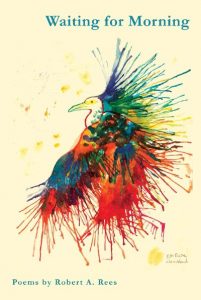

Robert A. Rees, one of the doyens of Mormon Studies, will have his first poetry collection, Waiting for Morning, published by Zarahemla Books later this month. He provided us with this essay about his history with poetry.

How I Came to Poetry

How I Came to Poetry

by Robert A. Rees

It is difficult

to get the news from poems

yet men [and women] die miserably every day

for lack

of what is found there.

–William Carlos William

All that can be done with words is soon told.

–Robert Frost

I came to poetry late, or rather it came to me that way. There was no poetry, literal or figurative, in my childhood or my adolescence. My home and culture were what H.L. Menken would have called “The Sahara of the Bozart.” There was no possibility I would have gotten Mencken’s pun until I minored in French at BYU. The beaux arts, which ultimately came to define both my personal and professional life as well as have a profound influence on my spiritual life, would more likely to have been mocked in my home, if responded to at all. Until I went to college. I don’t remember having read a single poem, including in my high school English classes, although it is more than probable that I did.

It was in Professor Robert K. Thomas’s “Introduction to Literature” course at Brigham Young University during my sophomore year that I first had any inkling that words could do what they do in poems, which, as Marianne Moore claims, is where we find “imaginary gardens with real toads in them.” In Thomas’s class, I recognized something was going on with rhythm and rhyme, with imagery and metaphor and with symbol and sense, but as intrigued as I was by the sound of words, by all that musicality of meaning, by the way words danced on the page and in my mind, I wasn’t able to make sense of it. In fact, I felt that those who understood poetry, including my classmates, had been born or blessed with some special gift, a sort of charmed intelligence that allowed them to decipher those strange rhythms, runes and rhymes, the syntax of heart and mind found in lines and stanzas. So, in class I kept my mouth shut and listened. But Bob or “Brother Thomas” as we called him, had a way of awakening even someone like me to the wonders of the imaginative play of language. He was, of all the teachers I have been blessed to have, the most gifted. In fact, it was in his class that I not only came alive intellectually and imaginatively but where I decided I wanted to do what he did—become a teacher of literature.

In retrospect, he may have sensed something in me of which I was scarcely aware. Perhaps it was a rude, untutored hunger for beauty; an impulse to find meaning wherever I could find it; or a quest to unravel sense and sound in whatever I saw and read. His class sent me excitedly to Shakespeare, Chaucer, Milton (all taught by the legendary Parley A. Christensen), the Modern Novel, Eighteenth-Century Literature, the American Renaissance, and many other wonderlands of literature. In reading poets from these periods, I had what is called a shock of recognition, something akin to what Emily Dickinson expressed upon reading a book of poetry: “If I read a book and it makes my whole body so cold no fire can warm me I know that is poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry. These are the only ways I know it. Is there any other way?”

In spite of all the poetry I read in such courses, when I went to graduate school, I still had little confidence as to what poetry really was or certainty that I could understand, let alone write about and teach it. I still was of the conviction that whatever it took to really grasp poetry, I didn’t have it. It certainly never occurred to me that I could write a poem that was really a poem. To arrive at such a point reminds me of what the American poet J.V. Cunningham wrote to one of his students, “You have learned not only what to say/But how the saying must be said.” I hadn’t yet learned either.

I can’t pinpoint the turning point in my poetic life. Perhaps it was in studying modern poetry and the freedom from form that blank and free verse offered. Having graduate courses in which I had to study poems so closely that they seemed to become part of my consciousness helped, but it wasn’t until I started teaching at UCLA and had to know poems well enough to say something intelligent about them—and answer hard questions from bright undergraduates–that I really began to have a cognitive as well as an intuitive sense of what poetry is and how it works. This confirms Robert Frost’s observation that poetry is “a thought-felt thing.” I came to see that my problem was that I was approaching poetry as one or the other rather than the two working together. I now understand that the heart and the head are both essential not only in understanding but also in teaching poetry.

I can’t pinpoint the turning point in my poetic life. Perhaps it was in studying modern poetry and the freedom from form that blank and free verse offered. Having graduate courses in which I had to study poems so closely that they seemed to become part of my consciousness helped, but it wasn’t until I started teaching at UCLA and had to know poems well enough to say something intelligent about them—and answer hard questions from bright undergraduates–that I really began to have a cognitive as well as an intuitive sense of what poetry is and how it works. This confirms Robert Frost’s observation that poetry is “a thought-felt thing.” I came to see that my problem was that I was approaching poetry as one or the other rather than the two working together. I now understand that the heart and the head are both essential not only in understanding but also in teaching poetry.

