Review

Review

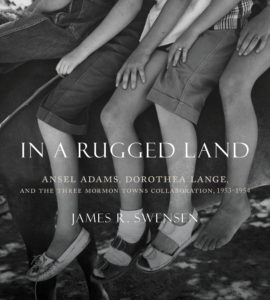

Title: In a Rugged Land : Ansel Adams, Dorothea Lange, and the Three Mormon Towns Collaboration, 1953-1954

Author: Swensen, James R.

Publisher: University of Utah Press

Genre: Art History

Year Published: 2018

Number of pages: 432

Binding: Paperback

Price: $34.95

Reviewed by Dennis Clark for the Association for Mormon Letters, Jan. 21, 2019

The “rugged land” referred to in the title is Washington County, Utah. The “three Mormon towns” are Gunlock, Toquerville and Saint George. And I am old enough to remember when Lange’s and Adams’s collaborative photo essay appeared in Life magazine on 6 September 1954. I was nine years old, and smart enough to know that both 45 and 54 add up to 9. But I lived in Provo, which was more of a city, near Utah Lake, which was fresh water, and Provo was just starting to build a sewage-treatment plant, to clean up Utah Lake (the clean-up took until 1967). As a city boy, I could have looked down my nine-year-old nose at these contemporaries, but perhaps they lived more cleanly than I.

Provo was a modern city, but Orem, Springville, Spanish Fork, American Fork, Lindon and Lehi, all towns, were also installing sewage-treatment plants, and Geneva Steel as well. I knew all that because I read the Daily Herald. And I could tell the difference between a city and a town. To judge from that photo essay, Gunlock was more of a burg, and Toquerville a village, and Saint George barely a town. But I recognized the people portrayed in the photographs reprinted in the magazine. To me, they were my people, they were life.

My only real gripe about this book, which is a large-format paperback, 10×8 inches, is that it reproduces the entire 10-page spread of the article in images that are about a quarter of a page, 4.25×3.125 inches, which makes it hard to read the text. And I am interested in reading the text because it caused a furor in the towns, especially Toquerville, that it sought to memorialize. The story of the publication of the article, called “Three Mormon Towns,” and its reception, takes up only the last 26 pages of text in this book. The notes, bibliography, image credits and index take up another 96 pages.

But the bulk of the book — the first 218 pages — tells the story of the project, the collaboration that produced that article: Dorothea Lange and her husband, the sociologist Paul S. Taylor, had the idea of following up on a sociological study of Gunlock by Edwin Banfield Jr., who had lived in the town with his family, and whom they had visited there in 1951. With them they brought Lange’s son by an earlier marriage, Daniel Dixon, whose father was Maynard Dixon, a painter.

Maynard Dixon and Dorothea Lange had lived in Utah twenty years earlier, in 1933, spending “four months that summer traveling from town to town and staying with Mormon families along the way” (7). Lange had returned to Utah a number of times since then, drawn to the place and its people, photographing them on assignment and at times for her own pleasure. One photograph from that 1933 trip with Dixon, captioned “Mary Ann Savage, Handcart Pioneer, Toquerville, Utah” was of a woman who had survived the ordeal of the Willie Handcart Company at the age of 6, in 1856, and later wed Levi Savage, one of the handcart companies’ captains, who “married her mother in 1858 and her and her younger sister, Adeline, ten years later” (12).

Paul Taylor, Lange’s husband in 1953, made a crucial contribution to the project: “He knew members of the Mormon hierarchy, including Apostle John A. Widtsoe. Widtsoe was the point of contact for many outsiders such as Taylor” (62-63). Lange and Taylor “knew from Banfield and from previous experience in the state that their project rested on gaining ‘active approval’ from the heirarchy” (62). But Widtsoe died “Months before their arrival” and they were “sent to the office of J. Reuben Clark, second counselor to President David O. McKay” (63). Clark had mixed feelings regarding publicity about the church, and Swensen explores them in depth. This is not the first place Swensen puts his training as an art historian to use, but it’s a fine example of historical work in the comparatively recent past. Swensen concludes that, when Lange and Taylor met with Clark, “The exact tenor and terms” of the permission granted to them are not known (68).

Ansel Adams thought he knew, and that supposition was to prove an irritant among the four of them. Adams “believed that he [Taylor] sold their project as a ‘sociological study’ with the possibility of an exhibition of their work. Taylor, Adams insisted, forgot to mention the fact that they were working on a story for Life” (68). Clark may have sensed any such omission, because he phoned the president of the Zion Park Stake to alert him to their coming. Thus, although they had some contacts, and permission to meet with local church leaders and make photographs, their work was under official scrutiny.

Daniel Dixon knew the south of Utah as well. Maynard Dixon had a home and studio in Mount Carmel. Daniel lived with Maynard “in the early forties” (68), and returned later to Mount Carmel “during the war” (69 — which could not have been much later). Lange, Taylor and Dixon drove into Gunlock on August 8th, and St. George on August 9th, where they checked into a motel run by Juanita Brooks and her husband. Lange had been making lists of pictures she wanted, and they spent two more days, while waiting for Adams, scouting the area. The only one lacking familiarity with Utah was Adams, who was finishing up a project in Tucson, Arizona. He joined them in St. George on August 10th.

