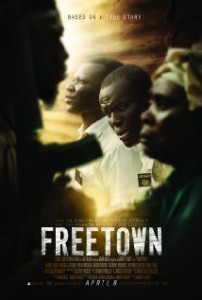

Reviews for Freetown, which opened April 8.

Reviews for Freetown, which opened April 8.

Sean Means, Salt Lake Tribune. 3 stars. “The Mormon-themed adventure drama “Freetown” cements Utah director Garrett Batty’s trademark — after his 2013 thriller “The Saratov Approach” — to meld an intense narrative with a thoughtful look at faith . . . Batty and his team filmed in Ghana, two countries over from Liberia, with local cast and crew — which brings stunning landscapes and a remarkable level of authenticity to the film . . . Through the adventure, both powerful and funny, Batty and co-screenwriter Melissa Leilani Larson (a Utah playwright whose “Pilot Program” is premiering at Plan-B Theatre Company) also create a deeply moving depiction of day-to-day missionary work. The missionaries, even when in danger, are determined to teach and share their belief in the LDS Church — and that missionary zeal carries them through the roughest patches of their journey. “Freetown” is that rare Mormon-themed drama that isn’t pitched solely at LDS audiences. It’s a solidly structured drama that has something to offer people of all faiths.”

Roger Moore. Tribune Review Service. 1.5 stars. “Garrett Batty’s “inspired by a true story” film is most at home capturing a country descending into chaos — the myopia of seeing a war up close. Locals and missionaries flee to the sanctuary of a church, randomly hunted by disorganized thugs piling out of pickup trucks, enforcing their reign of terror at the barrel of an AK-47 . . . The acting varies from passable to rote, wooden recitation. And there’s a hint of humor . . . But the film takes over an hour to get underway, and dawdles even after it’s hit the road. The impending peril is feebly handled, the Biblical allegories (one Elder denies his tribe) a trifle heavy-handed. Inter-African “racism” (tribalism, actually) is discussed, but not the then-current racist reputation of the church these young African men had joined. Perhaps they weren’t told. So as odysseys go, “Freetown” is a short trip, and the incidents during it hardly seem the stuff of great drama, with or without “miracles.””

[Moore says that racism in the Church was not discussed, but I understand that the priesthood restriction is discussed in the film. Moore’s reviews are syndicated to many newspapers.]

Josh Terry, Deseret News. 3.5 stars. “Faith is exhausting. That is the message of “Freetown,” . . . All of this leads to some very tense moments as the missionaries confront agitated rebels and other obstacles along the road. Time after time, they encounter roadblocks, both literal and figurative, only to find miraculous means to move on to the next stage of the journey. The experience is intentionally exhausting, and Batty uses some well-timed humor to lighten the tone. Though the missionaries are the focus, Abubakar is the true protagonist, and the test of his faith becomes the centerpiece of “Freetown’s” narrative journey. One of “Freetown’s” biggest triumphs is the way it maximizes a comparatively small budget. Rather than relying on a lot of close-up shots that betray a lack of funding and production, Batty uses drone cameras and overhead shots to give the audience a Hollywood-level perspective of “Freetown’s” setting. It’s also interesting to note how “Freetown” continues a theme Batty mined in “Saratov.” On the surface, both films explore “missionaries in danger” scenarios taken directly from the history books. But at a deeper level, both films are asking questions about the endurance of faith while confronting violent circumstances with non-violent resistance. The protagonists of both films are given the opportunity to use violence as a means for their deliverance, and based on what contemporary audiences are accustomed to — even in “true” stories — it’s surprising that they don’t follow through. That isn’t to say “Freetown” is a violence-free film. While Batty never opts for any graphic content, he also doesn’t shy away from the harsh reality of the conflict. Victims may be killed off-camera, but their innocence is felt center stage. In total, “Freetown” delivers a powerful message despite limited means, and marks another success for an emerging filmmaker.”