The writing of poetry, however, is a very different thing, as is feeling that any poem is worthy of publication. In his essay, “The Figure a Poem Makes,” Frost uses a striking metaphor to explain the process: “Like a piece of ice on a hot stove the poem must ride on its own melting.” Frost also says the process, “begins in delight and ends in wisdom, . . . ends in a clarification of life—not necessarily a great clarification, such as sects and cults are founded on, but in a momentary stay against confusion.” I understood that, for often I found myself reading poetry as a way of seeking clarity and coherence, of ordering my feelings, of seeking “a momentary stay against confusion.” It was when I stopped trying so hard to write poetry, stopped thinking about it so much and took the risk of letting a poem find its own way that I began to write something approaching poetry. As I wrote in a poem to my late wife, Ruth, who complained that I wrote poems for others and on all kinds of subjects but never for or about her:

I know only this: some day

when I’m walking along a street somewhere,

not even thinking about it or perhaps

thinking about being with you on that island

off Green Bay, a poem will come,

as poems sometimes do, and when it does,

it will be for you.

I was forty-five when my first poem was published and at times years have passed between publications. That I have written poems worthy of publication in reputable journals, magazines and books is a wonder to me. That I have written enough to be published in this collection is a sort of miracle.

I have been blessed to hear some poets read their poetry live. The first was Carl Sandburg when I was an undergraduate at BYU. A number of notable poets came to read at the University of Wisconsin when I was in graduate school, but the one I remember most vividly was Robert Frost. Teaching at UCLA afforded many other such hearings, including Seamus Heaney reading “Personal Helicon” with the last lines: “ . . . I rhyme / To see myself, to set the darkness echoing.”

When I was at UCLA in the eighties, I was blessed to lead two groups of American writers to China and to bring two groups of Chinese writers to America. Out of that experience I was privileged to become friends with poets like Gary Snyder, Allen Ginsburg, Alice Fulton and Charles Wright, among others. Traveling through China with such poets helped me to see how they saw and I watched and listened. Some of the poems from those encounters are in Waiting for Morning, including the following:

Echoes of the Han Shan Bell

(with Gary Snyder and Allen Ginsburg,

Suzhou, China, 30 October 1984)

Gary Snyder gives a copy of

Cold Mountain Poems to the old priest

at Han Shan temple:

“This book has finally

come home.”

The bell sound in his heart,

he reads Zhang Ji at Feng Bridge

and writes a poem.

Sitting on Maple Bridge,

Allen hears it too

and writes his own.

On the train back to Shanghai

Masa recalls learning Zhang Ji

in a country school outside Kyoto

and remembers every line.

Every poet is aware of his or her indebtedness to other poets and to any muse who inspires. In addition to the poets listed above, the poets living and dead to whom I am indebted are too numerous to mention, but I will mention several poet-friends who have been particularly influential, by encouragement, example or specific suggestions for shaping some of the poems in Waiting for Morning–Mary Bradford, Robert Christmas and, especially, Clifton Jolley, whose careful ear, observant eye and brutal honesty helped make some of these poems better than I could have made them myself.

After declaring that the figure a poem makes begins in delight and ends in wisdom, Robert Frost says, “The figure is the same for love.” Indeed it is. As a Mormon, I believe that love is eternal and, therefore, happy thought, that poetry is as well. I can’t imagine eternity without poetry. Following Frost, one could hope that poetry begins in love and, instead of ending in wisdom, lights our way, worlds without end.

————————————————

Robert A. Rees, Ph.D., is Visiting Professor and Director of Mormon Studies at Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley. He has taught at UCLA, UC Santa Cruz, UC Berkeley and the University of Wisconsin and Vytautas Magnus University in Kaunas, Lithuania. In addition to teaching and scholarship, Rees has served as Assistant Dean of Fine Arts and Director of Continuing Education in the Arts and Humanities at UCLA where he was also Director of Studies for the UCLA-Cambridge Program and the UCLA Royal College of Art and Royal College of Music Programs in London. Long active in Interfaith work, Rees served as President of the Religious Studies Conference at UC Santa Cruz and, more recently, on the board of the Marin Interfaith Council. He is the co-founder and current Vice-President of the Liahona Children’s Foundation, a humanitarian organization that addresses children’s malnutrition in the developing world.

Robert A. Rees, Ph.D., is Visiting Professor and Director of Mormon Studies at Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley. He has taught at UCLA, UC Santa Cruz, UC Berkeley and the University of Wisconsin and Vytautas Magnus University in Kaunas, Lithuania. In addition to teaching and scholarship, Rees has served as Assistant Dean of Fine Arts and Director of Continuing Education in the Arts and Humanities at UCLA where he was also Director of Studies for the UCLA-Cambridge Program and the UCLA Royal College of Art and Royal College of Music Programs in London. Long active in Interfaith work, Rees served as President of the Religious Studies Conference at UC Santa Cruz and, more recently, on the board of the Marin Interfaith Council. He is the co-founder and current Vice-President of the Liahona Children’s Foundation, a humanitarian organization that addresses children’s malnutrition in the developing world.

