Back in 1984, I hitched a ride with a bunch of other BYU students and a professor or two to Worldcon, which was being held in Anaheim that year, right across the parking lot from Disneyland. A starving student, I didn’t have much money for souvenirs, but I had to buy something. After all, it was my first convention! So I got a bright yellow pin with the words “Born Again Druid,” and happily wore it all around the BYU campus after I got back. Because, you know, I was a tree-hugger from way back (being from Oregon and all), and so it was entirely appropriate. Right?

Back in 1984, I hitched a ride with a bunch of other BYU students and a professor or two to Worldcon, which was being held in Anaheim that year, right across the parking lot from Disneyland. A starving student, I didn’t have much money for souvenirs, but I had to buy something. After all, it was my first convention! So I got a bright yellow pin with the words “Born Again Druid,” and happily wore it all around the BYU campus after I got back. Because, you know, I was a tree-hugger from way back (being from Oregon and all), and so it was entirely appropriate. Right?

It is, I suppose, to the credit of BYU that although I got a few odd looks, no one ever took me to task for the message. It wasn’t until years later —after I had graduated from BYU, I think — that it occurred to me that my pin might, you know, be interpreted as a slam on Christianity. Or a genuine declaration of pagan belief. And that it was probably intended to be read that way.

(Pause here for headshaking at the naive little Mormon kid.)

The fact is, it’s not at all hard to find neopagans in fantasy circles. If anything, fantasy literature seems tailor-made as a faith literature for animism. The oddity, arguably, isn’t that some Christians have a problem with fantasy literature — but rather that so many of us don’t. Including an awful lot of Mormons.

#####

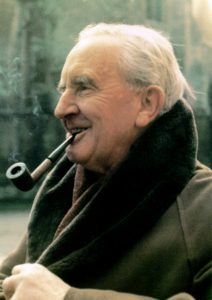

One of the primal desires behind the fairy-story as a genre, according to Tolkien, is the desire to hold communion with other, nonhuman living beings — such as trees. And so in The Lord of the Rings we have the Ents, and the Huorns, and the inhumanly wicked Old Man Willow.

One of the primal desires behind the fairy-story as a genre, according to Tolkien, is the desire to hold communion with other, nonhuman living beings — such as trees. And so in The Lord of the Rings we have the Ents, and the Huorns, and the inhumanly wicked Old Man Willow.

(And yes, Tolkien was also a devout Catholic.)

It’s not like we actually believe that trees have spirits, and can talk, and choose between good and evil, and twist their roots around to drown unwary Hobbits. Right? Right?

#####

Back when I was a graduate student working at an educational software company, one of my co-workers in the editorial department (also a student at BYU) found it very odd that even though I was a science fiction fan, I had no interest in the UFO stories that so fascinated him. He couldn’t understand how I could like fiction about spaceships without getting excited about real (or “real”) stories about spaceships.

I’ll pass over for the moment my sense that science fiction fans are likely to be more, not less, skeptical about such things (having a fair sense of what the rules of evidence are in science, famous exceptions such as John W. Campbell’s endorsement of scientology notwithstanding). The point is — again echoing Tolkien — that primary-world belief is not, in fact, necessary in order to enjoy reading about something in a story. We are safe to enjoy the story precisely because we don’t think it can happen in the real world.

This, by the way, is one of the mistakes some theorists of the fantastic make in talking about modern fantasy literature. The fantastic, for Todorov and Rabkin and those like them, is a zone that upends our sense of what is real and leaves us uncertain about the rules of everyday reality. But modern fantasy isn’t like that, by and large. Instead, it invites us into worlds which are explicitly not our own, where nothing that happens can affect us.

At least, that’s the lie we tell ourselves. But if, as Tolkien writes, fantasy is not about believability but rather desirability, what does it mean that some of us apparently desire with a deep, ardent desire to spend time in a reality that is ostensibly not our own? And what does it do to us to spend time there?