Adam Mast. Southern Utah Independent. 3.5 stars. “The cast, led by Adofo and Phillip Adukunle Michael, is appealing. While “Freetown” features a plot that isn’t exactly all sunshine and rainbows, it does find moments of humor, and it’s a testament to the cast’s naturalistic abilities that “Freetown” offers warmth even though the subject matter tends to be somewhat dark. Batty and crew deserve extra props for finding the resources and drive to shoot this movie in less then three weeks on what I’m told was a very limited budget. A few shaky drone shots aside, they managed to pull it off. If I have any issue at all with “Freetown,” it’s that the film as a whole doesn’t feel quite as intense and perilous as the actual story that inspired it. Listening to the real life Marcus Menti (portrayed in the movie by Michael Attram) speak to the audience following the screening I attended proved to be a very moving experience, and it prompted me to look a little deeper into the actual story on which this film was based. I discovered that what these missionaries endured was considerably more intense than the film would have you believe. But then, making a movie based on a true story is always a tight rope act, and in the case of “Freetown,” Batty and crew opted to tone things down a bit in an effort to reach a larger audience. Clearly the story behind these missionaries and their ordeal is an inspirational one, but again, I wish the sense of danger would have been as front and center as it was in “The Saratov Approach.” Having said that,”Freetown” is certainly worth seeing. Not only is it an insightful culture lesson, but it also offers up a heartfelt message of faith, regardless of your personal beliefs.”

Frank Scheck. Hollywood Reporter. “Despite the storyline’s inherent drama, the meandering Freetown, much like the characters it depicts, takes far too long to get to its destination . . . The screenplay by Batty and Melissa Leilani Larson handles its religious themes in relatively subtle fashion, concentrating on the suspenseful story mechanics rather than delivering bluntly imparted messages. Still, there is much talk of miracles, as the young men defy seemingly insurmountable odds including numerous roadblocks, rebels who demand payment for allowing them to pass through, and the maniacal determination of their leader (Bill Myers) who menacingly asks everyone with whom he comes into contact, “Are you a Krahn?” Although suffused with welcome touches of sly humor, the proceedings never gather the necessary dramatic momentum. With most of the violence discreetly rendered off-camera, the danger is insufficiently conveyed, although the Ghana-shot film successfully evokes the war-torn African milieu. Unconvincingly acted with the exception of Adofo, who brings a convincing intensity to his performance as the young men’s would-be savior, Freetown–much like the director’s similarly themed previous effort, 2013’s The Saratov Approach, about missionaries kidnapped in Russia–is unlikely to find much of an audience beyond its supportive Mormon base.”

Stephen Carter, Sunstone Magazine. (A review of both Freetown and The Cokeville Miracle.) “If The Cokeville Miracle patrols the borders of what it means to be a believer, Freetown explodes them. In some ways, Freetown is a conventional faith-promoting, based-on-true-events story: a group of missionaries miraculously escapes war-torn Liberia into Sierra Leon. But the movie also breaks just about every rule in the faith-promoting-genre handbook. First, this is a heavy, frightening film. It takes place in a political environment that seems to have no good guys . . . Can a man involved with genocide be a believer? Freetown seems to take the radical approach of defining a believer as any deeply imperfect soul: perhaps blind and destructive, but still on an unpredictable, eternal, and entirely personal journey of his or her own . . . So, though there are some physical miracles along the way, the story focuses on the miracles taking place inside people’s hearts. One particularly moving scene involves Phillip talking with a missionary about when they found out about the priesthood ban. Being African men, the discovery was especially painful. But the missionary doesn’t try to explain the issue away; he simply points out that we’re all changing, that we’re all trying to make ourselves better, and that our constant search for betterment is the crux of the gospel. Later, the Krahn missionary says something to the effect of, “Many horrible things have happened that will affect us permanently. We can’t do anything about them. All we can do is try to make something good happen now.” Freetown’s willingness to allow opposition to be potent and permanent gives these moments of grace an enduring power.”

