Consider this poem:

Bunk-House Poetics 1

……… A poem should not mean/ But be.

……..……..….. Archibald MacLeish

The way we read our fellow-poets is likely

how they’re reading us—meaning that all

too often we’re writing the same poem,

trying to get readers to experience some

“feeling” we think they should all be “feeling.”

Why not get some emotional distance by

writing in the third-person? Why don’t we

tell our stories, or make statements about

interesting subjects, without constantly

repeating “I,” “I,” as we go along?

Poets and students of verse are generally

not very interested in a poet’s “feelings”;

but like all readers they want to experience

strong feelings of their own—based on what

poets have to say and how they say it.

What poets say must be about things more

important than mere sentiment. The way

to profound emotion runs through a mind

enchanted by ideas and matchless artistry.

Poems must beautifully mean—to be.[i]

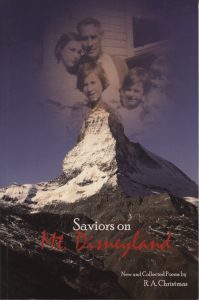

The poem is from Saviors on Mt. Disneyland : new and collected poems by R. A. Christmas. As the number indicates, there are more of these poems: 10, in fact. With Bob’s permission, I am going to examine the poems, and what they mean to be. What they aim for is a very plain-spoken introduction to contemporary poetry. What you can make of them is good poetry, if you accept them as a guide to your own writing.

In these poems Christmas discusses much of what I have been working towards in this blog — in ten short lessons suitable for discussion even in a bunk-house full of working men. I don’t know whether Christmas had so-called “cowboy poetry” in mind, but, as you will see, these lessons in poetic procedure apply even to that self-promoting genre. I am pursuing his instructions because (a) they’re in verse, and (b) they present a sterling defense of both free and bound verse.

Take the above poem. I attend an open mike night most Thursdays at the Enliten Bakery in Provo. I generally read three or four poems. Many of the readers there perform one or two poems, often reading from their phones, “trying to get readers to experience some/ ‘feeling’ we think they should all be ‘feeling.’” Substitute hearers for readers and you have a fairly accurate picture of that open mike. “The way/ to profound emotion runs through a mind/ enchanted by ideas and matchless artistry” is Christmas’s counter to all that feeling.

Now with that in mind, look at this next poem:

Bunk-House Poetics 2

The house was quiet, and the world was calm.

……… ……… Wallace Stevens

Why do poets persist in thinking that poetry

is “self-expression,” pretty words planted

in artsy phrases, and the like? Walt Whitman’s

partly to blame for this, with his obsessive

celebration of himself in line after line.

Whitman’s marvelous, of course. But few

can match his mastery of the long-phrase.

We get too carried-away, our effusions seem

forced, have what’s been called a “barded”

tone that even Walt warned himself about.

What we don’t want a poet to be implying is

“Look at me! I’m writing a poem! Wow!

It’s beautiful, complicated and important,

because, well, it’s poetry. See the fancy

words! Share my astounding feelings!”

You can avoid this trap by calming down,

and resisting any “show” of vocabulary.

Most great poems are written in what

has long been called “the plain-style,”

everyday words, in striking order.[ii]

Christmas does not let up in his attack on feeling and feelings here, but he adds to it the further idea that one should write poems in “the plain-style” — which is where his epigraph comes in, from Wallace Stevens. In fact, for purposes of this post, it’s worth reading Stevens’s entire poem:

The House Was Quiet and The World Was Calm

The house was quiet and the world was calm.

The reader became the book; and summer night

Was like the conscious being of the book.

The house was quiet and the world was calm.

The words were spoken as if there was no book,

Except that the reader leaned above the page,

Wanted to lean, wanted much most to be

The scholar to whom his book is true, to whom

The summer night is like a perfection of thought.

The house was quiet because it had to be.

The quiet was part of the meaning, part of the mind:

The access of perfection to the page.

And the world was calm. The truth in a calm world,

In which there is no other meaning, itself

Is calm, itself is summer and night, itself

Is the reader leaning late and reading there.[iii]

This poem is an excellent example of “everyday words, in striking order.” One of the most striking elements is that phrase “wanted much most to be,” which I had carried about in my head long before I could identify the source. Now, I have a penchant in my own poems for the “show of vocabulary” Christmas mentions. I find myself moving more and more, as I consider these Bunk-House Poetics, in the direction he prescribes. I will close with the third of these exercises in exercising restraint:

Bunk-House Poetics 3

……… They cannot look out far.

……… They cannot look in deep.

……… But when was that ever a bar

……… To any watch they keep?

……… ……… Robert Frost

It’s not fancy words—it’s word order.

Powerful syntax is the mark of great verse.

Poets don’t write words, lines—they write

sentences in metrical (or other) forms; and

sentences are distinguished by syntax.

Grammar isn’t “rules”—it’s a description

of verbal possibilities. Originality within

the limits of grammar is style; the lack of it,

triteness. Outside grammar lies incoherence,

language that refers only to itself.

There’s something about meaningful and

creative syntax at the limits of grammar that

entrances the mind—that is perceived as

beautiful no matter how common the words.

Elizabethans loved these “strong-lines.”

Which of the following lines—think you—

did Ben Jonson write: “Man may securely

sin, but safely never,” or “Man may sin

securely, but never safely”? Come now,

how can the answer not be obvious?[iv]

Here, Christmas adopts his professorial voice, to disabuse the bunk-mates of the idea that any plain statement is poetry. When he writes “Grammar isn’t ‘rules’—it’s a description / of verbal possibilities” he is summarizing a whole generation’s worth of linguistics, but the heart of the poem is in the line “creative syntax at the limits of grammar” (which you saw at work in “The House Was Quiet and The World Was Calm”). This is what makes a line, a conceit, a poem, memorable.

These three instances of Bunk-House Poetics are really good guides to reading poems, as well as to writing them, and you will get closer to truth with them as your guide than any other guide you might choose, especially since Vergil is no longer giving tours of Hell.

That’s my post for this day. I have but one thing left to say: you have to buy Saviors on Mt. Disneyland online, but not, through, say, Amazon. You have to buy it here: www.lulu.com/spotlight/rachristmas. It is self-published. Give this poet some encouragement and order a copy of this book today. Now. Before you finish reading this post.

But what’s that I hear you say? We’re already at the end of the post? Then order soon.

Your turn.

____________________

[i] Saviors on Mt. Disneyland : New and Collected Poems / by R. A. Christmas; p. 25

[ii] Ibid., p. 28

[iii] The Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens (Alfred A. Knopf, 1954), as posted by Poetry Foundation, accessed at https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/57607/the-house-was-quiet-and-the-world-was-calm on 22 December 2017.

[iv] Op. cit., p. 53.

.

The most immediately striking thing about these poems is just how plain they are. Almost prose.

Exactly. In the next installment, I will allow Bob to explain that, in Bunk-House Poetics 4-7.