Valerie and I have been travelling through Canada, crossing the border at the Port of Roosville, north of Eureka, Montana, and driving through Kootenay, Banff and Jasper National Parks for most of a week. On our last day in Jasper, we stopped at two waterfalls, Sunwapta Falls on the Sunwapta River, and Athabasca Falls on the Athabasca River. The Sunwapta is fed by the Athabasca Glacier[i] , and eventually flows into the Athabasca, which is fed by the Columbia Glacier[ii]. Both glaciers are part of the now much diminished Columbia Icefield in the park[iii].

The falls are fascinating because both rivers, which are wide, swift, cold and turbulent, squeeze through rock crevasses which seem far too narrow to admit the volume of water passing through them. At Sunwapta, for example, the massive rock-flour river plunges through a gorge maybe 15 feet wide, at least 30 feet below a bridge spanning the gorge.

This is a picture of the head of Sunwapta falls, and it is impressive enough that a river that wide and turbulent is plunging into this gorge. It could be a very wide but shallow river. This, however, is the wide part of the gorge, and it was impossible for me to determine how deeply the river has cut into the rock. But the next photograph is the narrow part of the gorge:

That is looking down from the upstream side of the bridge, at the narrowest part of the gorge. Squeezed through this gorge, water hits a rock wall where the river makes a 90º turn, hard to appreciate without sound, but try to imagine a conversation where everybody is shouting and no one is listening:

I do not recall any interpretive signs at Sunwapta Falls; if there were, I didn’t shoot them. So that may be why I started reading closely those at Athabasca Falls. It’s possible to interpret the Falls as God’s poem, with the roar and spray the reading of the poem. I would be comfortable with that. But this is what the Jasper National Park staff wrote for the first sign, the introduction to the falls and a thematic assessment of them, as it were, transcribed verbatim from my photograph but arranged in what often passes now for lines of verse:

Athabasca Falls

Since the last in a dynasty of glaciers retreated 10,000 years ago,

the Athabasca River has battled a trembling earth.

Abandoned channels, potholes and deep canyons

in some of the hardest rock in Jasper National Park

mark the ancient battle lines. Today, the battle continues

upstream at the 25-metre falls.

This trail offers a 20-minute visit to one battleground

in a land of many. It is a dangerous place,

so please stay behind the guard rails.

Okay, so the controlling metaphor is one of war, after the fall of a dynasty, between two factions previously held in check: rock (“some of the hardest rock” around), and the river. Rock and the River. Good title. Now I realize that no one writing these interpretive signs was trying to write poetry, but in choosing a theme and finding a controlling metaphor, they were coming close. And I realize that none of them will read this critique. But for you, I want to explain why this kind of promotional writing is bad poetry. For example, “the Athabasca River has battled a trembling earth” sounds like it’s invoking vulcanism or the uplift of the Rocky Mountains, but that was even further in the past than that “dynasty of glaciers.” And the only example given of “a trembling earth,” and the focus of this battle, is “some of the hardest rock in Jasper National Park.” If you choose to focus the metaphor like that, you’ve contradicted yourself without invoking a paradox. And as we see in this next poem, the rock loses:

Abandoned Channel

Flowing water relentlessly battled the bedrock

carving this channel. Later,

water found a break elsewhere in the rock’s defenses —

this channel was forsaken.

In a battle, you don’t forsake your enemy; you kill them, or take them prisoner, or make them citizens of your empire (if you are Rome). In the pictures I took of this scene there are two abandoned Styrofoam cups, one in the forsaken channel and one on its lip. I couldn’t retrieve either one, because of this dangerous place. This channel, which was maybe a metre wide, had been not abandoned but bypassed. Our next poem examines the battle in detail:

Potholes

Trapped and spinning under water’s direction,

particles of sand, silt and gravel carve like a diamond drill.

The river took thousands of years to drill the potholes

now suspended on the canyon walls.

The potholes you see forming today

will one day be suspended

on the walls of an even deeper canyon.

Nice play on the word “suspended.” But these potholes are like that one being drilled where Sunwapta Falls hits a wall and turns 90º. They are alcoves. And if the river took thousands of years to drill the potholes, it was not using any diamond drill-bit I’ve ever seen. But at least here the battle metaphor is suspended, and a metaphor much closer to the processes at play is brought in. By its nature, a pothole will always be broken when it’s not forming, unless it becomes a pothole arch, instead of just another sensuous curve in the wall.