Kevin Burtt, LDS Cinema Online. B+. “Like The Saratov Approach, Batty has taken another true story where the ending is already known and found ways to craft a tense and focused experience. Freetown is an effective tale of survival and spirituality that shows Batty as one of the top LDS directors today . . . I liked how the missionaries in Freetown are shown to be committed and joyous in the gospel, as well as energetic about sharing it with their neighbors3. I also liked how Freetown portrays the missionaries when chaos breaks out. They observe the situation and make the best decisions they can, without sitting around and waiting for the mission president or Area Authority to tell them what to do. They do what it takes to survive and assist others, regardless of “mission rules” . . . There may be two potential criticisms to Freetown: one, the missionaries are clumped together interchangeably for most of the movie and don’t get many individual characterizations or personal elements. Other than Elder Gaye (the Krahn elder) we don’t know much about the others (or could probably even list their names without looking them up.) Regrettable, but not something the screenwriters could have dealt with easily with all six elders stuck in a cramped car for much of the film. On the other hand, we do get to know the mission leader Brother Abubakar, who is selfless and dependable even as he has his own under-the-radar faith crisis that the journey with the missionaries helps alleviate. Secondly, the film’s narrow scope is somewhat limiting. By focusing exclusively on the missionaries and their journey, the other natives (who don’t have the luxury of fleeing like the elders) who have to find a way to survive in Liberia amidst the violence are essentially forgotten. However, Freetown has been designed to be “the missionaries’ story” and I think that’s acceptable as part of the premise. (A more expanded scope that covered more groups of people and their experiences may have made for a more robust film, but that’s a minor complaint). There are a few key themes in Freetown: there’s a natural undercurrent of “why do bad things happen to good people” when violence breaks out and innocents start dying,5 which the elders ponder but don’t dwell on. Personal identity and pride is another — Elder Gaye ponders whether he should stick up for who he is when interrogated by the rebels, or simply lie about his tribe to keep from being shot. Being ‘honest’ in such a simple matter isn’t worth dying for, right? Especially when he can accomplish more for his people by surviving. (“It’s not cowardice to survive. Don’t betray your tribe, preserve it!”) However, when others of his tribe proclaim their identity proudly in the face of a gun barrel and pay the price, he starts to wonder whether it’s fair not to share the same destiny . . . Many other LDS filmmakers would have avoided this subject entirely, either to avoid “controversy” or with the argument that it is irrelevant to the story. But in fact it’s not, as I believe the filmmakers realized themselves — the experience of the native missionaries’ gospel idealism being tempered immediately by finding out about ‘mistakes’ in Church history and the messiness of overcoming ‘tribal’ boundaries even within gospel followers is directly appropriate to the tribalism theme. (And the elder who brings it up has a nice line afterwards: “God wants us to change, to improve, to move forward. When any man changes, God rejoices.”) . . . Freetown represents great filmmaking that is both tense, entertaining, and spiritually enlightening. With this and The Saratov Approach, Garrett Batty has thrust himself into the forefront of LDS filmmakers today.”

Ngyuen Le, The Script Lab. “As a film with a religious message, Freetown scores. As a film, this genuine effort has a few rough edges . . . By now with “based on true events” films, audiences might go “yeah, right” from the outset. For Freetown, however, they will likely reserve or eliminate the notion thanks to the film’s effort in making every aspect so grounded, so honest. Accra, Ghana stands in for Liberia, but every scene is shot on location. The performers on screen? All are local. Surrounding these welcoming details are director of photography Jeremy Prusso’s thoughtful framing choices, Robert Allen Elliott’s stirring score that mixes African chants with a bit of Harry Gregson-Williams, effective use of sounds, the occasional smart dialogue and powerful sequences from Melissa Leilani Larson and Batty’s script. Unfortunately (and interestingly), each of the aforementioned pros manages to show its other side as well. The music appears in scenes where silence is the better choice. Certain moments, sweat-inducing or enlightening, have their effect ruined instead of realized, heavy-handed as opposed to natural. The actors playing the Elders are better when together; in their isolated sequences their performances range from acceptable to questionable. Extras, on more than one occasion, smile when they are not supposed to. Also worth noting are a bizarrely staged nighttime supply-gathering sequence, Batty’s tendency to include an overhead shot – some welcoming, some arbitrary – and the screenplay’s close brushes into preaching territory. The latter is made worse when the wording, from two Utah writers, is perhaps too complex for our performers; it is difficult to make out what they say at times (if not due to this then it is the overpowering music). The largest issue, nevertheless, is this: Batty’s straightforward approach. On one hand, this is ideal as it steers the film from Hollywoodization and makes moments of drama (ones without distractions) and humor click better. On the other hand, the sincerity breeds more than a couple of snails in the film’s pacing when, from reading the plot alone, they have every right to expect a fast-paced, tension-all-around journey before the theater lights go dim. Despite being a refreshing entry in the religious film genre because it avoids exaggeration or constant belief-affirming/questioning moments, Freetown has flaws in its craft that have viewers enjoy at one point and perplexed the next. Ultimately, the film provides a torn experience upon watching as its “no surprises” nature means “where is the entertainment factor,” but all the investment – creative and otherwise – is so true you are bound to find the film endearing.”

