My Poems, Part 1

I had planned at this point to post a series of three installments presenting some thoughts of Orson F. Whitney, Merrill Bradshaw, and Clinton F. Larson; but with Dennis Clark’s reviews of my three books—Six Poems by Joseph Smith; First Light, First Water; and Glyphs (all published by Waking Lion Press)—in the recent past, and the release of my third collection of poems, Division by Zero (also by Waking Lion Press) in the near future, I beg to be indulged in posting a series of three installments on my own poems and how I came to write them.

In the summer of 1959, just after my freshman year of high school, I was an avoidant, introverted, intuitive, feeling fifteen-year-old with a rapidly developing thinking function living literally in a shack in the woods outside Anacortes, Washington, with my parents and three younger sisters, in relative penury, with two shirts and two pairs of pants to wear to school in town. I was seeking an identity and simultaneously sinking into a deep and nauséeux existential crisis (although those words did not come into my vocabulary until I was sixteen, when I bought an introduction to existentialism from the Cloven Hoof bookstore in North Beach). We were living, with a great sense of adventure and independence, my father’s dream of homesteading forty acres of fir, cedar, alder, salal, and huckleberry on a small lake that had come into his possession some years before. We were there through the four years of my high school career. Conditions were primitive. Our first shelter was a sixteen-by-twenty-foot army surplus tent, and my mother cooked our food on an open fire. We progressed to a shack walled with “half-rounds” from the local plywood mill, with the tent pulled over the top of the walls to serve as a roof, and later to a crude A-frame that I helped my father build on a foundation of logs. We never had running water (my oldest sister and I carried water in buckets from the lake), and for the first two years we had no electrical power or telephone, lighting our quarters with candles. I caught trout and bullheads in the lake; my father killed deer on the place (in season; he despised poachers), and it was necessary to shoo away bald eagles from the ducks that we had running loose during one of the summers. My father was employed in town at the plywood mill, and my oldest sister and I attended school in town, walking half a mile to the bus stop.

Those four years were spiritually and intellectually formative for me. My mother had been brought up in the Church of God in Texas and Oklahoma, and I had learned the Bible stories in the Sunday School of the Church of Christ (which I learned later was descended from the Campbellites of Sidney Rigdon). By the summer of 1959, however, I was in the depths of adolescent spiritual crisis. My father was college-educated on the G.I. Bill as a WWII navy veteran, and he was a philosopher in spirit. He had taught me when I was twelve the rudiments of logic and the importance of identifying the premises of my thinking, and I applied the principles in a spasm of ruthless Cartesian doubt to what I had been taught in Church of Christ Sunday School, and by the time I was fourteen I found myself staring with horror into the abyss. My father’s college text books and my mother’s “big dictionary” and Bible were the core of the family library, and by candlelight in the shack and sitting on logs in the shade of fir trees I searched world history and intro to philosophy texts for an answer, looking up words in the “big dictionary” and occasionally sampling the Bible. Before the end of my sixteenth year, I had been introduced in an elementary way to every major answer that has ever been proposed to the big questions—Why should I get out of bed? Why shouldn’t I murder my neighbor and take everything he has? Why shouldn’t he do the same to me? What can should possibly mean?—and, to every answer, I had to say, “How do I know that this is true?” and admit that I did not.

There was one enormously important break in the darkness that was enclosing me. As I said, I was looking for an identity, and I suddenly, unexpectedly discovered one that served for a time. Every Sunday morning, my mother sent me off the country grocery that was about a mile away from our woods to buy the Sunday paper. She preferred the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, but on July 2, 1959, the store had sold out the P-I and I took the Seattle Times. Looking at it later, I came on an article titled “North Beach Refugee: Beatnik Wars on Mediocrity,” featuring a young man named Jimmy Ginn, who was pictured bearded, with a scarf around his neck, holding a smoking cigarette, and who had recently become the manager of an art gallery on Pine Street, Seattle, called “The Subtle Game.” He was described as a refugee from the Beat community in North Beach, which had been overrun by tourists; as shod in beach sandals; as saying that he was “a Christian, first, last, and always” (though I have no idea what that could have meant to him). The combination of intellect, bohemian nonconformity, and some sort of spirituality was irresistibly compelling to me, and I said to myself, “I want to be him!” (Only years later did I catch the ironic fact that he had been brought up Mormon, and in my naïveté I had also overlooked hints that he was not heterosexual, as I most definitely was.)