Remember what I said about rock losing? Here is a bit of frank imagery:

Rock’s Retreat

A few thousand years ago,

the lip of the waterfall was here,

beneath your feet.

Under the river’s constant attack,

the rock lip has eroded back to the head of the gorge —

today’s battle front.

Where to begin? One does not retreat by charging headlong into one’s foe. And the head of the gorge has a rock lip? Unless the gorge is very skillfully girning, that would imply that the water is pouring out of the mouth of a rock head — which would be an interesting image, if intentional. But here’s what the lip head looks like:

If it weren’t for the head of the gorge and the lip of the falls, you could talk about battlements here — or redoubts and the fog of war. But even that would not help a strained metaphor. What we have here is a long slow grind. Or perhaps river tripping over rock and falling on its face. “I have fallen, and I can’t get up.” So the next entry should be no surprise:

Battlefront

Water fights the rock lip back

a few millimetres a year.

Now, the water is winning

but the nature of the rock

may one day force the water

to abandon this channel

and seek another route.

Since when does “the nature of” the enemy force its foe from the field of battle? Here, it would seem that we have entered a world where rock retreats by advancing upstream, and water advances by retreating. Water may win by wearing the rock lip back, but in fact it is the obdurate nature of the rock that forces the water into a channel far too narrow for it, as at Sunwapta Falls. So in the next, and final, of these interpretive poems, “the nature of the rock” may in fact “force the water to abandon this channel”:

Time Tunnel

After centuries of battle, the waters surrendered

and abandoned this channel.

Walk back through time and imagine the struggle

between rock and water.

Here the rock won but the scars of battle remain.

What happens here is that a trail goes down to the river, where it leaves the present gorge, through a former channel. In hiking down the trail you’d be walking backward in time; in hiking up, you’d be returning to the recent times. But I’m not certain that this was the former channel for the entire river, any more than that abandoned channel was. The present channel is far deeper than this trail, and the water may just as well have worn away an obstacle diverting part of the water into this channel. The metaphor of battle doesn’t fit what is going on at Athabasca Falls any more than it would fit at Niagara Falls. As I walked down the trail a girl was posing with her hands over her head, braced against the roof of the former channel as if holding it up, and trying to instruct her mother — in French — on how to take the picture. I think that playful spirit fits the events more. So I am going to present here a poem I wrote about a similar situation, called “Water & Rock”:

What Rock Says to Water

Stay. Stop and play.

Please be still.

Wait a week. Keep me wet.

Stand in the sand. Stay with stones.

I look in your face and find my own.

Back when I flew, we danced and flung

ourselves against an older ground,

picking, flushing, scraping, prying.

That was before I settled:

shallow sea, sandy bed.

Wait at the foot of this wall. Pool.

At bedrock lie and braid with me.

water answers

i’ll warm with you, and you

come run with me

leaping boulders

i’ll be tears for your face

while it thaws

we can hip-hop to the sea

grinding stones, flinging logs

we’ll cut our way through

the sad sediments

scour the graves

scoop out and roll the old bones

when I leave you sunk with them

in a bowl of slick rock

don’t sink too deep

i’ll be back and we can flee

further, a little further

That, of course, is written about a far more sedate landscape, the deserts of southern Utah, and in the hopes of accurately describing what I see there. It was inspired by true potholes in Capitol Gorge, in Capitol Reef National Park, potholes filled with frog spawn, or frogs, depending on the season.

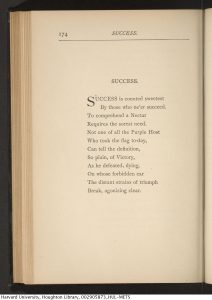

So all those strained metaphors above contrast with the last two of Emily Dickinson’s poems to be published in her lifetime, and even though their publication happened apparently without her knowledge, the publication shows that they, though not she, were not unacknowledged by her contemporaries. This is the ninth of them, and its publication is very ironic in that it put her in the position of having succeeded. It was first published in Brooklyn Daily Union, New York (April 27, 1864), then republished in the book A Masque of Poets (Boston : Roberts Bros., 1878, from which the image below is taken). This is her only known publication in a book during her lifetime. The poem, as published, was of course altered. The alterations in words are shown below, italicized in square brackets, to make it a little easier for you to identify them. The alterations in punctuation and capitalization are not shown, but you should be able to find them on your own by comparing this text with the image shown below.