Mahonri Stewart. “As much as I loved Saratov Approach, it was seeing Freetown last night that truly rekindled my hope in Mormon Cinema. Far from being the wheezing gasps of a dying genre, Freetown is now representative of the height of LDS Film. We’ll see if it is able to capture a robust Mormon audience once it is released on April 8, but in terms of quality, it is by far the best Mormon film I have seen . . . Larson’s writing is one of the many strengths of the film. There is nuance, subtlety, yet power in her writing. The film never seems overwrought. Larson never gives into the temptation to be overdramatic, despite the fact that the subject matter could have easily veered her in that direction. Instead we get these beautifully intimate moments, even in the most severe of situations, that focus on her characters’ inner lives, their doubts, their faith, their flaws, their vivid triumphs. The dialogue is often deceptively simple, revealing so much with so little, that you feel your breath quiet a bit to get the full effect. In choosing Larson, Batty solidified a voice in the film that is soulful and wise; tragic, yet hopeful; and achingly lovely . . . It is perhaps the film in Mormon Cinema’s canon that most transcends its local, Utah origins, and thus makes Mormonism appear as a powerful, international force of faith, rather than a provincial, American religion. The fact that the only white characters we see are the mission president and his wife (who probably have no more than five or ten minutes of screen time) is telling. This shows that Mormonism is no longer just a white American’s story. Mormonism is a global force now, and perhaps it is the white Mormons in Utah who most need to hear that message. We need to start thinking bigger, and not focus on the little community disputes around us, and thinking that somehow reflects the global Church. Jokes about Jell-O, or political rants that only effect Americans, should no longer be represented as the Mormon story. The Mormon story now has global impact and should have a global representation . . . Freetown shines on the hill as a bright hope, not only for Mormon cinema, but for us a global family of faith. That pure message of faith and progress that the film conveys has come at a timely moment. Batty, Larson, Abel, and all those involved in the film should be warmly thanked and congratulated.”

Aleah Ingram, LDS Daily. “Freetown is a raw, beautifully-crafted labor of love from Batty, Abel, and their team. Not only is the message profound, but the film entertains and offers more for your dollar than most offerings found in theaters today.”

Rich Bonaduce, Ogden Standard-Examiner. 2.5 stars. “The term LDS cinema has a bit of baggage associated with it. Most films of this home-grown variety have too many in-jokes and not enough production value; content to lean on lazy Mormon stereotypes and shoot in Utah. Not so with “Freetown,” . . . Beautifully shot on location in Ghana with professional actors who also happen to be LDS, “Freetown” has a weight to it that you just can’t get when “hiring” your buddies who once did stand up to star in your film shot at your uncle’s farm in Box Elder County. This is good since the real events on which this story is based are pretty dire . . . It comes off in the movie as mostly luck, although you won’t hear that from the woefully naive missionaries who have a frustratingly low bar for what constitutes a miracle. And herein lies what I consider to be the problem with most LDS Cinema offerings: not only do they preach simply to the choir, they preach down to them, simplemindedly . . . instead of some well-thought out planning, he is treated to the child-like innocence of the flock, wide-eyed and oblivious to such realities. Not enough petrol? Have faith. Checkpoints at every corner? Have faith. Guys with guns? Have faith . . . Further, Abubakar is the audience stand-in asking all of the tough questions, but maddeningly he also buys into the silliest of answers. When a particularly nosy checkpoint guard ends up waving you on because you start trying to convert him that’s not a miracle – that’s what every missionary who’s ever had a door shut in their face experiences. And when you’re almost at your destination and your only roadway is under construction, taking a boat on the nearby river is not a miracle, it’s basic transportation. One missionary has a heartfelt moment with Abubakar during the long road trip to Freetown. He expresses his misgivings when he was being converted upon discovering that the LDS church used to disallow blacks from the priesthood and temple ceremonies until very recently (the late ’70s). I applaud the film for even bringing up this issue. It’s a great question and one that would obviously come up on an LDS mission in Liberia. He asks how such a righteous church could be so wrong? He asks how could a church with a prophet at its head who speaks to God be so racist? But his struggle is dodged with some vague mumblings about Christ’s atonement, again in a way that will pacify the flock but frustrate everyone else . . . “Freetown” is certainly well-produced, but waffles on its theme, avoids the big questions, and presents its heroes as simpleminded.”

