Review

=======

Title: The Agitated Heart

Title: The Agitated Heart

Author: J. Scott Bronson

Publisher: ArcPoint Media (Orem, UT)

Genre: Novella

Year Published: 2015

Number of Pages: 207

Binding: Paper

ISBN13: 978-0-9743155-1-5

Price: $12.99

Reviewed by Julie J. Nichols for the Association for Mormon Letters

A surprising number of newly published works of LDS fiction are by middle-aged to oldish authors who’ve been lurking, apparently growing in wisdom and wherewithal, for decades–Karen Rosenbaum. Me. And now Scott Bronson.

Scott’s been doing theater in many places for many years. You can Google him and find his filmography as well as his bio, so much so that when Margaret Blair Young was charged with putting together a panel of Mormon artists last month to celebrate Dialogue’s Diamond Jubilee, she recruited Scott and Tom Rogers and Sterling Van Wagenen, all big theater names, and then me, not such a big name, but local and newly published and therefore perhaps a good token female novelist to set off all those dramaturgs. Tom stepped up on his own and gathered in Eric Samuelson (beloved retired dramatist from BYU) and Brian Kershisnik (beloved artist), thinking, I guess, and probably rightly, that the panel would be better rounded out if they were included. He gave us all copies of his recently published collection of essays, and Scott had come prepared with his new book too. He’s not just an actor/professor/director/ playwright/award winner, not just the artistic director of Provo’s Covey Center for the Arts. (Listen to me: “Not just”!) He’s been working on this book as long as I’d been working on mine, a story he tells with humor and grace at the end of the novella. So I begged a copy, not having had the pleasure of hearing of it before that day. Here is how I was rewarded.

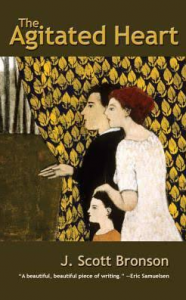

The beautiful cover is Kershisnik’s haunting “Curtain,” wherein a man and his wife and their child (the mother’s hand on the child’s head) draw back a leafy veil behind which can be seen a real forest. They urge forward, eager to see the reality behind the curtain. It’s the perfect metaphor for the novella’s themes: family members striving to be united, seeking to pierce the veil of illusion, struggling to find peace in the face of the unknown.

The epigraph is Robert Frost’s “Revelation,” from which the title comes: “But oh, the agitated heart/Till someone really find us out.//…// So all who hide too well away/ Must speak and tell us where they are”–again, the perfect foreword to the unspoken self-constraints that hamper each character, but that also motivate them, cause them deep pain, and provide unasked-for incentives for the actions that make the plot spin.

The prologue: “Christopher Jacob Arnold sought peace for many days.” The search for peace is a principal theme here. The Arnolds are a family in crisis, and in this way the novella reminds me of Jenn Ashworth’s The Friday Gospels and Carys Bray’s A Song for Issy Bradley, two British novels from 2013 and 2014 in which LDS families are in similar crises. Unlike the characters in the British works, though, Bronson’s family are faithful, dyed-in-the-wool Utah members, not at all wrestling with first-generation angst and misunderstanding (as are the Leekys and the Bradleys). Father Marcus is a popular elders quorum instructor; his wife, Susan, is the Primary president. Stutterer Kari is almost eight, nervous about baptism, and eleven-year-old Christopher is the (anti-)hero who opens the novella as he responds to an unusual Sunday School class, where the teacher draws on the board a graphic representation of Christ’s suffering in the Garden, a representation that moves all the Valiant 11s to tears.

It’s a gripping opening scene. What would move a Sunday School teacher to chalk great gobs and flows of blood from the pores of a praying Christ? But he does; and the whole family rises to it as they hear about it, each from their own secret guilt and anguish. The rest of the novella–which takes place over the next five days–recounts through each of them, individually and finally together, the implications of the Atonement in their family’s life.

Christopher is being seriously bullied at school. Marcus and Susan are experiencing some (not trivial) difficulties in their marriage due to idiosyncratic hangups about perfection and about their roles in their partnership. And Kari, like most seven-year-olds, is trying hard to learn who and what is “right,” what she *ought* to do and what she *can* do. Christopher is the only person she feels she can tell that she really doesn’t want to be baptized. But he’s got his own problems.

Alternating the point of view among the four members of the family, Bronson does a beautifully subtle job of showing how we excuse ourselves privately and publicly, make things worse by attempting to rectify our errors, strive to fix one thing only to exacerbate another. Painful and poignant, the plot grows quickly more constrictive. As the bullying intensifies, so do the mistakes Susan and Marcus make in their misdirected concern for Christopher and their inadequacy in comprehending Kari’s fears. Confrontations; blessings gone wrong; dreams; images exquisite but horribly private, not externalized, of confession, disclosure, repentance and redemption–these snowball as the week draws to its awful close. The meaning of the Atonement unfolds (without ever being named outright) as children and parents do their best to salvage goodness, rightness, from the fallout of undeservedly terrible circumstances.

Fiction has multiple functions in the lives and minds of both readers and writers. The story of the genesis of “this troubling little tale” (206) implies that composing it–a twenty-year process–was a matter for Bronson not only of interrogating the minutiae of marriage and parenthood, but also exploring the essence of Christ’s mission of sacrifice, forgiveness, and love. For readers, now, this beautifully-produced little volume serves as a tightly-constructed, eloquent set of signs and symbols regarding our fallibility and the need for Christ. It’s a small classic. All who are mature enough to love and fear for their families should read it. I hope there will be more where this came from. We can never get too much wisdom.