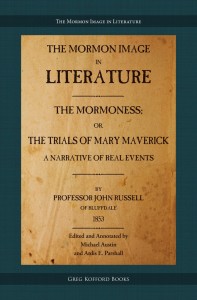

Title: The Mormoness; or, The Trials of Mary Maverick: A Narrative of Real Events

Author: John Russell, edited and annotated by Michael Austin and Ardis E. Parshall

Publisher: Greg Kofford Books

Genre: Historical literary fiction with critical apparatus

Year Published: 2016 [1853]

Published Number of Pages: xx + 93

Binding: Paperback

ISBN 13: 978-1-58958-507-2

Price: $12.95

Reviewed by Jenny Webb for the Association for Mormon Letters

When Kofford announced The Mormon Image in Literature series, I was intrigued. The series “reprints important literary works by and about Mormons—from the sensational anti-polygamy books and dime novels of the Civil War era to the first attempts of Mormon writers to craft a regional literature in their Great Basin kingdom.” While making such historical works available for today’s audience is of course an admirable task, the value of this material would then be enhanced by the inclusion of appropriate critical material, such as an introduction designed to situate the work and author within their cultural context along with various notes, annotations, and appendices. The promise of an “all-in-one” approach—the original text, along with a critical apparatus designed to aid the study of that text for both Mormon and non-Mormon readers—appeared smart, well-conceived, and useful.

Happily, the first book in this series, John Russell’s *The Mormons; or, The Trials of Mary Maverick,* provides a very good beginning to the series. The work that Michael Austin and Ardis E. Parshall have done in preparing useful critical material allows for any reader to approach and appreciate this text. Austin and Parshall give us a critical introduction to John Russell and his work, a handy timeline of Russell’s life, a bibliography of his works, the text of the novella, and then three thoughtful appendices: an article on Russell’s life written by his son, the full text of Russell’s 1841 letter to Thomas Gregg in which he defends the Mormons and criticizes the *Warsaw Signal*, and finally, a selection from Russell’s book *The Serpent Uncoiled*, in which we see Russell’s (much harsher) engagement with Universalism.

John Russell (1793–1863) lived his adult life in western Illinois where he became known as a thoughtful, open man who valued the tenets of American democracy, especially those pertaining to freedom. Russell wrote, taught, edited, and even preached (as a Baptist minister) throughout his life, advocating for causes such as tolerance, the abolition of slavery, and moral duty. His writings were well known and his opinion respected. His intersection with Mormonism occurred when he hosted Parley P. Pratt and William E. McLellin in 1833 at a time and place where they were receiving a fair amount of open hostility.

Later, when the Saints were forced to leave Missouri, many, including Pratt and Sidney Rigdon, found respite during their journey in the Russell home. It was at this time that Russell heard the story that would become the seed for *The Mormoness*: the account of the Merrick family and the murder of the father and 9-year-old son at Haunn’s Mill in front of the mother. Fifteen years later, Russell would take this story and rework it into a fictional account of a woman who converts to Mormonism for the sake of her husband, loses her husband and child to mob violence, and then spends the rest of her life industriously serving others, even to the point of saving the life of the man who murdered her family.

While the story is itself moving, Austin and Parshall’s historical contextualization makes it clear that Russell’s writing of *The Mormoness* was motivated by an ongoing sensibility for the political and ethical injustices the Mormons suffered in a country that, ostensibly, valued religious freedom. Austin and Parshall describe how Russell “insisted that American citizens had the right to be wrong in religious matters without being subjected to violent attacks” (xiii). I found Russell’s words in his letter to Thomas Gregg (a journalist associated with the *Warsaw Signal*) to be as pointedly relevant today as they were 175 years ago: “I think of Joe Smith just as you do, and I believe that a greater knave walks not the face of the earth, yet were I there I would defend his hearth-stone with my blood. Joe Smith is an American citizen, and shame on the people—all that can tamely stand by and see the sacred rights of any American cloven down” (81). Russell’s focus on the underlying political and ethical violations the Mormons endured is clear throughout the narrative of *The Mormoness,* which foregrounds the ways in which the heroine’s treatment endangers not only her own well being, but that of her country.

Interestingly, Russell’s project throughout *The Mormoness* can be characterized as a type of conversion: Mary Maverick, the Mormoness herself, undergoes various conversions, both religious and ethical, but it is ultimately Russell’s aim to convert *his readers* to an understanding of Mormons as Christians. As Austin and Parshall point out, this “is a book about Mormon identity. . . . By the end of Mary Maverick’s story, two facts are indisputable. First, the heroine is entirely Mormon. [. . .] At the same time, she is fully Christian. She has devoted her life to the care of others, with no regard for their economic situation or social position. And when confronted with her greatest enemy . . . she offers him not only compassion, but also forgiveness” (xv). Mary Maverick is introduced in terms that characterize her as a model of Christian industry and humility (6–9); throughout her life, she makes choices for the benefit and comfort of others (e.g., “She resolved to live usefully to others” [51], “the Mormoness devoted herself to the single purpose of doing good to others” [55], and, at her resolve to administer to Shawnee natives suffering a cholera outbreak, we see her in her commitments a Christ-like willingness to sacrifice her life for the benefit of others [57]).

By the end of the narrative, the heroine’s unwavering resolve to live a Christian life alongside the continual reinforcement of her religious identity through the title the narrator bestows upon her (“the Mormoness”) combine to create an effectively balanced portrayal of a Mormon character. Austin and Parshall are right to point out how unusual this effect is: “The portrayal of a Mormon character as an indisputable type of Christ was a truly remarkable thing at a time when nearly everything written about Mormons was either pro-Mormon propaganda or anti-Mormon invective” (xv).

This review scarcely scratches the surface of this fascinating text, but hopefully it does enough to provoke interest both in Kofford’s project in The Mormon Image in Literature series as well as the historical and literary intricacies of Russell’s work here specifically. My only reservations at this point have to do with a number of infelicitous minor errors that occur mainly in the critical apparatus. For example, the capitalization of the complete title of *The Mormoness* differs slightly between page xii, fn. 10 and page xv and the name of the original press appears in several iterations (xii, xviii, xix); there are errors in the application of italics (ix, xv, xvi); citation format is slightly inconsistent in the bibliography (xx); a name of a blog hosting a post cited is misremembered (xiii, fn. 11 continuation); pages are referenced out of order (xiv, fn. 13) and there are a few typos here and there (e.g., xvi “I” for “In”). And while these errors do not detract from the overall value of the series project nor the usefulness of this particular text, they do give me pause simply because at this historical remove the majority of readers will need to trust and rely upon the accuracy of the text. The hope, of course, is that as the series develops, such inaccuracies will be increasingly diminished.

Overall, however, the text is highly usable. The fresh transcription of the text itself is quite clean, and the inclusion of the original publication’s pagination enclosed in brackets throughout works quite well. Austin and Parshall’s historical contextualization and analysis provides an excellent entry for any interested in this text. And Russell’s narrative continues to resonate in an America that is still struggling in many ways to come to terms with the realities demanded by political and ethical ideals of equality, justice, and freedom. For Russell, the question may have been how to see the Christianity in a new and theologically disruptive religion; for us, the greater question of how to see the humanity of our neighbors makes this somewhat obscure, historical text surprisingly relevant today in multiple ways.

Highly recommended for those interested in the cultural history of America, the West, and Mormonism, as well as those who simply wish to reflect on the way questions of inclusion and exclusion inform our history and, potentially, our future.