Mark Savlov, Austin Chronicle. 3 stars. “Faith-based filmmaking has had a hell of a time when it comes to putting nonbelievers in seats. Try though they might, Christian filmmakers have yet to sway the critical and popular perception that God – any god, pick your favorite! – belongs in a house of worship and not on the cineplex screen, that favorite of idolators everywhere. Heaven Is for Real, God’s Not Dead, and The Book of Mormon Movie, Volume 1: The Journey end up being too preachy or too poorly made, or just plain wander off into the narrative wilderness for what feels like 40 years. This isn’t the case, thank God, with Freetown, the second feature from Mormon director Batty . . . The Mormon faith is never played down for the sake of lay audiences in this unusually gripping story. There’s even comedy, of a sort, when one elder literally bores his way through yet another trigger-tense roadblock by proselytizing: “If you receive his gospel and repent, you will be happy. I’d love to share more with your friends!” he hollers as the elders are hastily waved through to the chagrin of the rebel gatekeeper. Divine providence, indeed. Given the Mormon church’s notorious history when it comes to people of color, interracial marriage, and, while we’re at it, their recently updated views on LGBT and gender equality issues, skeptics might wonder if this is all a very pricey PR gimmick. Probably not. Cinematographer Jeremy Prusso catches some stunning imagery, Robert Allen Elliott’s score is genuinely stirring, and the cast, most of whom are from Monrovia, is uniformly excellent.”

Dwight Brown, Black Press USA, Huffington Post. “It’s an urgent escape. Like the Jewish people leaving Germany in the face of imminent death. Only, this journey to freedom takes place in Liberia and involves the personal story of six Christian missionaries. The film, based on true events, feels dramatic and thrilling at moments. Other times, its heavy-handed proselytizing mars the proceedings. While the preachy nature may put off general audiences, it may inspire the faith-based crowd. Who knows? . . . The First Liberian Civil War, an internal conflict in Liberia that raged from 1989 until 1997, killed over 200,000 people and eventually led to the involvement of the United Nations. This tiny slim-focused film fails to reflect the magnitude of that aggression. It sets up the characters, in a very insular way. As you watch the missionaries face danger in their neighborhoods, you have no idea that the entire country is aflame. It would have been helpful if the footage included TV news reports, or radio reports that let the viewer know that there really wasn’t any place to hide. That lack of perspective is just one of the script’s big faults. The other looming misfire is the tendency for the dialogue to get weighed down in bible talk and spiritual dogma. The characters are set, their dilemma is noted, their antagonists brutal—that’s enough for audiences. If faith and serendipity are going to get the group through their crisis, show it, don’t’ talk about it. The average filmgoer will get the message that the group is blessed and a higher power is looking out for them. Hammering it, over and over again, makes the movie pedantic, like a long-winded sermon. The film goes on for 116 minutes, when it could have been edited down to 100 minutes tops. The cinematography, by Jeremy Prusso, makes the lush landscape of West Africa so inviting. The perfect lighting of the dark complexions makes the skin look radiant. The musical score by Robert Allen Elliott dramatizes the footage in ways it needs at points, though sometimes it is almost overbearing . . . Freetown doesn’t tell its story with the eloquence and understatement of Abderrahmane Sissako’s Timbuktu or the solid dramatic flourishes of Terry George’s Hotel Rwanda. Still, the film depicts a part of African history that is worth knowing and sharing.”