I reasoned that if I was to be “him” I needed to know something about art. I was in the habit of walking the five miles into town to the little Carnegie Library and returning with several books (usually sci-fi, which served me as a literature of ideas at a time when I was desperately seeking an idea that worked). I made my next trip with the intent to find some books about art. In the library, a book that was displayed on top of a bookcase presented itself to me: How to Understand Modern Art, by George A. Flanagan. I picked it up, and the whole world of art and literature opened before me—it was stout Cortez staring at the Pacific.

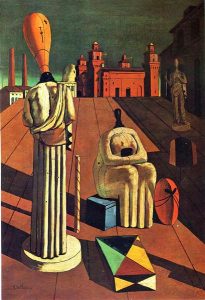

I was struck especially hard by the chapter on fantastic art and Surrealism. No one had ever told me about the existence of any of the art to which that book was introducing me, including works like those of Salvador Dalí, Giorgio de Chirico, René Magritte, or Meret Oppenheim. Here are some of the works represented, with links to sources of the images:

Melancholy and mystery of a street – Giorgio di Chirico

The Gates of the City, Nightfall – Eugene Berman (1937)

The Gates of the City, Nightfall – Eugene Berman (1937)

The disquieting muses – Giorgio di Chirico (1918)

The disquieting muses – Giorgio di Chirico (1918)

Fantastic Ruins with Saint Augustine and the Child – François de Nomé (1623)

[I was unable to copy in their entirety two of the most famous images: Object – Meret Oppenheim (Paris, 1936) and The persistence of memory – Salvador Dali (1931), because I could only save a segment — both are in the collection of MOMA.]

And then there was the poetry that was used to help explain the Surrealist art: excerpts from the Illuminations of Rimbaud and Young Cherry Trees Secured against Hares of André Breton (samples included at the end of this post). I had quite unexpectedly and abruptly stepped into a world of mysterious beauty, terror, and infinitude. Oppenheim’s furred tea set seemed to confirm my worst fears about a terrifying nastiness that might lie beneath the surface of the world, but in the world of “Après le deluge” there was ineffable purity and beauty, and both the infinite perspectives of Surrealist painting and the exquisitely lovely irrationality of Breton’s lines somehow reassured me that there was an infinitude in existence, that there existed a “sur-reality” beyond the walls big enough to include the conditions in which Rimbaud’s and Breton’s poems made perfect sense. That gave me an injection of hope. Soon afterward I discovered the existence of Howl (though it would be three years before I laid my hands on a complete copy, and by then I was in a different spiritual world) and of Jackson Pollock’s brilliant drippings. I had already been identified as a budding writer by my high school English teacher (on the basis of a description of the space-alien friend who was hiding out in my bedroom closet), and now it was quite clear to me that my destiny was to be a Beat, Surrealist poet.

But by early January of 1960, I had run out of spiritual energy. I was at the end. Even the world of art and poetry that I had discovered were not enough to keep me going. I never seriously contemplated suicide, but I had come to the point where I dreaded going to sleep at night and then waking up the next morning to the abyss. On a dark drizzly night I went outside the shack (by then the A-frame), and dropped to my knees on the ground at the edge of our clearing in the fir trees and prayed the agnostic’s prayer: “If there is a God, and there is some plan for this life, please tell me somehow, because I can’t go on like this.” I had no expectations, but as soon as the words were out I was struck within my breast by what I can best describe as an electric shock leaping from an unseen finger. I knew instantly that that was the answer to my prayer. Something, somebody, had heard and had responded. As I stood up, I realized that what I had felt as parts of my self pulling apart had just shifted noticeably back toward a center, toward a re-integration. There was a floor of hope under my feet. I walked about in the dark for awhile, thinking on what I had experienced, and then I stopped and looked into the overcast sky and said aloud, “I don’t know what the truth is yet, but I know now that there is a truth, and I will look for it until I find it, and when I find it I will do anything it requires of me.” I did not understand until many years later that I had just undertaken the covenants of obedience and sacrifice, and it would not be long before “true messengers” arrived with the next covenant. There was much yet to happen, including stumbling upon the first chapter of Mere Christianity and some more brief revelatory experiences, but despite my growing spiritual awareness my life plan in November of 1960 was to finish high school, which was working well for me, find my way to Venice, California, hang out in Beat coffee houses, take peyote, write Surrealist poetry, and consort with like-minded women. In November the Mormon missionaries came to us, and you could say that I was overcome by a vision on the road to Venice.