Rees has published widely on Mormon and Religious Studies as well as on politics, culture, literature, education, the arts and LGBT studies. He was the Editor of Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought from 1971 to 1976. He is the editor or co-editor of Proving Contraries: A Collection of Writings in Honor of Eugene England (2005), A Readers’ Book of Mormon (2008), Why I Stay: The Challenge of Discipleship for Contemporary Mormons (2011), The Emerson Society Quarterly: Index of the First Decade (Transcendental Books, 1966), Fifteen American Authors Before 1900: Bibliographic Essays on Research and Criticism (University of Wisconsin Press, 1971, 1984), Washington Irving’s The Adventures of Captain Bonneville (Twayne, 1977), and Guide to the American Short Story (Coast Community College, 1982).

Rees is the author of No More Strangers and Foreigners: A Mormon Christian Response to Homosexuality (Family Fellowship, 1998) and Supportive Families, Healthy Children: Helping Latter-day Saint Families with Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Children (2012). He has just completed a second volume of Why I Stay as well as a collection of articles on LGBT Issues and Mormonism. Rees has served as a bishop, high councilor, and member of the Baltic States Mission Presidency.

Rees has long been involved in Mormon literature. In Autumn 1969 he co-edited “Mormonism and Literature”, a special issue of Dialogue. He was one of the early members of the Association for Mormon Letters, and helped pick the very first AML Award winners in 1978. He has received three awards for the personal essay by the Eugene England Foundation and received the 1981 AML Poetry Award for his poem “Gilead”. His collection of poems, Waiting for Morning, will be published later this month by Zarahemla Books.

Praise for Waiting for Morning

“The wrecked and wretched of the world . . . speak holy words,” and Bob Rees has the sagacity to hear them and render their holiness in poetry. What Eugene England did for the personal essay, Rees does for poetry—dedicating its shapes to the sacred work of witness, Mormon con- science, and presence. These pages remember the mother he lost, the wife he survived, and the war-afflicted and imprisoned in places near and far away. They are suffused with the tireless industry, expansive vision and pragmatic elegance of the Mormon people. I am grateful.—Joanna Brooks, co-editor, Mormon Feminism: Essential Writings, and author, The Book of Mormon Girl

In his poetry Bob Rees plumbs the depths of his responsive soul while painting the landscapes of his courageous life. He has mastered the vocabulary of poesy in an evocative way. Whoever reads his work will enter a life well lived and generously shared.—Mary Bradford, poet, author of the collection Purple

Robert Rees’s Waiting for Morning pays homage to all human experience—life to death—reading mysteries in “the calligraphy of seagrass,” finding solace in the “systolic and diastolic pulse of creation,” expressing infinities in the “the runed and ruined language of the world.” His poems reflect a keen observer’s open heart, seeing pain in beauty and beauty in pain, and finding, in each, minute moments of truth. The poignancy of “A Mirror for Josephine Miles” elicits tears of gratitude for human courage and brilliance, while “Universe” sees in a week-old grandson a universe “that will expand infinitely.”—Michael R. Collings World Horror Con Grand Master and Multiple Bram Stoker Award finalist for poetry

There is much to admire in Bob Rees‘s collection, especially (for me) the first two sections, “Experience” and “Abandoned.” And Clifton Jolley’s introduction is indispensable for understanding Bob’s poetry in the context of American literary history and criticism. The overall value of Waiting for Morning comes from Bob’s skill as a poet: his deep and broad experience as a humanitarian and educator; his overcoming of a traumatic childhood; and, finally, and most importantly, his lifelong determination to place the Restored Gospel of Jesus Christ first in his heart and mind, no matter what. Waiting for Morning is a worthy addition to the many intellectual and artistic services Robert A. Rees has provided to thoughtful Mormons throughout his life.—R. A. Christmas, author of seven books of poetry

Stirred to fullness and passion by life’s abundance, Whitman sang, “I will go to the bank by the wood and become undisguised and naked, / I am mad for it to be in contact with me.” His “it,” of course, is the world, beat- ing and breathing all around him. Bob Rees exhibits a similar madness in Waiting for Morning: a madness to be in contact with life in its many manifes- tations, to hold it close, and to be nourished by that closeness. Stripped of pretension, Rees’s poems lay bare a mind exposed to his physical, cultural, and spiritual environments. They show him in celebration and grief, deep longing and joy, but always basking in words.—Tyler Chadwick is the editor of Fire in the Pasture: 21st Century Mormon Poets, and co-editor of the forthcoming Dove Song: Heavenly Mother in Mormon Poetry.

I have missed the magic you create with words!