Eric D. Snider. Movie BS with Bayer and Snider. B-. “A solid drama with spiritual elements as well as elements of a Hollywood thriller. It would play better for people of some religious faith, not Mormons specifically. It’s good, a solid B-. If you are the sort of person who would like to see a spiritual drama with some elements of suspense and thrills, then this would be good for you. If you are generally not interested in a spiritual drama, then it is not for you.”

Scott Renshaw, Salt Lake City Weekly. 3 stars (out of four). “There are better and worse ways to approach the concept of “faith-based cinema;” this is one of the better ways. Director Garrett Batty and Utah playwright Melissa Leilani Larson adapt the fact-based story of a group of African LDS missionaries in Monrovia, Liberia circa 1989. As that country is thrown into tribal civil war, local church member Philip Abubakar (Henry Adofo) packs the six missionaries into his Toyota Corolla for a treacherous attempt to reach safety across the border in Freetown, Sierra Leone. As in many such tales, deus ex machine miracles are part of the package, along with plenty of time musing over keeping the faith in the face of difficulties. But Batty’s also working with a genuinely tense life-or-death narrative, and shows the smarts to know when to subvert expectations. It’s a satisfying surprise indeed to find a “Mormon movie” willing to confront the church’s legacy of racism head-on, and even make a joke out of the missionaries being able to escape threatening soldiers who would rather let them go than listen to someone attempting to proselytize them.”

Nick Schager, Film Journal International. “Director Garrett Batty sermonizes with forthright fervor in Freetown, a fact-based story about courage, camaraderie and perseverance that functions as a thinly veiled advertisement for the Church of Latter Day Saints . . . Batty lays out his premise with a modicum of fuss, but from early shots that linger on the missionaries putting on their church-affiliation name tags, to soaring African soundtrack singing over shots of Liberia’s gorgeous landscapes, Freetown steeps itself in a distinctly faith-based atmosphere. That alone isn’t a detriment, though as it charts Abubakar and company’s trials, the film repeatedly strikes the same monotonously preachy chord. Ostensibly the group’s leader, Abubakar is a man undergoing something of a minor spiritual crisis, and as he evades an evil rebel monster intent on stopping the missionaries from attaining freedom across the border, he struggles to believe that God is watching out for him, with Batty and Melissa Leilani Larson’s blunt script making plain at every turn that its prime concern is relating the renewal of his faith. Despite its war-torn setting, Freetown eschews graphic depictions of brutality, confronting the horrors perpetrated by the rebels while nonetheless turning its camera away from them at the last second. Such a pulling-its-punches tactic is in keeping with the general flaccidness of the proceedings . . . Those incidents are staged with reasonable aesthetic competence but very little in the way of suspense or excitement, so that Freetown ultimately feels like a long, uneventful mission toward preordained liberation and salvation. That the film doesn’t even momentarily question its religious characters’ course of action–which involves them abandoning their posts, and their flock–somewhat undercuts such an uplifting trajectory. Yet more frustrating is simply the fact that its dialogue, when not serving a purely dull functional purpose, is designed as an unimaginative mouthpiece for the beliefs of the Church of Latter Day Saints. Draggy and one-note, it’s an indie more interested in reaffirming Mormon dogma than in delivering compelling drama.”

Scott Hales, Mormon Misfits. [Starts with a discussion of the taxonomy of mission movies, and praising the presentation of viewpoints beyond the standard American one.] “Of course, in its attention to faith, Freetown has heavy-handed moments when characters speak profundities as solemn music plays in the background—something The Saratov Approach did as well. Some viewers may find these moments overly preachy and off-putting for the way they offer gospel messages or insights. Personally, I found the words themselves wholly consistent with the way missionaries–and Mormons in general–talk about the gospel with each other. However, I do find the music and the way the actors suddenly look off into the distance unnecessary. I wish the filmmakers had let the words speak for themselves more. They did not need music and distant gazes to make them powerful. This problem aside, Freetown benefits from a strong cast and exceptional production value. The film is beautifully shot on location, providing the film with an impressively authentic look . . . For the past decade, Mormon film has been wallowing in direct-to-DVD flops that have done little more than showcase amateurism. While there have been some standouts—Napoleon Dynamite, Saints and Soldiers—none have done a better job than The Saratov Approach and Freetown in telling stories that remind viewers why Mormonism is so meaningful to those who embrace it. Freetown, first and foremost, is a compelling story, but we should take pride in the fact that it is also a Mormon story . . . The characters are realistically drawn and the situations they find themselves in—including the miracles they encounter along the way—seem wholly plausible. It is a groundbreaking film, and we can only hope that it will lead Mormon film to even greater horizons.”

