile landscape. Much of Vardis Fisher’s early critical acclaim was based on these Antelope novels, which were part of a much larger movement of regional naturalism in American literature.

And Mormonism was an important part of this region, though not the sort of Mormonism that we normally think of. As Dale Morgan wrote in his seminal 1942 essay “Mormon Storytellers,” Fisher’s early Mormon characters are “are the legitimate offspring of the Mormons who saw glories in the sky and praised God for a latter-day Prophet, but Dock Hunter [the protagonist of Toilers of the Hills] is the product of the interaction of Mormon society with the desert environment.”[iii] These characters are ruthlessly pragmatic and intensely focused on the world at hand—thinking of God only occasionally and not always with affection.

Four of these novels— In Tragic Life, Passions Spin the Plot, We Are Betrayed, and No Villain Need Be—constitute the “tetralogy,” Fisher’s fictional autobiography modeled on the work of his friend, Thomas Wolfe. These novels, especially In Tragic Life, show his early embrace of his parents’ Mormonism, his rejection of all religions soon after his Mormon baptism at the age of 19, and his struggle to make a family with his devout Mormon wife–who ends up committing suicide as a result of his infidelity. When he wrote these novels, nothing of the kind had ever been set in the Mormon communities of the West.

The Western Americana Novels

Children of God (1939)

City of Illusion (1941)

The Mothers: An American Saga of Courage (1943)

Pemmican: A Novel of the Hudson’s Bay Company (1956)

Tale of Valor (1960)

Mountain Man (1965)

Fisher himself did not think highly of the novels of this second group, but his publishers did. They were his bestsellers—and the basis of nearly all of the income that he earned in his life. The final novel, Mountain Man, became his bestselling work ever when it was made into the movie Jeremiah Johnson by Sydney Pollack and Robert Redford.

These novels dealt with some of the most famous stories of the American West, including the Donner Party (The Mothers), the Lewis and Clark Expedition (Tale of Valor), and the Mormon migration from Nauvoo to the Great Basin–which forms the basis of Children of God. This is the novel that made Fisher both famous and financially secure. It won the prestigious Harper publication prize, which came with a cash award of $7,500 (about $130,000 in 2016), and became one of the bestselling novels of 1939.

Children of God managed to offend both Mormons and anti-Mormons. Mormons found its portrayals of Joseph Smith and Brigham Young to be blasphemous, and anti-Mormons were upset by Fisher’s basically positive portrayal of the Saints—something that had been almost absent in historical fiction until that time. Fisher’s novel immediately became a standard reference about Mormonism for most of the country, and Fisher never wrote about Mormon history again, largely because he did not want to be cast as a “Mormon writer.”

The Testament of Man

Darkness and the Deep (1943)

The Golden Rooms (1944)

Intimations of Eve (1946)

Adam and the Serpent (1947)

The Divine Passion (1948)

The Valley of Vision (1951)

The Island of the Innocent (1952)

Jesus Came Again: A Parable (1956)

A Goat for Azazel (1956)

Peace Like a River (1957)

My Holy Satan (1958)

Orphans in Gethsemane (1960)

Had Fisher spent his career writing Western Americana, he would likely have died a wealthy man. Had he spent his time writing naturalistic regional fiction, he could have been as critically successful as Faulkner or Steinbeck. But after publishing Children of God, he resolved to pursue what he considered to be a much more important project. For the next 20 years, he spent the bulk of his time and energy writing a twelve-volume series tracing the intellectual, moral, spiritual, and sexual history of the human race from the Australopithecus (about 1.4 million years ago) to the late 1950s. Collectively, he called this series The Testament of Man.

In these books, Fisher traces a specific thread of civilization—the thread that eventually produced Vardis Fisher. The first two novels take place in early pre-history among people struggling to make sense of their world without even the benefit of language. The next two books take place in an early Semitic culture that moved from a matriarchy to a patriarchy by ridding of itself of all female deity figures. This culture produced the Jews (books 5-7) and the Christians books 8-11). The final book on the series, Orphans in Gethsemane (pb two vols: The Great Confession and For Passion, for Heaven), is a re-writing of the tetralogy, of Fisher’s own fictional autobiography.

Except for the final volume, none of these books has anything to do with Mormonism per se, but nearly all of them deal with figures who are simultaneously inside and outside of a religious community. In my opinion (and I wrote about this in Dialogue recently, but you will have to pay $1.99 to read it until the end of the year) we can learn more about Fisher’s relationship to Mormonism by reading these books carefully than by reading any of his books that specifically deal with Mormon themes.

But should we? Given Fisher’s low standing with the literary establishment (and the fact that all of his books are out of print and almost impossible to find), should we even bother to keep studying him at all?

I think that we should. For two reasons: first, the process of canon building has not occurred in Mormon literature the way that it should, and without an understanding of our own canon, we cannot understand how our own literature got to be the way that it is. The second reason is even more fundamental: Vardis Fisher brought a powerful mind and an artist’s vision to questions about Mormonism, religion, community, and identity that many of us are still asking today. He spent his life struggling with these questions in ways that can also make our answers better. And that is what literature is supposed to do.

[i] Arrington, Leonard J, and Davis Bitton. The Mormon Experience: A History of the Latter-Day Saints. New York: Vintage Books, 1980. P. 330.

[ii] The outlier is Forgive Us Our Virtues, a loose collection of satirical portraits that Fisher published in 1938

[iii] Morgan’s Mormon Storytellers first appeared in the Fall 1942 issue of Rocky Mountain Review. Cited from Eugene England and Lavina Fielding Anderson, eds., Tending the Garden (Salt Lake City: Signature, 1996), p. 8.