I take both my discovery of art and a literary vocation and my discovery of the restored gospel as providential, and I take it as providential that the discoveries came in that order, for, if the second had come first, what was the first may not have happened. Years later I told some of the story of my discovery of poetry to a BYU English professor, and he said, “You weren’t brought up in the Church, were you? If you had been, they would have washed all that out of you long before you were fifteen.”

There was another thread to my development that even now is still trying to find its place in the rope, that of “Indianness,” for want of a better word. My father, Raymond Douglas, was of Samish descent (the Samish were a once sizeable tribe of canoe Indians that claimed a large portion of the San Juan Islands and some of the mainland near them), and he was Indian to the bone. Among all the other he things he was, including sailor, war veteran, college graduate, school teacher for a time until he became disgusted with the politics and bureaucracy, he was also a woodsman, a deer tracker, and a canoe carver. We took pride in the Indian ancestry (and in the father that we knew was an unusual man), but, although he had close ties all his life to the local Samish and Swinomish people (served as the first Scoutmaster for the Swinomish when they sponsored a Scout troop in 1949 or 1950; I camped as a child with his Swinomish Scouts on “the forty”), and although he was invited to enroll with the Swinomish (but declined because he did not want it thought that he was taking undeserved advantage of benefits), he never encouraged us to identify as tribal. Late in his life he relented and enrolled with the Samish, but we were left to discover for ourselves that we were eligible to enroll and indeed would be welcomed back to the Samish people. I myself am now enrolled, as are virtually all of my father’s sizeable posterity, and participate as best I can in tribal activities from a thousand miles from home. When I, my siblings, and my children and grandchildren were given the chance to “choose sides,” there was no hesitation. That element of background has contributed to my deep sense of marginalization and alienation from the Church’s first host civilization, which it seems to me has become irredeemably corrupt and psychotic.

When I returned to high school for my sophomore year after that pivotal summer, I was all alive to what was contained in our literature textbooks. I was disappointed, however, because the “mainstream” works to which I was introduced there seemed superficial compared to what I had discovered on my own. All the devices of English prosody were ripples on a sea in which I wanted to plunge to the depths, and the way to the depths was through marvelous imagery. I have learned to read, enjoy, and admire the textbook poems, but they still are to me what “square” music is to the aficionado of jazz. After the likes of Rimbaud and Breton, I am still most comfortable with the likes of Kenneth Rexroth and Gary Snyder, and of David Gascoyne, who introduced Surrealism to England.

In my personal depths, I wanted to be able to call myself a poet, but that became a long deferred aspiration. Becoming LDS meant becoming super-responsible. I won a journalism scholarship out of high school and started on the path into establishment journalism, which finally became a dead end. There would be a mission, military service, marriage, children, and the long slog of making a living, mostly in employment as an editor in the Church Curriculum Department. That was a great deal of distraction for someone who in the first place had possessed only a very slender lyrical gift. And I think something else was at work. Somewhere, T. S. Eliot wrote something to the effect that a revolutionary age seldom produces a great poetry because during a revolutionary age ideas must be held as believed rather than as felt. I suspect that religious conversion may have the same effect. For the first twenty years of my life in the Church I was much more concerned with theology than with poetry. What had held magic for me at fifteen lost its magic for a long while—the sci fi, the Illuminations, the poems of Breton. My life as a Mormon very nearly did wash all that out of me (though I must say that the wonders that I discovered in the restored gospel surpassed anything that I had found in sci fi).

