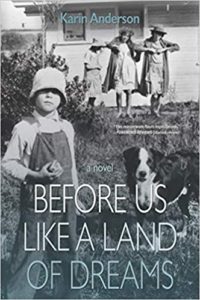

Karin Anderson, a Professor of English at Utah Valley University, introduces her novel Before Us Like a Land of Dreams.

Karin Anderson, a Professor of English at Utah Valley University, introduces her novel Before Us Like a Land of Dreams.

In her 1972 throwdown, Adrienne Rich declares: “Re-vision—the act of looking back, of seeing with fresh eyes, of entering an old text from a new critical direction—is for us more than a chapter in cultural history: it is an act of survival. Until we can understand the assumptions in which we are drenched we cannot know ourselves.”

Rich’s “we” meant certain women at the threshold of second-wave feminism, but her strategy applies more universally: we might manage to walk ourselves into an authentic, nonredundant meaning of future as we reconfigure fragments of our first making.

I wrote Before Us Like a Land of Dreams as simultaneous claim and renunciation. I removed my name from the records of my ancestral religion years ago, but sometimes I have to remind ya’ll: apostasy is not amnesia. My core perceptions were shaped by six generations of Mormon ideologies: obliterating that large fact would mean erasing myself, including far too much of what (and whom) I love. And so, as a PostMormon writer, I work to reinvent and re-portray. I don’t tell The Truth; I pry out disparate truths. I don’t build; I remodel.

My secular children can’t fully absorb how their lives have been shaped by their Latter Day Saint heritage. And they don’t have to. However, they reside – and plant gardens, and hike, and ski, and ramble, and sleep in sand and snow – in the strained gorgeous American West because certain ancestors were mysteriously touched by the story of a boy, an angel, and a continent. Our immitigable genetic whiteness grates against their hybrid sensibilities. My children probably understand, at least to a point, that their mother stocks food, plants vegetables and fruit trees on her little suburban lot, and lines up gas cans, propane, generators, tents and jugs of water in her garage because she was raised to shelter her crew through an apocalypse. But their own sense of impending global catastrophe arises from data rather than prophecy, with more deadly implications than the faith that once promised to save my kind at the expense of the unchosen.

My children will never quite know what it means to feel happily, securely enclosed within generations of family, living and dead. That’s a good and bad thing: it made for delightfully smug self-affirmation for me as a child, evolving into chafing constraint as I grasped toward alliances with other tribes, other ways of knowing. Leaving the Mormon fold has in many ways turned me into a stranger in a familiar (and beloved) land. The chasm between in and out is real, a heimlich blight in my view but just another crag in the home scenery for my kids.

Writing Before Us Like a Land of Dreams was an overdue project of mapping some ineffaceable yet always contingent meanings of family and home. “Before,” in my appropriation of Matthew Arnold’s “Dover Beach,” points back to what precedes us, yes, but also toward the time and terrain that spread open as we approach. The five stories that comprise this “novel” stack up like overlays – each story palimpsests the others over the same Utah, Arizona, and Idaho sites. It doesn’t really matter whether you read them in order; the point is cyclical accumulation, rupture, and revision.

Most of the stories are set between 1860 and 1960, but all are insistently filtered through a 21st century bias. The book is often catalogued as “Historical Fiction” but it tends to disappoint genre fans. My research was six-years copious, but I wasn’t locating discrete facts in order to produce a seamless sensation of verity. I’m interested in those attractive gaps between the facts. And so the ancestors are real, templated over a Book of Remembrance Family Group Sheet, but obstreperous fabrication wraps the branches.

The first story, “Homing,” chronicles a 21st century road trip toward an obscure gravesite in Arizona borderlands, materializing into a time-warp encounter with vanished family. The remaining stories are implicitly structured as interviews within small galaxies of dead people: “Great White Chief” speculates on the origins of an incorrigible family temper, fanned to high heat in 1860s Mantua, Utah and passed down through my paternal grandfather. “Grassman of the Year” reconstructs the surprising social and cultural stew of first-generation Anglo homesteaders in Idaho’s Snake River Valley, inhabited by my mother’s taciturn paternal German Lutherans. “Devil’s Gate” is a kind of séance, betraying my paternal grandmother’s urgent insistence that I should “just leave that story be.” I follow flickers of an old myth of British nobility, the brutal ideological corrosions of frontier life, and the reverberating impacts of insanity and suicide.

I call “Tooele Valley Threnody” an invocation, even though it’s the closing story. This is partly because the plot begins earliest, in New England just beyond the American Revolution. Because my mother’s maternal people all died young from congenital heart disease, this family line bequeathed no firsthand tales. My access was pure internet glean: I wondered why a prestigious, educated Eastern family would uproot property, prestige, and custom to answer to the Mormon cause. Strangely, these people seemed more accessible to me personally than any other characters I tried to commune with – maybe because no one lives now to contradict my impressions. The book ends with the Emersonian “testimony” of Festus Sprague, a young man bound for Utah and a violent death: witness to the colliding trajectories of ideological dream and the blunt forces of destiny.

I’ve brokered a few recurring questions from readers since the book’s May 2019 release, so I’ll briefly touch on them here:

Since so much of this book is fiction, why didn’t you change the names of the characters instead of telling lies about real people? Fair question. I did change some names for narrative clarity and alias cover, but I make so much noise about my authorial unreliability that it becomes the very point. All we can do is invent the people who came before us. The facts, sparse as Nevada silver, reveal very little about the bewildered characters they mark. Interpretation is always speculative, but it’s where the human meanings reside. If my version of any story sparks another, and another and another? Good.