.

As someone meaning to give him a chance but will only do it if he gets a recommendation for one of the slimmer volumes, what would you suggest?

Also, which book doesn’t show up within these categories?

The best book to start with (assuming you don’t want to tackle the 600+ page CHILDREN OF GOD) is the short comic novel, APRIL. It is compelling, affirming, and a quick read. Fisher himself considered it his best early book. The novel not accounted for in my taxonomy is a 1938 book called FORGIVE US OUR VIRTUES, which is a strange collection of satirical sketches that really doesn’t fit very well with anything else that he wrote.

Vardis’s Testament of Man series sounds (without having read any of it) rather like the sort of overly ambitious project that can turn into a kind of literary white whale for an author. How was it received during his lifetime? How well do the volumes in this series work as stories, independent of the conceptual superstructure?

Jonathan, that is precisely what happened. The series was not well received. The first two volumes got a lot of love from the critics, but not much in the way of sales. Publishers tried to persuade Fisher back to the Western Historical fiction that they could sell, but he kept plugging away on it. His first publisher dropped him after Volume 5. He fled to Caxton, the Idaho Press that had always supported him before, who published Volume 6 but refused to publish Volume 7 (a naturalistic telling of the life of Jesus) fearing public backlash. It took him three years to find another publisher (Alan Swallow) who would complete the series. This is what his biographer, Tim Woodward, says about the impact of the series:

“For its author, the TESTAMENT’s toll was beyond calculating. It would cost him twenty of his most productive years, a close friend and publisher, and any hope of maintaining the reputation he briefly enjoyed as one of the nation’s up and coming novelists. People told him he was wasting his time on scholarly books that delved deeply into the past when he could have been writing novels that would have secured his reputation as an artist. Few who knew him doubted his ability to write `successful’ books, but he wasn’t writing the Testament for the best-seller lists. He was convinced he was writing it for the ages.”

As stories, the novels are uneven. The first two are quite good as exa ples of novels trying to get into the minds of people in pre-linguistic cultures. The next three are (IMO) good stories, but they make an argument for a matriarchal, pre-Semitic culture that is no longer seen as a viable model by anthropologists. I think that the Sixth book (the Valley of Vision, which is the story of King Solomon, is the best of the series.

The second half is, to be frank, awful. He becomes more and more of a propagandist as he tackles Christianity, and some of the novels (most seriously _A Goat for Azazel_ don’t even really tell a story–they just dump a lot of historical data and make anthropological and theological arguments. (That said, it is one of the most interesting books in the series; it just isn’t a very good novel). My own judgment is that the series is a failure, but it is a noble failure and an illustrative one. We can learn a lot by watching a reasonably talented novelist take on a project that exceeds his ability but stretches him farther than staying within his competence ever could have.

“Ah but man’s reach should exceed his grasp, or what’s a heaven for?” (Browning)

Since you seem genuinely interested in Vardis Fisher I feel compelled to say something, though I can’t help but sounding like a crank. I came across one of his books because of interest in his Mormon novel by a family member. When I read the book I was shocked to find all of the signs that he was a follower of A.R. Orage–who brought the Gurdjieff Work to the USA in 1925. There are many, many literary giants of the modern period that followed Orage and the number of novels written in the mode that Fisher followed. I compare him to Frank Yerby who was as prolific but managed to write in a more popular style while also doing the strange things that you will find in their books. I did not think Fisher could be an Oragean until I found that he was a close friend of Thomas Wolfe and under the direction of Maxwell Perkins. Both of those persons followed Orage and Perkins was a key publisher of their writings. If you examine Jesus Came Again you will find that a few pages into section 3 where it says “But the Sicarii…” there is a printing error. These errors abound in all of the books but are of different types. they indicate that there is a code in use. In that book fisher refers to the Orageans as Essenes and what he is saying is that they are using the CPUSA as a mask. I am just now writing a book on this but i show how to read this sort of book in my book, Oragean Modernism. this movement is unknown due to many factors but once you realize that Fisher is one of them you can see what he is doing rather easily. It’s really not very interesting since he just inserts the names Orage, Ouspensky, and Gurdjieff over and over on nearly every page and also favors the numbers 3 7/8 and 9 (7and 8 being interchangeable) but it explains why he is such a strange and determined writer –and seems not to be religious while writing in a mode that at the same time is not without reverence for something because it is esoteric–and it places him into a context of other writers who were writing a great deal in some cases. Faulkner was another vastly prolific and odd one, I only discovered recently. Read Pylon if you want to see it more clearly that he is esoteric.

That’s very interesting. And perhaps not surprising that one of the “lost generation” of Mormon writers would be interested in that type of mysticism.

I don’t believe a word of what you wrote. I was a follower of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky and Orage, etc., and nowhere was Vardis Fisher ever mentioned in any of the esoteric literature. I don’t think Vardis Fisher would have taken well to leadership or being directed — at all. You got a burr up your butt and you’re sticking to it but your claims are nonsense. Most of Orage’s work occurred in England. And where the Gurdjieff influence existed, it occurred in New York, London and Paris. This is so far from the realm of Vardis Fisher territory, you don’t know the man at all.

And Orage and Gurdjieff were both Christians, i.e., believers, however esoteric was their “theology.” Vardis Fisher was an out-and-out atheist. Vardis Fiisher may have read Orage’s books, may even have read Gurdjieff’s or Ouspensky’s writings — for research. There’s no evidence of any esoteric influence by the Fourth Way system at all on Vardis’s writing or thinking.