Nevertheless, I continued to aspire to write. After I separated from the army in 1971, my wife persuaded me to transfer from the University of Washington to BYU. I had become deeply interested in psychology, and I entertained an idea of becoming a journalist specializing in behavioral sciences, and so I used two years of my G.I. education benefits getting a BS in psychology. I had hoped to do graduate work in psychology, but crashing and burning in a math class that was a prerequisite for stats, which were prerequisite for graduate school in psychology, foreclosed that path, and I no longer saw a path into journalism. The job market in 1973 was not good, and it made the best financial sense for me to continue on as a professional student, making the most of the two years remaining of my G.I. benefit. I had taken a writing course from Dean Farnsworth during my first year at BYU, and one day I went to his office and told him that I thought I wanted to do some graduate work and that I thought I might do it in English. He said, “I think that is a marvelous idea, and I want to write one of your letters of recommendation, and since I am the graduate coordinator that means you are accepted. Now, go down to the composition office and apply for a teaching assistantship, and tell them I sent you.” After two years of course work, I was hired as a Church Curriculum Department editor, and three years later, after an exquisitely hellish experience of writing and rewriting a thesis, I finally took my M.A. in English, then remained in Curriculum Editing for seventeen more years, until 1995, when, with my wife’s blessing, I left employment in “the system” to be a full-time writer and researcher (or a bum supported by my wife; the line was thin sometimes).

In the next installment, I will talk about my poems and how they came to be.

Thoughts?

BY ARTHUR RIMBAUD:

AFTER THE FLOOD

*****As soon as the idea of the Flood was finished, a hare halted in the clover and the trembling flower bells, and said its prayer to the rainbow through the spider’s web.

*****Oh! The precious stones that hid,–the flowers that gazed around them.

*****In the soiled main street stalls were set, they hauled the boats down to the sea rising in layers as in the old prints.

*****Blood flowed, at Blue-beard’s house–in the abattoirs in the circuses where God’s promise whitened the windows. Blood and milk flowed.

*****The beavers built. The coffee cups steamed in the bars.

*****In the big greenhouse that was still streaming, the children in mourning looked at the marvellous pictures.

*****A door banged, and, on the village-green, the child waved his arms, understood by the cocks and weathervanes of bell-towers everywhere, under the bursting shower.

*****Madame *** installed a piano in the Alps. The Mass and first communions were celebrated at the hundred thousand altars of the cathedral.

*****Caravans departed. And the Hotel Splendide was built in the chaos of ice and polar night.

*****Since then, the Moon’s heard jackals howling among the deserts of thyme – and pastoral poems in wooden shoes grumbling in the orchard. Then, in the burgeoning violet forest, Eucharis told me it was spring.

*****Rise, pond:–Foam, roll over the bridge and under the trees:–black drapes and organs–thunder and lightning rise and roll:–Waters and sadness rise and raise the Floods again.

*****Because since they abated–oh, the precious stones burying themselves and the opened flowers!–It’s wearisome! And the Queen, the Sorceress who lights her fire in the pot of earth, will never tell us what she knows, and what we are ignorant of.

BY ANDRE BRETON, FROM YOUNG CHERRY TREES SECURED AGAINST HARES:

If a dishevelled woman follows you, pay no attention.

It’s the blue, you need fear nothing of the blue.

There’ll be a tall blond vase in a tree.

The spire of the village of melted colors

Will be your landmark. Take it easy,

Remember. The dark geyser that hurls fern-tips towards the sky

Greets you.

*****…The letter sealed in three corners with a fish…

A brazier was already yielding

In her bosom to a lovely romance of cloaks

And daggers.

He is coming and that is the wolf with teeth of glass

The one who eats the time in small round boxes…

I find myself interested by the similarities and contrasts in our experiences. Like you, I grew up in the Pacific Northwest, though a good decade and a half later, highly alienated from the dominant culture, and a geek who found something of a home in imaginative literature. Unlike you, I was raised as a suburban Mormon (lived in Eugene and various small towns), and never connected either to surrealistic art or to modern poetry. Maybe that was washed out of me by Mormonism? But fantasy in general and Tolkien in particular spoke to me at least as powerfully as you describe poetry and art as speaking to you. For me, the first real imaginative conflict was trying to reconcile my longing for fantasy worlds with the more prosaic demands that Mormonism made of me.

Which suggests an alternative narrative, or two, had you been born Mormon. Discovering that Mormon culture didn’t fill all the needs you felt you had, you might have then abandoned Mormonism for the art and literature that spoke to those parts of your soul. Or you might have tried to navigate the two. But it’s my experience that longings of the heart and imagination, while they may be drowned out for a space of time, eventually emerge.

Or a third narrative: that one discovers in the scriptures and in personal spiritual experience doorways to realms of wonder that are overlooked, or ignored, or even feared in Mormon popular theology and culture. (Or maybe that is an expansion on your second narrative.)