Review

———-

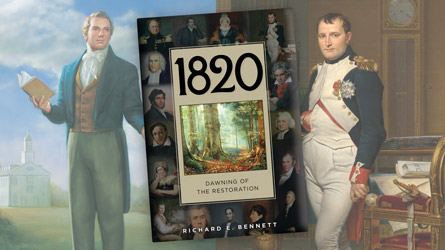

Title: 1820: Dawning of the Restoration

Author: Richard E Bennett

Publisher: BYU Religious Studies Center

Genre: History

Year: 2020

Number of Pages: 517

Binding: Hardcover

ISBN-13: 978-1944394943

Price: 31.99

Reviewed by William Winkler for the Association for Mormon Letters

Many Latter-day Saints (of all denominations) who adhere to the orthodox narrative have wondered what was it about the world that changed in the early 1800s, that made God decide the time was right for the revelation of gospel truths that had been concealed for centuries. This is certainly the line I was expecting a book written by a BYU religion professor and published in house would take, and indeed, Bennett admits in his introduction this was originally his plan. I was therefore delighted to find that in the 20 years he spent compiling this series of biographies he came to the conclusion that this providentialist “fairy-tale” proved excessively reductive, and he resolved to let the lives of the dozen biggest news-makers of the early 19th century tell their own story.

For the most part, Bennett succeeds quite well. Hints of his original project remain. For example, in the first chapter on Napoleon, he expands unnecessarily on the “pro-family” (meaning anti-divorce) articles of the Napoleonic code in what feels like a strained attempt to bridge to contemporary Salt Lake church political preoccupations. And, though all the chapters are necessarily brief biographical sketches of 25-50 pages about men who have been the subject of multiple books, Bennett takes time to dwell on their religious lives even when evidence is skimpy or largely irrelevant to their accomplishments (e.g., the Prussian explorer and natural historian Humboldt in Chapter 12). In my reading, I felt that such investigations and/or speculations would have been best either left out or made the primary subject of the work. With the exception of these minor lapses, the biographies are lucid, well-researched, and otherwise unmotivated by an attempt to make these men seem either morally better or worse than they really were.

The subjects range from the political (Napoleon, Tsar Alexander I, George IV, Henry Clay, and Simon Bolivar), to the artistic (Beethoven, Gericault, Coleridge), to the scientific (Champollion, Humboldt), with two more gestalt-y chapters on the major trans-Atlantic social movements of abolition and missionary societies. The book ends with a retelling of the events around Joseph Smith’s first vision that, though somewhat dismissive of scholarship that questions the influence of the Second Great Awakening, is otherwise both broad and balanced, making no attempt at hagiographically setting Smith apart from his culture, but rather remarkably showing the many ways in which his religious though was a natural outgrowth of it. Bennett structures the chapter so that he can mention the multiple first vision accounts without attempting to resolve their contradictions, and discusses religious excitement as a widespread and common phenomenon without the confusion of which specific revival triggered Smith’s prayer. I was particularly impressed by his retelling of several stories of New Englanders experiencing visions and forgiveness of sins after meditating on a scripture in nature, or praying in a grove of trees, activities other devotional writers have tended to grant to Smith as a monopoly.

The best writing in 1820 is the chapter on Gericault, particularly his analysis of “The Raft of the Medusa”. Though Bennett acknowledges it had an overtly anti-government message, he convincingly argues that Gericault intended his audience to see a soteriological message as well. From the pale bodies lying at the base of a cross made by the mast and yard-arm, the “series of diagonals moving up from the foreground toward the sky captures the climactic moment of both hope and despair” as the raft emerges from darkness into light. This is where Bennett’s method works best, where he is able to nod at the significance of 1820 to Mormons without claiming divine intervention directly on their behalf.

The only quibble I had with 1820’s balance was in his discussion of cultural imperialism in Chapter 10 about the growth of Bible and Missionary Societies. Though Bennett spends a paragraph allowing that these groups overzealously did incalculable damage to local cultural identities and knowledge, the remainder of the chapter is hortatory of the remarkable statistics these groups achieved in terms of copies printed, translations performed, and countries reached. The discussion makes it clear that the costs of expanding Christianity are, in Bennett’s view, minimal compared to its benefits. While this is certainly better than discussing all other denominations as rivals to the Latter-day Saints, it still feels like an us-vs-them retelling of an often-cruel conquest (with “us” being ecumenical Christianity).

While this book adds little to the scholarship of its 12 subjects, or even to devotional literature about how God prepared the world for the restoration, it is an accurate, eminently readable, fair, and broad introduction the zeit that saw such an outpouring of the holy geist. Bennett is to be commended for broadening his own view of world history through this project, and it will serve as gentle reminder to what can sometimes be a provincial religion that the world is much bigger and more interesting than just what we read about in Sunday School.