The observant among you have noticed that Bob Christmas hyphenated Bunk-House in the titles of his “Bunk-House Poetics,” which indicates that the hyphenated phrase is an adjectival nominal modifying a noun, in this case Poetics. Given how careful Christmas is with his phrasing and punctuation, if a hyphen were left out, the phrase could mean “House Poetics that are Bunk” — no! I’d better debunk that one right now. Christmas punctuates better than that.

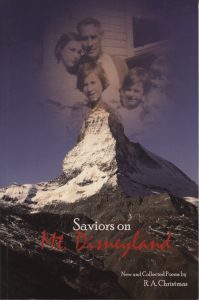

If this were a post-structuralist blog, I could accuse Christmas of being an old white guy, but again, in his poems, he has taken care of that. He has very carefully written that tough truth throughout Saviors on Mt. Disneyland, without conceding, though, that his identity makes him ineligible for poetic stature. Now, however, in “Bunk-House Poetics 8,” he starts down a different slippery slope: quantity versus quality.

Bunk-House Poetics 8

………..Write little; do it well.

………..Your knowledge will be such,

………..At last, as to dispel

………..What moves you overmuch.

………..………..Yvor Winters, “To a Young Poet”

All poets (including this one) tend to overwrite.

We’re very verbal, excitable—we have so

much to say, about our own lives especially;

and we’re just dying to share it with others.

Sadly, this is the downfall of most poets.

Do your readers a favor and write one-page

poems eighty—no, ninety—percent of the time.

Avoid writing multi-page poems that read

like somebody’s confessional diary (ouch!).

Keep your lines and your poems short.

You’re not Chaucer, or Pope; you’re writing

the English Lyric, a form that enabled Hardy,

Shakespeare—many others—to achieve near

perfection in verse. And believe it or not,

you can do the same—if you pay attention.

Robert Frost could have written poems about

his ruinous family life—and Stevens about

his work in insurance. But they didn’t.

Because great poetry, while it is about us,

can seldom be great if it’s only about us.[i]

And here Christmas addresses the poetry that his poetics are written to help shape. Not for the first time in this sequence of poems, but head-on. He has been circling the subject throughout these poems, but now, for the first time, he meets it on its own ground — the question of quality. In the lines he borrows from Yvor Winters, he urges a near-fatal restraint, one born of a certain and necessary modesty: “You’re not Chaucer, or Pope” he says — not only because they are better writers than you, but because you are writing lyric poems, not epics.

And this is true in my case, as in his. I have written one epic, about Joseph Smith, and am writing another, both in Anglo-Saxon verse. But most of what I write is short lyric poetry. So “Bunk-House Poetics 8” speaks to my weakness, as well as to my ambition, “Because great poetry, while it is about us,/ can seldom be great if it’s only about us.” The “us” he speaks of are the poets he is writing these poetics for. And there are a lot more Mormon poets than there used to be. Good ones, too.

So now Christmas brings in the element of Mormon thought into his poetics, obliquely, as is his wont, but unmistakably, in number nine:

Bunk-House Poetics 9

……..And the Lord said unto me: These two facts do exist, that

……..there are two spirits, one being more intelligent than the

……..other; there shall be another more intelligent than they;

……..I am the Lord thy God, I am more intelligent than they all.

………..………..………..……….. Abraham 3:19

It’s hard for English majors to write great poetry,

because, for the most part, they’re taught

literary history, not literary criticism—or, if they’re

taught the latter, it’s usually by professors

who seldom—or never—write verse.

In these relativistic and poetically correct times

it’s difficult—even dangerous—for students

to champion certain styles or poets, when those

poets are out of favor with professors in power.

If you’re Christian, or logical, look out!

If you want to write great verse, you must think

clearly about your craft. You must be brave

enough to take the unfashionable position

that certain poets write and think better than

others, and make them your mentors.

Objectively, Wallace Stevens is likely a better

poet than Robert Frost—it’s a close call. But

Ben Jonson is surely better than them both.

Alas, if we could objectively evaluate every

poem ever written, one would top the list.[ii]

Spoken like a true Mormon. You might imagine you hear in that “alas” a sigh of resignation. No. What you hear is a thrill of propriety — Christmas is willing to leave the judging to one who is more intelligent than they all. He is ready to return to writing his short, simple, declarative sentences.

That readiness I attribute to the subject of his final essay, number ten. It is easy to delude yourself that you are writing out of great knowledge, or wisdom, or pain, or experience — that you have something to pass on. But here is what Christmas has to say about that:

Bunk-House Poetics 10

……..And it is not always face,

…….Clothes, or fortune, gives the grace;

…….Or the feature, or the youth.

…….But the language and the truth,

…….With the ardor and the passion,

…….Gives the lover weight and fashion.

……..……….Ben Jonson, “His excuse for loving”

Writing poetry is always, always, about love—

even if it’s only the love of writing it. And

even if you think these poems on poetics are

total bunk, you can still learn to write good

verse if you’re passionate enough about it.

Desire (love), Imitation (of the best poets),

and Practice (not hundreds of poems—more

like a hundred hours on the right poem)—

these are the keys to writing great poetry.

Genius is the result of “infinite pains.”

Sorry, but you’ll be lucky if in your life you

write five fine poems. Not only that, but

for the most part your stuff will be unread,

misunderstood, and unappreciated. Writing

poems is solitary (read lonely) activity.

Why people do it is a mystery you’ll have to

explain to yourself. Partly, it’s our passion

for a greater awareness of what it means to be

alive—an awareness that comes in a special

way through beautiful, insightful verse.[iii]

I will not bother to notice that Christmas actually says that “even if you think these poems on poetics are/ total bunk, you can still learn to write good/ verse” because the focus of this final lesson is on passion, on desire, on taking infinite pains to write well. Christmas has actually written several fine poems, and one way he does this is by writing with a certain wry humor. You might think that humor and passion are at odds with each other, that it would go better with you to choose one or the other, especially since Freud said that all humor is tendentious, whereas love is all about cherishing, not harming, the other.

But take a look at one of his poems, still about writing poems, still about this love of his life:

Let’s Get This Straight

Jesus stooped down and with his

finger wrote on the ground . . .

John 8:6

His first wife paid for his Ph.D. After

the divorce, she earned one on her own,

and raised their kids without complaint.

When he and his second wife separated,

she worked his job when he was ill,

and gave it back when he recovered.

His third had cancer—and him. She raised

five of his, four of her own, and wished

he’d get religious and stop scribbling.

Hypocrite readers, drop your stones. There’s

lots of sides to these one-sided stories.

They’re no more adulterated than you are.

Faint-hearts, fuddy-duddies—begone!

When imperfect poets write on the ground,

there’s no way fingers won’t get dirty.[iv]

This is truly a poem about love. Above the poet’s love for three different women, and their love for him, love that results in goodness all around. It’s a religious poem as well, showing the love as it functions in imperfect hearts. There’s a humorous twist on the story of Jesus and the woman taken in adultery, and it ties two different kinds of loves together: that of Jesus in forgiving the woman, that of the poet not only seeking forgiveness, but finding in the love of his wives a forgiveness. He does not shine by comparison with Jesus. That is the saving grace in this ironic self-appraisal. But he does not intend to. He includes himself among the imperfect poets of this life. They are the ones with the dirty fingers.

But hold on, I hear you say: isn’t that all of you?

Your turn [but don’t bother to point out that, with this post, I’m all caught up].

[i] Saviors on Mt. Disneyland : New and Collected Poems / by R. A. Christmas; p. 106.

[ii] Ibid., p. 126.

[iii] Ibid., p. 155.

[iv] Ibid., p. 2.

One thought