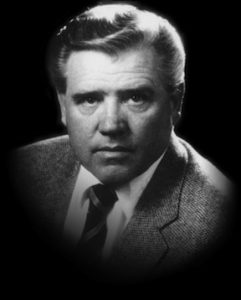

Beauty and Holiness: Merrill Bradshaw

Merrill Bradshaw set forth a philosophy of art in four statements: “The Articles of Faith—Composer’s Commentary” (BYU Studies, 3, Nos. 3 and 4 [1961], 73 – 85]); “Reflections on the Nature of Mormon Art” (BYU Studies, 9, No. 1 [1968], 25 – 32); Spirit and Music: Letters to a Young Mormon Composer (Brigham Young University Publications, 1976); and  “Music and the Spirit,” in Arts and Inspiration, Steven P. Sondrup, ed. (BYU Press, 1980). Brother Bradshaw picked up and developed themes first sounded by Elder Orson F. Whitney, primarily the existence of some connection between the arts and the gift of the Holy Ghost, and the contribution of the artist to the establishment and the life of Zion. Although he was primarily interested in music, most of what he said can be applied to literary art with the necessary adjustments.

“Music and the Spirit,” in Arts and Inspiration, Steven P. Sondrup, ed. (BYU Press, 1980). Brother Bradshaw picked up and developed themes first sounded by Elder Orson F. Whitney, primarily the existence of some connection between the arts and the gift of the Holy Ghost, and the contribution of the artist to the establishment and the life of Zion. Although he was primarily interested in music, most of what he said can be applied to literary art with the necessary adjustments.

**Brother Bradshaw first defined music as “movement in sound when it embodies the inner gestures of the human spirit” (Letters, p. 2), and then continued: “Our task as composers is to find the ‘hidden fire’ or the expressive contours of our spiritual impulses and embody them in sound…. The process consists of relating your sensitivity for sound to your sensitivity for the spirit” (Letters, p. 2). Lower-cased spirit there, I am guessing, refers to the human spirit, and he said in “Reflections” that “the inward nature of both prayer and the arts suggests that they are both basically human in their origin,” (p. 28), but he related the arts to the Spirit of God, speaking of “the parallel between artistic expression and ‘bearing one’s testimony’” (p. 28) and stating that “just as the need for prayer may be motivated by the strivings of the human spirit and the precise utterance of prayer inspired by the Holy Ghost, so may art be inspired; and the Mormon artist may properly seek the inspiration of the Spirit in his creative activities” (pp. 28 – 29). In one of the Letters, he wrote: “Be true to the Spirit…. Let it dictate both style and content” (p. 18). He wrote in another of the letters that the “fundamental task of the Mormon composer is “to find the Spirit of God and embody its expressive movement in your music so that performers who have the Spirit may give it life as they perform your music and listeners may be inspired with the love of eternal things” (p. 5) and that the greatness of works of art is to be measured by “the intensity with which they bring us face to face with the Spirit” (p. 4).

**Although Brother Bradshaw saw a possibility that art could be a kind of bearing of testimony, he saw that as being more than a “propaganda” function (“Reflections,” p. 28). He observed that “the function of the arts in the Restored Church is suggested by [D&C 82:14]: ‘For Zion must increase in beauty and holiness,” that “the idea that the arts as the embodiment of beauty can have a profound spiritual value is one most of us have instinctively recognized,” and that “the suggestion that the arts might function parallel to the increasing of holiness in Zion seems to place the artist in a more acceptable relation to the activity of the Church than does the present commonly held idea that art serves only a propaganda function,” for, he went on to say, ”holiness is something that is achieved not through propagandizing but through inspired effort towards perfection, which effort is both encouraged and epitomized in the masterpieces of great art” (“Reflections,” p. 28). One of the tasks of the artist “is to inspire [his audience] with insights into eternal things” (Letters, p. 6). It is here, ultimately, in the experiences of the Spirit and the insight into eternal things that the Spirit gives, that Brother Bradshaw placed the “Mormonness” of Mormon art. He advised young composers: “To accomplish your task…. You must live so that you can feel the movement of the Spirit in your heart. What you do in music will always betray what you are…. Consequently you must become so attuned to the eternal that you live in, for, and by the Spirit…. Your ‘Mormonness’ must become the fundamental impetus of your creative activity. (Mormonness means your Mormon view of eternal things)” (Letters, p. 6).

**Letting the Spirit “dictate both style and content” will not, according to Brother Bradshaw, result in uniformity of artistic creation. In “Reflections” he said: “I suspect neither God nor the Church would want to make sincerity impossible by prescribing what one should pray or sing or paint except in the most ceremonial situations. Thus we are left to decide for ourselves artistic principles that seem logical within our culture and consistent with what we individually wish to express” (p. 28).