The collaboration was hindered by ill health on Lange’s part, and by the hot weather of mid-August, and although they worked for about a month together, the bulk of the creative work, especially for Adams, took place after their field work was finished. One feature of the fieldwork was that they used each other’s cameras — each had mechanical problems with their equipment — but they also just swapped cameras at times, so attribution of photographs is uncertain. Adding to the difficulty is that Adams had his lab technician developing the photographs from all the negatives. So a typical attribution in this book reads “Dorothea Lange [and Ansel Adams]”, emphasizing the cooperation but also the difficulties. One of my favorite examples of this appears on p. 115, from the photography in Gunlock. Swensen’s text reads: “As the sun progressed toward the western sky Adams set up his camera on the top of his Cadillac wagon and focused his lens down Gunlock’s dirt road. Soon the youth of town started to show up. The first was Darlene Hunt, who was soon standing on her horse” (114 — this information comes from an interview with Mary Ellen Hunt Strong in 2011). I can’t help but feel that Darlene may have been imitating the photographer standing on his ride, perhaps even ribbing him. But the photo is attributed to “Dorothea Lange [and Ansel Adams]”, so it may have been Lange who shot it — or perhaps she only planned it.

Swensen notes that “During their search for the symbols of the West, Lange and Adams did not photograph Native Americans. They would pursue images of cowboys but not Indians” (71). This would have been out-of-keeping with Lange’s ideas, despite the fact that Toquerville was named for Toquer, a Paiute chief, a bit of history which Lange most likely knew. But she had planned to shoot the Mormon presence, and Indians didn’t fit in with that plan. Swensen also notes that, despite its isolation, there were other signs of the nation’s interest in this rugged land: “polygamist raids [at Short Creek] and nearby nuclear testing” (5) were both in the news and in the air. All of this the crew noted, in one way or another, but did not focus on.

Swensen devotes 11 pages — all of chapter eight — to Lange’s work in laying out the photographs, and Dixon’s text, as if for an exhibition. And she may well have wanted to exhibit the photos that way. There are photographs of the nine exhibition boards in that chapter, which look to be about 4’x10′, to judge from the hands supporting them. By that point, so thorough has been Swensen’s documentation, that I could recognize all of the photos despite the much-reduced size of the images on the page. By my count there are ninety-four images on the boards. The groupings are fascinating, confirming that “Lange was no longer interested in the single image, or the ‘Bull’s Eye Approach,’ but, rather, groupings that could express ‘relationships, equivalents, progressions, contradictions, positives and negatives'” (210 — the quotes are from Dorothea Lange Looks at the American Country Woman, a posthumous exhibition catalog). When they were finished with the developing, writing, and exhibition boards, work of which Adams said “It is really VERY fine … I am pleased. She is extremely sensitive along the lines of putting things together” (217), Lange took the completed boards to New York, in March of 1954, to the offices of Life, and reported to Adams that the project was well received. She thought it might be presented intact.

She was wrong. The editors selected thirty-five of the ninety-four images, largely following the concept expressed in Dixon’s text that Toquerville was in decay, Gunlock was young and energetic, and St. George was worldly and modern. Adams “called it a caricature” of the exhibit, and “fretted that only seven of his works, as opposed to twenty-eight of Lange’s, were selected” (218) — although the problem of attribution makes that a difficult statement to evaluate. But that was the least of their worries. Reaction to the story, as I mentioned above, was negative from J. Reuben Clark and from the residents of Toquerville. The second page of the article, the right-hand page of two devoted to the town, bore the headline, in large type, “Toquerville is old and quiet but its children have gone away” (223, and page 92 in the magazine). That was a contested statement, as Swensen notes; Lange and Adams took as many pictures of the town and its children as they took in Gunlock, but many of them did not make it onto the exhibition boards, and none were in the article. The editors of Life shaped the article as much to Dixon’s text as to the photographs. One of the women in Toquerville, Vera Beatty, consulted a lawyer in St. George, then sought damages — she felt her picture, showing her “in her canning apron, housedress, and disheveled hair” (223) was offensive. “She felt humiliated that she was presented to millions of people in this way without her knowledge or consent” (223-4), and asked for $1,000 in damages from Life. They forwarded the request to Lange, who would have the consent forms. Swensen does not indicate whether she received any money.

Adams visited Gunlock, St. George and Toquerville in an attempt to make amends. He also felt that the team had acted unethically in not emphasizing that these pictures were for a national publication, and wrote a long letter to Lange expressing his feelings. If Beatty’s statement were correct that she had been photographed for a national publication “without her knowledge or consent,” Adams would be correct in his feeling that they had acted unethically. In the end, the article was felt by Adams and Lange to have been a bust. It did, however, jump-start Daniel Dixon’s career as a writer.

I enjoyed reading the book. I enjoyed looking at all the photographs. I wish the pictures of all the paintings that introduce the book had been printed in color. More than anything else, I am strongly impressed by the depth of Swensen’s research and his willingness to interview people he could locate who were living in those towns at the time of the project. This book has bridged a gap of 64 years for me, but it deserves to be read for all that it has to say, and show, about life in that corner of Utah, where all three towns are still alive, along with all those not photographed by Lange and Adams.

.

Your analysis of this text is very valuable, Dennis. Thank you. I’ll have to run down this book.