Thank you, Jonathan. This line really spoke to me:

Conversely, it is also why we are NOT safe—and exhorted thusly—enjoying stories from the real world because they can, do, and will, and stay away lest they happen to you, too or, worse, that you are tempted to make them happen.

I feel like exploring realms of possibility actually enhances faith…it rips open the ceiling of incredulity and frees us to think metaphorically and symbolically. The veil between the concrete and the amorphous becomes thinner, and our sixth senses–our spiritual receptors– sharper.

There was a really interesting exchange one of my lit professors had with a student when talking about fantasy. Both were pretty pro-fantasy (this was a class on Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, and George MacDonald). The student opined that fantasy was a distorted version of our reality which allowed us to explore things in a way we can’t while still “here.” The professor responded, “I agree, but I’m not convinced it isn’t our reality that’s the distorted one.”

“or, worse, that you are tempted to make them happen.”

That’s why the some of the worst stories are utopian stories that aren’t meant to be only fictional thought experiments.

Ah, but when you are reading, you are dealing with the working memory which has a very limited capacity. And so those other-world stories that you are reading are as believable as our own–in the moment of reading. If they aren’t, you get the UFO effect you mention above.

Fiction doesn’t work–it doesn’t provide the ride we seek–unless we believe it in the moment of reading. It doesn’t because our own bodies produce the emotions we seek, and we won’t produce them if we don’t believe the assessments of what’s happening to be real.

BTW, I’m not talking about a willing suspension of disbelief. There is no such thing in reading. Not when it’s working. You don’t willingly (consciously) suspend disbelief. What happens is that you read, the events fill the mind, and there is no room in that tiny working memory apartment for anything but what’s going on before your eyes. 🙂

John may or may not be right about the paucity of working memory, but I think it’s definitely right that we get involved in the world in the moment of reading. My sense of it, coming from many years of losing myself in books, is that the book itself has to sustain that world, because I, at least, cannot read through most books at one sitting. You know, family, food, going places, doing things with real humans, all interrupt. So if you can’t pick up the book and almost immediately slip into the story, it doesn’t happen.

That’s my experience right now with reading *To kill a mockingbird*. Not widely admitted to be a fantasy, but still fantastic.

It’s my understanding based on prior reading that brain theorists believe that we assimilate new knowledge with our existing body of knowledge by relating what we encounter to schemata held in long-term memory. So while it may technically be true that our short-term memory provides a limited-space window what we are currently reading, this is done in a context that is created by our prior understandings about the text — including memories of prior events (per Dennis’s comment) and our meta-understanding of its relationship (or non-relationship) with the real world. In short, I think there really is a difference in how we read different kinds of narratives, depending on our framing assumptions/observations/conclusions about the narrative.

Jenefer Robinson summarizes how emotion is generated while reading in her fabulous book DEEPER THAN REASON: https://www.amazon.com/Deeper-than-Reason-Emotion-Literature/dp/0199204268.

As for the working memory limitations, the research is everywhere. 3-5 chunks of information. 2-4 when you have to manipulate them.

You can see this limitation at work when examining writing that is vivid and clear and writing that is not. For an introduction see the videos linked to here: http://www.johndbrown.com/vivid-and-clear-video-and-audio/ .

Here’s another manifestation of this discovered by the military: http://www.infogineering.net/writing-clarity-rating.htm.

Clear writing depends on two things–(1) the vocabulary match between the text and the audience, which is driven by the reader’s background knowledge about the topic, and (2) the stylistic techniques an author uses. And the techniques that lead to clarity are mostly nothing more than ways of writing that better accommodate our working memory limitations.

Aside (in reference to multi-syllabic words): A Linguistic Analysis Of Donald Trump Shows Why People Like Him So Much

That was fascinating. Especially after just listening to this Radio West interview of David Crystal on eloquence: http://radiowest.kuer.org/post/how-eloquence-works-0