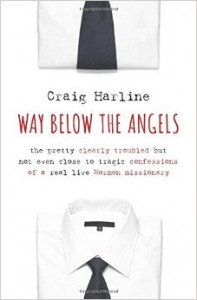

Today’s guest post is by Craig Harline. Harline’s 2014 missionary memoir Way Below The Angels: The pretty clearly troubled but not even close to tragic confessions of a real live Mormon missionary was named the 2014 Best Personal History/Memoir by the Mormon scholarly blog Juvenile Instructor, was a finalist for the AML Creative Non-Fiction Award, is a finalist for Foreword Reviews‘ INDIEFAB Book of the Year Award for Religion, and received a starred review from Publishers Weekly. His book bio reads, “Craig Harline is the author of Sunday: A History of the First Day from Babylonia to the Super Bowl and Conversions: Two Family Stories from the Reformation and Modern America, which was named one of 2011’s Top Ten Books in Religion by Publishers Weekly. He teaches European history at Brigham Young University. Learn more about him at www.craigharline.com.” Craig today is writing about working with Eerdmans Publishing, a 100-year old independent publisher from Grand Rapids which specializes in academic and theological Christian books.

Today’s guest post is by Craig Harline. Harline’s 2014 missionary memoir Way Below The Angels: The pretty clearly troubled but not even close to tragic confessions of a real live Mormon missionary was named the 2014 Best Personal History/Memoir by the Mormon scholarly blog Juvenile Instructor, was a finalist for the AML Creative Non-Fiction Award, is a finalist for Foreword Reviews‘ INDIEFAB Book of the Year Award for Religion, and received a starred review from Publishers Weekly. His book bio reads, “Craig Harline is the author of Sunday: A History of the First Day from Babylonia to the Super Bowl and Conversions: Two Family Stories from the Reformation and Modern America, which was named one of 2011’s Top Ten Books in Religion by Publishers Weekly. He teaches European history at Brigham Young University. Learn more about him at www.craigharline.com.” Craig today is writing about working with Eerdmans Publishing, a 100-year old independent publisher from Grand Rapids which specializes in academic and theological Christian books.

A Mormon in the (Eerdmans) House

Why would a former Mormon-missionary want to publish his presumably very Mormon account of his presumably very Mormon mission with a venerable old (sic) Christian publisher like Eerdmans?

Or even more to the point, why would venerable old (yes) Eerdmans want to publish such a Mormony thing as that? Especially since as recently as 1989 Eerdmans published a thing called The Four Major Cults, and guess who was one of them?

I can speak with (some) certainty only about myself, of course, but I’m pretty sure that the answer to both questions is basically the same, and it’s this: Way Below the Angels is meant just as much for other-believers as it is for Mormons.

If it were more the triumphalist-faith-promoting sort of thing, meant to inspire Mormons and alienate just about everyone else, then I would indeed have sent it to a Mormon-oriented press, where triumphalist-faith-promoting sorts of things about missions have pretty much, well, triumphed.

And if it were more the real-inside-story-about-an-obviously-ridiculous-faith-tradition-by-someone-who-saw-the-light-and-thank-goodness-got-out-just-in-time sort of thing, meant to confirm the suspicions of outsiders and alienate just about all Mormons, then maybe I could have interested one of the really big publishing houses, where real-inside-story sorts of things are pretty much de rigueur.

But my story (and most mission-stories) didn’t feel like it fit either one of those long-prevailing sorts of things (as the big publishing houses confirmed to me). Instead it felt like something that any type of believer (including Mormons) might relate to. And where better to try to reach a crowd like that than venerable old Christian-publishing Eerdmans?

Ironically, it was being a missionary, and then later a historian of the Reformation, that got me a lot more interested in “relating” to other-believers than in converting them. And for me the best way to relate has always been through sharing warts-and-all faith-experiences, rather than talking (arguing) about theology.