Brother Bradshaw suggested that the Mormon artist has a special interest in the styles of many eras and cultures. He observed that the Mormon idea of the “dispensation,” the belief that “history has been punctuated with repeated heavenly affirmations of basic principles of action and belief,” is a concept that “brings the Mormon artist into direct theological contact with several periods of world history not only in the developmental, evolutionary sense that the age to age chain of their thought has provided some of the roots of our system, but also in a nonevolutionary sense that affirms certain principles as unchanging and allows certain ideas to leapfrog over the various stages of cultural-historical development” (p. 29). Since the patriarchs and the prophets are our brethren and are directly inspired of God, “the details of their way of life and thus the cultural systems in which they lived become significant to us” (p. 29). Furthermore, “the extension of this way of thinking to historical periods not directly involved with the dispensations, and to influences from other cultures, opens up wide vistas of style and technique” (p. 29). He continued: “The point is quite defensible that art has taken different forms in the different dispensations and that in this, the ‘dispensation of the fullness of times’ when all things are to be gathered in one,’ influences from all of these past forms of art are legitimate and important” (p.30). The concept of the gathering of all things in one during the final dispensation suggested to Brother Bradshaw “another direction, involving the tendency of Mormon thought to reconcile opposites so that they might exist in the same system.” He reasoned that “in the artistic realm the mere acceptance of influences from the various epochs and styles…becomes insufficient,” for “the Mormon artist has the responsibility of bringing these styles into a system where their divergent, conflicting characteristics are balanced against each other in single, dynamic, unified manner of expression” (p. 30). He said that he was not talking about “a simple eclectic combination of styles into an unintegrated stylistic hash,” but rather “the creation of a true synthesis of these many facets of his [the artist’s] experience into a unified, integrated expression of his culture, his thought and his deepest, most precious possession, his testimony” (p. 32).

Brother Bradshaw also had things to say about the relationship of art to emotion and of the artist to his audience, but I am trying here to stay close to a theme. Of course, given my initial premises, I applaud his definition of art in essentially formalistic terms of “unity” and “style”—a large step forward, I think, toward something that Elder Whitney may have dimly glimpsed. I quibble with the Romanticist language of “expression,” for reasons I have already explained (and I am going to insert a thought here that deserves further development, that so long as Restorationist writers think of their job as the “expression” of something, they will tempted to propagandize and to succumb too quickly to pressures to propagandize), but I think he is on the mark in emphasizing the importance of style, though not as a means of expression, but rather as one technique of the process of discovery that is artistic creation. The idea that Restorationist artists have good reasons for taking interest in the styles of the artists of past dispensations (I don’t see how we can get away from the centrality of both the Bible and the modern scriptures to our apprenticeship as writers) and of all the world’s cultures strikes me as very important (for one thing, it should give comfort to artists who are sensitive about having some particular style imposed upon them). Brother Bradshaw did not, so far as I know, suggest a particular style as being particularly analogous to revelatory experience; that suggestion (and I have said suggestion; not trying to impose anything on our artists) was one of Clinton F. Larson’s contributions, to be considered in the next installments.

**Thoughts?

I particularly like what Bradshaw has to say about multiple styles (based on your summary), though I’m perhaps a little more Bakhtinian in not seeing synthesis and integration as the necessary goal. I’m more inclined to think that a drive to synthesize may prematurely cut off development of those different impulses, in creative tension with each other, from which a true synthesis may emerge.

Which leads me to wonder if the “system” Bradshaw talks about might more productively be considered as the body of Mormon art (or the world’s art) as a whole, rather than any particular artist’s production. Might we not creatively expect all good and virtuous art ultimately to be circumscribed into one great whole? Which makes me less inclined to privilege particular artistic/creative sources (even the Bible and the scriptures) over others, and more inclined to see how the work of different Mormon artists plays out.

I also can’t help but think that perhaps the work of the critic in Zion is as much to help redeem the world’s art by pointing out its value in a Zion context as it is to encourage the development of worthwhile art by Mormons. It’s a very large field, and plenty of space for all of us to swing our sickles, no matter where we may find ourselves to be.

{{I also can’t help but think that perhaps the work of the critic in Zion is as much to help redeem the world’s art by pointing out its value in a Zion context as it is to encourage the development of worthwhile art by Mormons.}} I am with you there. And I am sure that Merrill Bradshaw and Clinton Larson would agree also.

A senior ecclesiastical leader observed about 40 years ago that he did not believe that anything of the “glory” of the Restoration could be captured in a rock-and-roll idiom; Larson’s answer was “Who is he to say? That’s a question for the artist to answer by what he creates.” And I think that Bradshaw’s “synthesis” is as opposed to mere imitation–“make it new.” What Bradshaw has done is open up the whole world of art and infinite possibilities of artistic creation to the Mormon artist and and the Mormon audience, while urging that we remain in touch with the tradition of the Dispensations. Makes sense to me.