Success is counted sweetest

By those who ne’er succeed.

To comprehend a nectar

Requires sorest need. [“the” inserted before “sorest”]

Not one of all the purple Host

Who took the Flag today

Can tell the definition

So clear of victory [“plain” replaces “clear”]

As he defeated – dying –

On whose forbidden ear

The distant strains of triumph

Burst agonized and clear![iv] [Break, agonizing clear.]

So the poem was edited, and I would guess that since the editor of the volume did not know who the poet was, and thus may not have known her, he[v] took the liberty to tidy up what was an anonymous newspaper poem that he liked.

I didn’t know who “all the purple Host” were, but on the same site as the image below, there is a lexicon of every word used by Dickinson. This is what it says after defining the word purple: “Phrase. ‘Purple host’: iris flowers; flags, in the botanical sense; [fig.] blood-stained soldiers; bruised battle-worn exhausted army personnel; brave heroic bold soldiers with flags, banners, or pennants.”[vi]

I found an image of the poem on its page[vii] as reprinted in the book; I don’t know what it looked like when first published in Brooklyn Daily Union, New York (April 27, 1864):

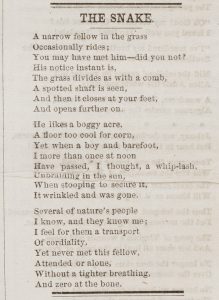

And the poem that may have put her off publication, the only one that I have found her to comment on, and the last published in her lifetime, was this one [again, I have indicated with bracketed italics differences in the published version from this version, including punctuation]:

A narrow Fellow in the Grass [fellow and grass]

Occasionally rides – [- replaced with ;]

You may have met him? Did you not [You may have met him—did you not?]

His notice instant is – [- replaced with ,]

[no stanza break]

The grass divides as with a Comb – [comb,]

A spotted Shaft is seen, [shaft]

And then it closes at your Feet [feet,]

And opens further on – [- replaced with ,]

He likes a Boggy Acre – [boggy acre,]

A Floor too cool for Corn – [floor ; corn,]

But when a Boy and Barefoot [Yet for But; boy; barefoot]

I more than once at Noon [noon]

[no stanza break]

Have passed I thought a Whip Lash [passed, I thought, a whip-lash,]

Unbraiding in the Sun [sun,]

When stooping to secure it [it,]

It wrinkled And was gone – [and ; gone.]

Several of Nature’s People [nature’s people]

I know and they know me [know, ; know me;]

I feel for them a transport

Of Cordiality [cordiality]

[no stanza break]

But never met this Fellow, [Yet for But; fellow]

Attended or alone [alone,]

Without a tighter Breathing [breathing,]

And Zero at the Bone[viii] [zero ; bone.]

First published in the Springfield Daily Republican, (February 14, 1866), under the title “The Snake”, this is what it looked like[ix]:

With one exception, that seems to me a perfectly competent editing job. When I was poetry editor of Sunstone, I might have edited such an eccentrically-punctuated poem about like that. The exception is the one Dickinson complained to Higginson about, which I discussed a year ago. But, as I had pointed out in my post of the month prior, the two primary editors of Dickinson’s poems, Johnson[x] and Franklin[xi] , disagreed on the word “instant” (Johnson had it as “sudden”).

So, what we have to hand here is the necessity of not just publishing the unpublished poems, but establishing the text to be published. Miller has, I think, done a fine job of that, and as the third in a line of editors she has stood on the shoulders of giants.

I will next take up the question of how three Western writers — Pound, Eliot and Frost — brought in a new poetry for the new century. Whitman and Dickinson were to have their greatest influence on the generation that came after those three. Like all Westerners, they and their families came from somewhere else (that is true of even the American Indians, but considerable earlier.)

But hold on, I hear you say: You’re abandoning Dickinson?

Your turn.

_______________

[i] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sunwapta_River, accessed 24 August 2016.

[ii] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Athabasca_River, accessed 24 August 2016.

[iii] Ibid., and personal observation, and many interpretive signs in Jasper National Park.

[iv] Emily Dickinson’s poems, as she preserved them / edited by Cristanne Miller. Cambridge, Mass. : Belknap, 2016.

[v] Lathrop, George Parsons, 1851-1898, ed. A masque of poets. Including Guy Vernon, a novelette in verse. Boston, Roberts brothers, 1878. 72S-700. Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.