There’s nothing wrong (morally) with talking (arguing) about theology, of course. In fact it’s usually what people interested in improving relations between people of different faith-traditions think of doing first, in the hope of finding things you can agree on. But it doesn’t always improve relations, or understanding—and not necessarily so much because the respective parties inevitably won’t agree on everything, but because they still don’t relate to each other as people, or in other words still haven’t really seen themselves in each other.

My friend David Dominguez, who as an evangelical law professor at BYU knows a little something about interfaith relating, says that even more important than talking with other-believers about theology is walking with them. Sure, walking usually includes talking, but the sort of walking and talking he has in mind is like the sort on the road to Emmaus, which “teaches us to approach each other gently, with the utmost of care for each other’s well-being…, matching each other stride for stride, doing all we can to catch up with the hope and despair we all experience in the practice of Christian faith. Only after we have traveled miles together and given each other time to tell the whole story can we open up the Word in the here and now, among real brothers and sisters, rather than engage in debates over abstract doctrine.”

I think I’d be totally onboard with a rule that says, “No talking (arguing) about theology (or anything else for that matter) until you’ve shared enough of your warts-and-all story with your co-talkers that you can see yourself in them—and not just to keep the noise-level down or as some polite preliminary to the main show, but because seeing yourself in another person actually changes the talking (arguing).”

Oh, seeing someone like that wouldn’t solve everything, and maybe wouldn’t bring world peace (actually maybe it would), and you’d still disagree on assorted things.

But you’d disagree now with empathy and informed understanding, instead of mistrust and suspicion.

And you’d try your darndest to characterize the views of the other person fairly, instead of carelessly or distortedly.

And you’d stop reducing that person to simply a member of a group.

And you’d be happy instead of alarmed about what you had in common.

And you’d be open to learning things from another person’s tradition that aren’t in your own.

And when you saw things in the other person’s tradition that seemed obviously silly and merely culturally bound, you’d be more willing to reflect on things in your own tradition that were very possibly of the selfsame ilk.

But again most of all you’d be inclined to see that other person as someone basically like you, instead of as someone basically not.

Of course some people don’t want to see themselves in the other, like congregants in the Reformation who complained when their preachers didn’t rail enough against enemies of the faith: they needed those enemies in order to define themselves! And in fact once you start seeing yourself in someone, it’s hard to go back, because it’s interesting, and comforting, and satisfying.

Eerdmans itself has plenty of warts-and-all memoirs that offer even former Mormon-missionaries the chance to see themselves in unexpected others—like Lamin Sanneh’s Summoned From the Margin, or Rembert Weakland’s A Pilgrim in a Pilgrim Church, or Dorothy Dickens Meyerink’s Ministry Among the Maya. Books like these even made me think that maybe others would see themselves in my story too—see the humanness in Mormon missionaries, instead of the usual demonicness, roboticness, or (thanks to the musical) moronicness. I’m glad Eerdmans seemed to see that too.

But of course I hope just as much that many of my fellow Mormons will be able to see that humanness in the book as well, instead of the usual (at least for those who haven’t been on missions) angelicness. And thus see something of themselves most of all.

(For another story about a Mormon author publishing with a mainline Christian publisher, see this essay by Darrel Nelson.)

Well said. I teach at BYU-Hawaii and I am often and mostly encouraged by the rising generation’s openness to interfaith dialogue and ability to see past the triumphalist model. Maybe the internet really is able to shrink the world and tamp down ignorance (probably as often as encourages it). I teach catholic essayist Brian Doyle in some of my classes and his book is almost always the popular thing on the syllabus because students are so inspired and surprised by how similar his testimony of God and goodness is to their own. (Also, his essays are very short.) Slowly but surely. I hope to grab a copy of your book soon.

Also, I had your nephew in my home the other evening. Eric, I think? He seems like a good kid. He was accompanying a friend of his who babysits for us. We got to talking and he mentioned you. So . . . there’s that.

Thanks Joe, I was interested to hear about your students’ reactions. And yes Eric is my good-kid nephew indeed.