The Fluent Imagination

A couple of years ago I decided to learn another language. At first I just dabbled in it and learned a few words and phrases. Then as I learned a little more, I started to become, in stages, hungry, frustrated, intrigued, enchanted, and increasingly confident. Now, two and a half years after beginning, I find myself fluctuating between being hungry to learn more and happily becoming more and more confident. But I know I still have a very long way to go before I actually become fluent. I was thinking about this process of learning a language in relation to the way children develop their imagination. In this case, it is a lot more than just acquiring a good grasp of language. It involves figuring out how to think and make connections between the life within and the life outside of oneself. I believe that just as learning a new language is a long and hard and often rewarding and sometimes frustrating process, so too is learning to cultivate one’s imagination or to stimulate the imagination of a child.

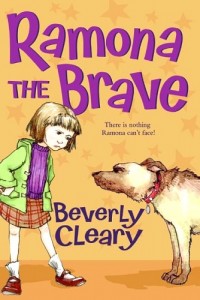

Imagination is much more than just learning to use and apply language, and it is also not limited to fictional, “imaginary” things. The way I see it, developing an imagination depends on being exposed to many opportunities to think creatively. For example, in Beverly Cleary’s book Ramona the Brave, Ramona had to throw one of her shoes at a dog in order to get past him on the way to school. Of course her teacher was concerned when Ramona arrived with only one shoe, so she gave Ramona an old brown boot to wear to protect her foot. But, “Ramona did not want to wear an old brown boot, and she made up her mind she was not going to wear an old brown boot!” Now was the time for Ramona to think creatively and use her imagination. I think I know how she felt because I know the feeling of trying to solve a problem with the resources and raw materials at hand. I can almost feel Ramona’s brain cogs turning as she ponders the situation. “If only she had some heavy paper and a stapler, she could make a slipper, one that might even be strong enough to last until she reached home. She paid attention to number combinations in one part of her mind, while in that private place in the back of her mind she thought about a paper slipper and how she could make one if she only had a stapler.”

Imagination is much more than just learning to use and apply language, and it is also not limited to fictional, “imaginary” things. The way I see it, developing an imagination depends on being exposed to many opportunities to think creatively. For example, in Beverly Cleary’s book Ramona the Brave, Ramona had to throw one of her shoes at a dog in order to get past him on the way to school. Of course her teacher was concerned when Ramona arrived with only one shoe, so she gave Ramona an old brown boot to wear to protect her foot. But, “Ramona did not want to wear an old brown boot, and she made up her mind she was not going to wear an old brown boot!” Now was the time for Ramona to think creatively and use her imagination. I think I know how she felt because I know the feeling of trying to solve a problem with the resources and raw materials at hand. I can almost feel Ramona’s brain cogs turning as she ponders the situation. “If only she had some heavy paper and a stapler, she could make a slipper, one that might even be strong enough to last until she reached home. She paid attention to number combinations in one part of her mind, while in that private place in the back of her mind she thought about a paper slipper and how she could make one if she only had a stapler.”

It’s that private place in the back of a person’s mind that brews up the thoughts that lead to a strong imagination. That quiet spot in one’s own self is one of the most important places in the world, not just for children but for all people because that is where the spring of creativity bubbles up and runs clear. That is the place where children can find the freedom to sit and become acquainted with the workings of their own minds. They need to taste that fresh water and quench their thirst through long summer days and dark nights under the covers with a flashlight. And even grownups need to spend time by the banks of their own spring to protect it from becoming stagnant and ebbing to a sickly trickle. I’m talking here about reading, reading anything and reading everything. It’s not necessary to read only fiction to develop an imagination, but it is important to read something, or to listen to something. Nonfiction can be just as stimulating as a storybook, but the most important thing is to put enough raw material into one’s brain that there is something inside to draw on in times of trouble or boredom or distress.

One discouraging thing I’ve seen is when a young person has very few stories available inside his or her brain. Not long ago I was talking with a young woman who felt very uncomfortable and scared whenever she was alone with just herself for company. Maybe because she hadn’t been exposed to many stories, this young woman replayed over and over in her mind scary television shows she’d seen. She thought she saw kidnappers behind every tree and bad guys lurking in every parked car. Fear had a strong hold on her life because, in part, she hadn’t cultivated the imagination needed to move past the dangers and into thoughts of resolution and safety. She is working on becoming more confident, but I think one of the best ways to prevent this type of paralyzing fear in the first place is to start young and listen to and read lots of stories that show characters in many situations. This will give a young mind many examples of ways to solve problems. Imagination is a necessary ingredient for ingenuity, both in problem solving and in creating new stories.

I contrast the experience of the frightened young woman with the situation of another young girl I know well. Rosemary reads and listens to stories all the time and is constantly reliving some adventure in her mind. When she walks to or from school, she will often pick a handful of pyracatha berries and throw them, one at a time, in front of her. Right before she passes one tossed berry, she throws another one. Once when I was walking with her, I asked her why she was doing this. “For protection,” she said. “If I throw the berry in front of me, and there is one already behind, I will be invisible to the monsters that are following me.” That made a kind of weird sense to me. The important difference between this girl and my frightened friend is that Rosemary found an imaginative solution to the scary things that both she and my other friend know might be present in their worlds. But stories have given Rosemary ideas of ways to solve the problem.

The growth of a fluent imagination depends, like acquiring a new language, on practice and exposure. “There are . . . so many kinds of voices in this world,” wrote Paul, “and none of them is without signification.” I believe that if we listen to stories and read them out loud and expose our children to many of these different voices, our children will learn the language of imagination and become fluent in their ability to recognize the grains of truth hidden within stories and create their own and find brilliant new solutions to their problems. Then, with this ability, their own voices will not be without signification.

Part of learning a new language is becoming familiar with a new pronunciation and being able to recognize the sounds that, when put together, form words. Similarly, when a child acquires a fluency in imagination, he or she learns to recognize the stories that ring true and have a broader application to life. I like to think that developing a fluent imagination is really becoming familiar with that private place in the back of one’s mind by learning to recognize and become sensitive to some of the many faces of truth. I believe as we read to our children and share books and stories with them, and continue also to read and learn all our lives, both we and our children are acquiring more and more fluency in the language of imagination and creativity and recognition of truth and problem solving. These skills transcend culture and religion and the differences that spring up to divide people. People who have a fluent imagination become more adept at managing life in this world and in all the other worlds of imagination and reality around us. To develop this easy ability to imagine is one reason why we read and, in part, why we do anything—so we can communicate more effectively with the world around us.

.

I like this. Let’s give kids stories. All kids.