[vi] http://www.edickinson.org/lexicon, accessed 24 August 2015.

[vii] The image can be viewed at http://iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:43434190$180i, accessed 24 August 2016 thru http://www.edickinson.org/resources#published-in-dickinsons-lifetime

[viii] Miller, Op. cit., pp. 443-444.

[ix] http://www.edickinson.org/assets/static_pages/The%20Snake%207268_1866Feb14_0001-14dc5c2751bc7c6285e994b057b35da3.jpg

[x] The poems of Emily Dickinson : including variant readings critically compared with all known manuscripts / edited by Thomas H. Johnson. — Cambridge, Massachusetts : Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1955.

[xi] The poems of Emily Dickinson / edited by R.W. Franklin. — Variorum ed. — Cambridge, Mass. : Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1998.

I’m an inexperienced poet. I found this delineation of why the commentary on the signs sounded corny, to be very helpful. I can read something and wince, but not know why.

I’m trying to decide if there is such a thing as “bad” poetry, though. Poetry is such a diverse attorneys, and always has been wildly experimental. Perhaps a better term is, “impactful” poetry. Vs…not impactful 🙂

I don’t know why your second post, correcting “attorneys” to “art,” didn’t show up. But I appreciate the comment. I call this blog “in verse” because I want to focus on verse rather than poetry. The distinction is that between a musical score — verse, in this instance — and a performance of the score — poetry. I believe that all poetry should be read aloud by the reader, because only when voiced does the text transcend verse. But that does not mean that all texts are worth reading — or worth hearing.

I didn’t talk much about Dickinson’s verse in this post because I’ve been doing that for over a year now. Dickinson was wildly experimental in her syntax, in her use of ellipsis, in compression; and, in her metaphors, very inventive. But she was fairly traditional in her verse, using hymn meters rather conventionally.

But I was interested in those signs because they seemed to me such fine examples of bad poetry — especially when read aloud. And I can’t agree with you that “Poetry … has always been wildly experimental.” One of the things I’ve discovered in writing the blog is that English verse has always been quite conservative, and that the conventions of iambic verse, which come into English in Chaucer’s time, duked it out for about 200 years with the alliterative tradition that came before, going back at least 700 years. The iambic conventions only won the day as the Tudors, a Welsh dynasty, came to power. And they only held sway for about 400 years before the American trio of Pound, Eliot and Frost started to take them apart.

Speaking in broad generalities, Blake was wildly experimental, and ignored in his lifetime. Whitman was wildly experimental and widely derided in his lifetime. Dickinson was wildly experimental, and none of her editors would publish her poems as she left them — until Franklin in 1998. Even Johnson in his otherwise fine variorum edition (1955) followed some of the earlier editors, rather than ED.

Even the poem I eventually made out of parts of this post is very conservative, in the idiom of 20th-century verse:

Rock and the River

The text of this poem is rock, some of the

hardest rock in Jasper National Park.

The voice of the poem is the Athabasca, newly

released, freed from the Columbia Glacier and wed

with the Sunwapta — ‘turbulent water’ joined

where ‘there are plants, one after another’ —

and so deeply entwined are the couple, they shoot across

the quartzite into a gorge of softer limestone

and tumble, shouting thanks for rubbing their backs

and scratching back to roars of approval.

The reader is God who sprays the audience over

and over, having set the poem on repeat.

This was my attempt to counter that bad poetry, and I worked almost entirely with the metaphor, rather than with the verse, which is still fairly iambic.

Anyway, thanks for your comment. Keep writing verse — its the only way for an inexperienced poet to gain experience. And write it in your own voice — it has far greater impact that way.

Thank you!!

You’re more than welcome. Thank you for commenting.

Finally got a chance to read this. (I’ve been busy with work deadlines.) At first, I thought you were possibly going to use the constriction of the water as a metaphor for how poetry condenses meaning, adding power to words by constricting the channel through which they flow. I’m still somewhat attached to that notion, though I also like what you did with the signs. (Speaking of which, have you ever walked by the Strid in Yorkshire? Another case of dangerously compressed water, though in that case it looks far less dangerous than it is.)

Interesting generational take: truly innovative poets often influence not the poets that follow them, but the generation after that.

Does Hopkins have a place in the account you’re telling? I ask because it seems to me that he is just as innovative in his own way as some of the others…