LaShawn, Rational Faiths. “I was thankful that the movie had nothing to do with cinema stereotypes and so much more to do with what missionaries do best – serve God with their heart, might, minds, and strength . . . There’s a cadence in black speech that links each of us in the Diaspora. It’s simply a way of knowing. It is felt as much as it is spoken. As I watched the story of Black Saints in Liberia, the prayers felt like home. There’s a substance within the prayers of Black people that is different from anything I have words to explain. When Saints pray, they converse with God in a way that is instantaneously connecting and healing. The familiarity with which the missionaries and the members expressed themselves to God in prayer with Him, and in discussions about Him, demonstrated such a personal relationship, solid trust, and commitment to Him and His Word that it was piercing to me. This spiritual current flowed into how they taught about the Gospel when making contacts . . . From funny moments in map planning (simply classic “Elders can make a joke out of anything, even a rock on the hood of a car” types of things) to the decision to find a field where they could readily harvest, these Elders exemplified their understanding of the big picture in this eternal round of their work for the Lord . . . I enjoyed the film’s ability to weave in layers of complexity supported by firm statements of testimony with personal, unequivocal Truths. I wondered if they would mention the Priesthood ban. They did. They discussed conversion and they celebrated God’s joy in us when even one sinner changes from his evil (and implied racist) ways. I appreciated the nuance in their discussion of God’s chosen organization’s connection to the ban versus connecting the ban to God himself. I think my favorite part of the film had to be in seeing the ways the Gospel crossed man-made enemy lines. There are powerful moments of choosing bravery and choosing life, brotherhood, and being knit as one in the film, where I realized that hearts may be turned toward you and toward Christ even when hands are tied by politics and power. I thought about how easy it is for us to watch a movie about “struggling international faithful Latter Day Saints” who battle an easily identified evil that all movie goers can rally against.”

Modern Mormon Men reviews (mini-reviews by Melissa Condie, Pete Codella, Pete Busche, Theric Jepson, Scott Hales, Carrie Stroud, John English, and Dan Oakes). Theric: “I expected to be more thrilled than moved by Freetown. In fact, I was more moved than thrilled. The thriller aspects of the film are competent but not extraordinary. What is extraordinary is the sense of hope and joy the film imparts in balance to the despair and danger. And make no mistake: even though we expect the miracles the missionaries promise and all bloodletting is done offscreen, the reality of the violence and death and finality that was Liberia’s civil war is utterly plain. One of the smart choices of the script is making the protagonist someone other than a missionary. Henry Adofo who plays Philip Abubakar is a powerful lead. He teeters between being a nobody and a hero—or, in other words, he’s fully human and accepting of that. Something about being twenty and wearing a black tag that Broadway doesn’t understand is the attendant joy of being nothing, and how being nothing leads to complete reliance on God and the ability to see all things as possible. Abubakar doesn’t have the luxury of a black tag to render him nothing. Sure, death is no more real to him than it is for the missionaries, but he feels the weight of death differently, being the only adult in the car (which may be why, in the end, it will be his faith that’s necessary if they are to survive). The film presents language intelligently, as we should expect when the words are penned by AML Award-winning playwright Melissa Leilani Larson. The film’s score by Robert Allen Elliott is likewise suitable and intelligent. The problem is that these two strengths can bump into each other. Sometimes, what Freetown really needs, is some more faith in silence. That said, I think the best way to enjoy the film is to take a crowd to the theater. If it makes it to the East Bay, I plan to invite a lot of people. This is a movie that should be experienced communally.”

.

[the film does indeed discuss the priesthood restriction, but nothing is resolved, so . . . maybe Moore felt it did not count?]