How am I supposed to know which parts of the stories are true and which parts are made up? Easy: as soon as you decide it’s fiction, it is. But you can also have fun tracking fascinating confirmations on the internet, and make of them what you wish. I was stunned at how many hand-me-down opacities opened fleeting transparencies as I reconstructed historical clues. It was alarmingly easy to find facts that upended everything I thought I knew. I learned to pay close attention to the don’t look over there details of adamant morality tales; they leaked like kitchen colanders. I learned to open cauterized bleeds, yank hidden headgates, and follow clotted meandering flows.

If you leave, then you should shut up. What gives you the right to go on about people and doctrines you say you’ve relinquished? Yucky question. They’re mine as much as anyone’s. And my children’s. And they belong to many of my students who have been cut out of the communal will, against their will.

Why can’t you accept that “Mormon literature” is an academic joke? Infuriating question. I will never suggest to any of my students that their experience is off limits for creative or intellectual content. I’ve seen a remarkable rising generation of writers who come from very real, marvelously unexamined places and cultures. A university education is about collision, salvage, and reinvention, just like the best literature it spawns. Mormon experience under the pressures of tough academic challenge is dynamite. Just watch.

What’s next? I’m curating and co-editing (with the brilliant poet Danielle Dubrasky) an already stunning collection of environmental writing from believing and nonbelieving inheritors of Mormon traditions. Blossom as the Cliffrose: Mormon Legacies and the Beckoning Wild will be released by Torrey House Press in summer of 2021. Also, I’m in deepening research mode for a novel about coming of age in Utah Valley in the very still but strangely turbulent 1970s. Track me down if you’re willing to tell me a story.

Karin Anderson is a Professor of English at Utah Valley University where she focuses on creative writing, lit theory, wilderness and environmental writing, LGBTQ lit, contemporary narrative genres, and honor legacies. Her work has appeared in Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, Quarter After Eight, Western Humanities Review, Sunstone, Saranac Review, American Literary Review, and Fiddleback. She has produced the novels Breach (Fiddleblack Press, 2013) and Before Us Like a Land of Dreams (Torrey House Press, 2019). She has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize, a finalist in Quarter After Eight, and awarded “Best Short Story by a Utah Author.” Karin holds degrees from Utah State University, Brigham Young University, and the University of Utah; she hails from the Great Basin.

Karin Anderson is a Professor of English at Utah Valley University where she focuses on creative writing, lit theory, wilderness and environmental writing, LGBTQ lit, contemporary narrative genres, and honor legacies. Her work has appeared in Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, Quarter After Eight, Western Humanities Review, Sunstone, Saranac Review, American Literary Review, and Fiddleback. She has produced the novels Breach (Fiddleblack Press, 2013) and Before Us Like a Land of Dreams (Torrey House Press, 2019). She has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize, a finalist in Quarter After Eight, and awarded “Best Short Story by a Utah Author.” Karin holds degrees from Utah State University, Brigham Young University, and the University of Utah; she hails from the Great Basin.

Here are two reviews of Before Us Like a Land of Dreams:

Library Journal (Starred): In this autobiographical first novel from Pushcart Prize winner Anderson, the narrator is 54 and in the chokehold of a personal crisis when she undertakes a road trip from Utah to Safford, AZ, a small town near the Mexico border where her father was born. She feels a kinship with her grandmother, who was forced to leave behind the grave of a stillborn baby when the family moved, and at the cemetery imagines herself as a time traveler conversing with mourners gathered by the baby’s graveside. Soon she’s being guided by her ancestors, particularly her grandfather’s older sister, Iola, who appears in the passenger seat beside her, talking about the early times in Utah and how the neighboring Shoshone were kinder to the settlers than the settlers were toward one another. As other voices take over, we learn about the narrator’s siblings; her difficult father; their large, fractured Mormon family; and the part their long-dead Norwegian, Danish, and German ancestors played in building the vast American plains. VERDICT: Anderson’s fictionalized journey through time was prompted by her mother’s declining health, her son’s hospitalization, rampant wildfires plaguing the region, and a beloved country severely divided. A work of universal appeal.

Kirkus: This resonant novel is told in a multitude of voices, forming a family saga that is both a revisionist history of Latter-day Saint settlement in the American West and a personal journey.

Anderson draws upon her own heritage for this sweeping story. It begins with a long chapter narrated by a woman in her 50s, a mother and professor who cannot fathom where her life goes next: “I want my mostly-grown kids to get on with their own lovely ludicrous lives and leave me to salvage mine.…I no longer know who to be.” In search of herself, she leaves “Whitepeople Central, Utah,” for a small Arizona town where an aunt who died in infancy is buried. There she has the first of several intense visions of her ancestors, revelations of their lives that form the novel’s subsequent chapters. As the book’s genealogy chart shows, Anderson will lead readers through two centuries and half a dozen generations of a family that eventually joined the Latter-day Saint migration to the West. Their lives are filled with great hardship and loss, foolhardiness and danger—at one point, grown men leave an 8-year-old boy to guard cattle on a mountaintop amid lethal raids by the Shoshone—and moments of wonder and love. Anderson does not shy away from the often bloodstained relationship between the Latter-day Saints and the Indigenous tribes they displaced or the religion’s other forms of bigotry. She strips the romanticism from traditional notions of how the West was won: “I’ve spent a lot of time, post-Emersonian that I am, trying to figure out why it is that living in beautiful scenery so often turns human beings into violent fanatics. It’s not what Wordsworth predicted, or Thoreau or Whitman or Brigham Young. Hawthorne maybe.” In powerful prose, she lets a chorus of voices tell their own often surprising, sometimes heartbreaking stories.

People from several generations of one woman’s family gain vividly individual presence, recounting their lives in the American West as it moves from wilderness to modernity.