Title: Women and Mormonism

Editors: Kate Holbrook and Matthew Bowman

Publisher: The University of Utah Press

Genre: Essay collection

Year of Publication: 2016

Number of Pages: 354

Binding: Paper

ISBN13: 978-1-60781-4771

Price: $34.95

Reviewed by Julie J. Nichols for the Association for Mormon Letters

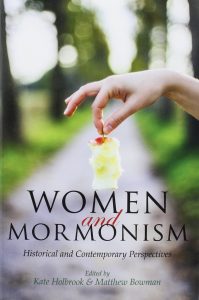

About a month ago I sat under an awning in the garden patio of a local bookstore listening to a book talk by Kate Holbrook and Matthew Bowman about the development and contents of the volume under review here. Its theme is agency: how Mormon women have experienced and expressed their agency, and “the diverse ways [they] have understood the relationship between their faith and their personal agency” (from the back cover). One of the fun moments of the book talk came at the beginning, when Holbrook asked what the audience thought of the book cover. It shows a woman’s hand holding out an all-but-consumed apple core. “It represents Eve throwing away the stigma of eating the apple,” somebody said. “It’s a coy invitation,” somebody else suggested. “We think it shows that Eve relished the whole thing,” Holbrook said. “She gobbled it up, for the sake of agency.” We all applauded.

I had read about half the book before attending the book talk. I’d been especially drawn to essays like Carine Decoo-Vanwelkenhuysen’s “Mormon Women in Europe: A Look at Gender Norms” (213) As a non-Utah-native, I found that my own attitudes about marriage, education, and work outside the home resemble more closely those of the women surveyed by Decoo-Vanwelkenhuysen, who are comfortable with and take for granted their and their daughters’ roles in public life, than those of many Utah women choosing domestic life over professional development because they think the Lord commands it. I listened to the talk about the book as a whole with interest and pleasure.

During the question and answer period, a member of the audience, a non-LDS professor of history, challenged Holbrook and Bowman about their use of the word “agency.” It’s inaccurate to say that Mormon women have 100% agency, she said. The system (the Church, polygamy, priesthood) limits their agency in ways the book doesn’t acknowledge. Holbrook and Bowman parried with predictably Mormon definitions and defenses: Mormon women have done remarkable things to shape the history of their church, cities, and nation. They’ve used their agency in strong ways that historians have often slighted. It was a lively but mildly awkward exchange, as neither the questioner nor the book’s editors seemed satisfied with the others’ understanding.

Later I emailed the professor for further explanation. Because she left town shortly thereafter and I didn’t ask permission to reprint her reply verbatim, I will paraphrase it here.

According to this historian, “agency,” as Mormons use the word, is a theological term—and one so universal as to be practically meaningless, since anything can be seen as an act of agency. (I must insert here that, in my experience and probably in yours, this is frequently the case: “well, s/he has his/her agency and I can’t deny them that…” “well, s/he chose that path and must take the consequences…” “well, you have your agency, do whatever you want, I can’t stop you even though I don’t like it.”)

But this is not how the social sciences use the term. In recent years, scholars of such institutions as slavery tend not to focus on resistance (an aspect of “agency”) because such a focus minimizes the horror of the institution/system itself. Perhaps slaves did resist. Perhaps Mormon women did, and do, make creative and independent choices from within the system. But the inequality, injustice, and other sometimes miserable consequences of the institutions/systems themselves must be addressed as such. The adherence to principles of obedience that lead Mormons to praise strong, accomplished women can, but shouldn’t, blind us to the cultural and historical bases of policies and strictures that are not, in my correspondent’s view, absolute truths.

This response to the book’s central theme naturally had an impact on my reading of the rest of the collection. *Women and Mormonism* consists of the proceedings of a 2012 conference arranged by Holbrook and Bowman, entitled “Women and the LDS Church: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives.” That was before Ordain Women, but Holbrook and Bowman’s thoughtful introduction addresses both the complexities of the term “agency” and the ways that OW “drew significant attention to the relationship between gender and priesthood authority” (9). They conclude that “[to] hold to one metric [of official authority in measuring women’s agency] both ignores women’s exercise of agency to act within institutional parameters, and neglects possibilities for more radical conceptions…outside of [those] parameters” (ibid).

In other words, “agency” can be expressed in faith communities in multiple ways. Some of those ways look like resistance and change. Some may look like, but are not necessarily, blind obedience; conscious obedience can be a valid choice too. That stance is familiar to us all—which is why Decoo-Vanwelkenhuysen’s essay felt so refreshing to me. For European Mormon women, “obedience” doesn’t mean marrying young and forgoing education and career. It still means giving intelligent service, but there are ways to do that appropriate to culture that are not necessarily the ways prescribed in Utah. So this volume explores such options, and for that reason stimulates and revitalizes thinking about women in the Church.

There are some similarities between this volume and Patrick Q. Mason’s *Directions for Mormon Studies,* which I reviewed last week. Both are outcomes of conferences seeking to identify issues and point toward future studies. Both volumes are divided into sets of essays focused on methodology, history, social science approaches, and personal narrative. Both embrace scholarly lenses to ask questions about how and why Mormonism has evolved over time and across localities.

Some of the issues treated in *Women and Mormonism* include polygamy, material culture, Mother in Heaven, Jane James (the 19th-century African American convert who sought to be adopted by Joseph Smith), Mormon women in the Pacific and in the Sierra Leone, sexual agency, and the professionalization of reform. Mary Farrell Bednarowski’s essay on “Intersecting Paths in the Journeys of Mormon and Roman Catholic Feminists” illuminates similarities between LDS and Catholic activists:

“[Our] theological concerns go well beyond priesthood, and sometimes I wonder whether too much emphasis on achieving priesthood masks the extent to which we care about many other issues—authority, scripture, vitality of doctrine, authenticity, and responsiveness to changing times—all of which are directly related to the future well-being of our communities” (314).

Some Latter-day Saints might respond to this with the perennial reference to prophetic directives—God will give us new information when he’s ready. We don’t need to worry about the future—we’re God’s church, after all; He’ll take care of us. But Bednarowski’s naming of these issues illuminates genuine concerns for Mormon women from an angle unfettered by that perhaps too-easy fallback. Doing so can, I think, open new possibilities for strong and effective action by Mormon women so inclined.

P. Jane Hafen’s “My Book of Mormon Story” similarly offers a strong and necessary angle of vision. As a Native American, she experiences racism in many aspects of Book of Mormon interpretation. In her calling as Primary chorister she refuses to play the Primary song “Book of Mormon Stories” because its rhythms and colonizing language promote inappropriate stereotypes. Her story is honest and unflinching and should cause readers to examine attitudes they may have left unquestioned.

These and the other essays in *Women and Mormonism* foster further discussion. (I can see book groups like the one I belong to having a heyday with this volume.) This collection belongs in the library of every scholar of women’s history, religious history, or women’s religious history. Frankly, it belongs in the library of every educated Mormon woman. Imagine what might happen if it were the basis of Relief Society lessons! These are issues we need to be discussing actively and acting on together, as agents in our own milieu, in each other’s service, and in the evolution of the Church. Our history and our future demand this of us. Our sisters’, our daughters’, and our own lives within the Church may very well depend on it.