Review

Review

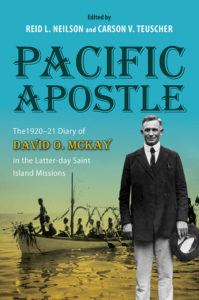

Title: Pacific Apostle: The 1920-21 Diary of David O. McKay in the Latter-day Saint Island Missions

Editors: Reid Neilson and Carson Teuscher

Publisher: University of Illinois Press

Genre: Documentary History

Year Published: 2020

Number of Pages: 314

Binding: Cloth, Paper, eBook

ISBN: Cloth, 978-0-252-04285-0; Paper, 978-0-252-08467-6; eBook, 978-0-252-05171-5

Price: Cloth – $110.00, Paper – $27.95, Ebook – $14.95

Reviewed by Andrew Hamilton for the Association of Mormon Letters

It’s 2020, members of the various branches of the church started by Joseph Smith are celebrating the 200th anniversary of the year that he declared that he had his “First Vision”. The 200th anniversary of Smith’s founding of the Church of Christ in 1830 is ten years away. The Joseph Smith Papers Project and other publishers are releasing many high-quality biographies, narrative histories, and documentary history volumes. With so much going on and with so many choices of Restoration history books to read and study, you might be asking yourself, “With all of these options, why would I choose to study David O. McKay’s diary of his 1920-21 mission to the Pacific? Can there really be any significance to this mission 100 years later?”

Reid Neilson and Carson Teuscher, the editors of Pacific Apostle, acknowledge this conundrum in their introduction to the volume. They concede that with two centuries of source material to work with, when writing and telling the history of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, “even the best scholars sift, coalesce, and synthesize their narratives” into “broad,” sometimes “oversimplified,” categories that can cause important moments in history to become “muddled.” One of those “muddled” moments is determining when the LDS Church truly began its “modern global expansion.” McKay’s 1920-21 mission dairies document a “pioneering endeavor to visit, observe, and fellowship with the Church’s expanding global constituency in the Pacific.” They also record over sixty-one thousand miles of travel and numerous meetings that would be “the basis of important initiatives taken by David O. McKay when he became president of the Church more than three decades later” (p. xliii).

Neilson and Teuscher continue and explain that McKay’s diaries are among the most important primary records in the LDS Church. They specifically state that these Pacific Mission diaries serve as a “time capsule” that preserves “snapshots of … travel, Pacific cultures and religious growth through missionary work (along with) candid observations of the cultural, political, economic, and social milieu of the period” (pp. xliv-xlv). They conclude their introduction by stating that these diaries contain an “eye-opening peek into the convoluted racial, cultural, religious, and social climates” of the time (p. xliv).

After studying Pacific Apostle, I heartily concur with Neilson and Teuscher. McKay’s Mission diaries as found in Pacific Apostle are a key record that document an important period in Mormonism’s transition from a Utah to a worldwide faith. They are a priceless window into the thoughts and learning process experienced by David O. McKay. They also give those who study them a view of Mormonism’s past as well as an important study of its present and a glimpse into its future. As I read the book, I really began to understand how David O. McKay is an important “bridge” between the past, present, and future of the LDS Church. I’ll comment more on how the diary entries demonstrate this later, but first I want to highlight how the supplementary material that Neilson and Teuscher include in the volume emphasizes McKay’s role in linking the LDS past and present.

Pacific Apostle includes numerous insightful footnotes and two appendixes. The second appendix is a biographical registry of all the missionaries serving in the missions that McKay visited on his tour. This registry gives the names, birth and death dates, and a few biographical facts on each of the roughly 300 missionaries that McKay met with. The dates in this section help to highlight that David O. McKay is an important bridge to Mormonism’s past and the present. When you examine the birth and death dates of the Pacific missionaries that McKay interacted with and influenced, you find that among the older missionaries there were some who were born in the 1860’s with the earliest being born in 1862, when the LDS Church was only 32 years old. Among the younger missionaries that McKay ministered to during this time, some lived well into the late 1990s with the last one passing away in 1998 when the Church was nearly 170 years old. Added to this information is a footnote on page 2 about McKay’s son Robert who was born just before McKay left on his Pacific Mission. Robert lived into this last decade, passing away in 2013. This means that David O. McKay and the events recorded in “Pacific Apostle” have a direct link to at least 151 of the 190 years of Mormon history. That position in time gives McKay, his experiences, ideas, and teachings suggest a more spread out impact than any other LDS leader.

The experiences that David O. McKay had that are documented in Pacific Apostle came about because Heber J. Grant and the leaders of the LDS Church were concerned with the growth and condition of the Church in the isles of the Pacific. So, in 1920, the forty-seven-year-old McKay was called, along with companion Hugh J. Cannon, to spend a year travelling the Pacific. They were to meet with the local Saints and missionaries, teach and support them, and learn about them and the condition of the Church in the lands that they visited and then report what they discovered. The reason why Pacific Apostle is SO important is that this mission proved to be a MAJOR learning experience for McKay that influenced the rest of his life, his teachings, and the decisions that he later made as LDS Church president.

McKay was born northeast of Ogden, Utah in the small mountain town of Huntsville, Utah. With the exception of a proselyting mission in England when he was a young man, up to 1920, McKay had spent his entire life and ministry among people who looked and sounded like he did. The mission documented in Pacific Apostle proved to be a major learning experience for McKay and the whole LDS Church. I’ll mention just a couple of the things that can be learned about McKay, his personality, and the lessons that he learned on his mission when reading Pacific Apostle.

McKay loved literature and he loved words. He may have been the most literate and well read of the LDS Church presidents. Even in his private writings his language is very descriptive. When describing his wife Emma Ray’s emotional state as he was preparing to leave on his mission McKay wrote:

“She reminded me of one of the pretty little geysers in Yellowstone – it would remain placid and peaceful for a while, but soon the forces, hidden and turbulent, would stir the surface of the water until it swelled, bubbled, and boiled over the rim until the pent-up forces were set free” (p. 2).

This is one example of the writing style and personality insights about McKay that can be found in the book.

Like anyone who spent the majority of their life among people who looked and thought just as he did, McKay struggled with opening his mind to new people and new experiences. In Pacific Apostle McKay, for the first time in his life, is spending a lot of time among other races and cultures. The racism and attitudes that McKay grew up with become very apparent as he describes the people he is meeting in his journal entries. But, and especially if you compare Pacific Apostle David O. McKay to the more mature Rise of Modern Mormonism: David O. McKay, you can see the growth and learning that happened to McKay on this mission. That said, you will read some disturbing entries in these records as McKay encounters new and different people. In early entries he frequently drops the term “Jap” and seems genuinely surprised that the Japanese people are “civilized.” When in China, he describes the people that he meets as “dirty creatures,” “hideous, loathsome creatures,” “not religious but superstitious,” and “beggarly.” When in Hawaii he expresses regret that the “pure-bred Hawaiian is being replaced by other more vigorous nations, particularly by the Japanese.” When in Fiji he decries that “there are no beautiful women here.” When travelling with Fijians on a boat he wrote that they were “as repulsive to me as the Polynesians are attractive.” It also becomes quickly apparent that McKay considers the USA far superior to all other countries and Mormons (a term he uses) to all other religious people, especially to members of the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints who he calls, “emissaries of his Satanic Majesty” and “a boil on the church body.”

While McKay writes some troubling things and notes, these references are largely confined to the first half of the book and his love and compassion for people becomes more apparent as time passes. It really is fascinating to witness McKay’s growth and learning curve as he meets and deals with new people and new situations. He even ends up spending several weeks in quarantine on a boat which ought to connect really well with readers and researchers in 2020! McKay’s expressions and reactions to his experiences early in the book are VERY provincial, but he grows as time passes, even if the growth is bumpy and rough for him. As McKay grows on his mission to a new worldview, so eventually does the LDS Church as McKay takes to heart and takes home what he has learned. Neilson and Teuscher are correct: McKay’s “pioneering endeavor to visit, observe, and fellowship with the Church’s expanding global constituency in the Pacific” thus truly does become “the basis of important initiatives taken by (him) when he became president of the Church more than three decades later” (p. xliii).

If you want to see the moment that Mormonism began to be a less isolated, closed off society, you will want to study “Pacific Apostle” and witness David O. McKay’s journey from small town apostle to being an experienced, more broad-minded leader.

Pacific Apostle is an important window into the life, teachings, influence, and growth of the most significant LDS leader of the twentieth century. It is an important resource for students and researchers of Mormon history. Neilson, Teuscher, and the University of Illinois Press have done an excellent job in preparing, footnoting, and contextualizing these invaluable records. At $110.00, the clothbound version is a little pricey for most individuals, but the paper version is a very affordable $27.95, and the eBook is an even better deal at $14.95. If you want to better understand David O. McKay and the experiences he had that informed the ideas that he had and the decisions that he made that lead to the development of modern Mormonism, you can now have access to those records for as low of a price as the cost of a couple of fast food value meals.