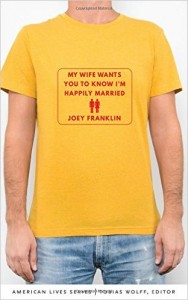

Joey Franklin was the winner of the 2015 AML Creative Non-Fiction Award, for his essay collection My Wife Wants You to Know I’m Happily Married (University of Nebraska Press). Today we present an interview with Franklin conducted by Elizabeth Tidwell, a fellow BYU faculty member.

Joey Franklin was the winner of the 2015 AML Creative Non-Fiction Award, for his essay collection My Wife Wants You to Know I’m Happily Married (University of Nebraska Press). Today we present an interview with Franklin conducted by Elizabeth Tidwell, a fellow BYU faculty member.

The essay as a creative rather than academic genre can be a foreign concept to some—we’ve often heard “essay” more connected to the five-paragraph essay than the personal essay. But that’s steadily changing as the genre is growing. You’ve just published your first collection of essays, so you’re clearly invested in the form. Why the essay?

I took a fiction class in graduate school and wrote three stories. The first was about a handyman who discovers that a widow in his apartment complex is actually a white-collar criminal. The second involved a disgruntled member of the Japanese mafia who shakes down a local pre-school. The third followed a pregnant Arab woman on a plane who stops a schizophrenic passenger from attacking her (none of those stories ever made it out of workshop). My professor knew I had kids and he knew I’d written a lot of nonfiction about my family, and so one day he called me into his office and asked me why I wasn’t writing more fiction about family life. The question helped me articulate for the first time why I write essays: If I have a question about my life, about my marriage, about being a parent, a neighbor, a human being—I want to address those questions directly—personally. And the essays is, for me, the most direct literary way to do that. For me, if something really matters, I’m going to essay it. The essay feels honest. It feels therapeutic. It invites me to learn more about myself, to think more critically about who I am and how I see the world. It encourages me to be more empathetic. More curious. More authentic.

Did you have an “aha moment” when you identified yourself as an essayist? How did you come to the essay?

I’ve been writing essays since high school, but mostly without realizing it—journal entries, letters, personal narratives, blog posts—but the first time I encountered the genre by name was in Jane Brady’s freshman English class at BYU. I’d just gotten married and wrote a piece about how my wife and I met, but I didn’t want to write the same old courtship narrative. So I used a bunch of Shel Silverstein poems and braided them together with some narrative and reflection on the dating process at BYU. I remember having the entire floor of our tiny basement apartment covered with scraps and fragments of text as I tried to arrange the essay. The final product wasn’t the best thing I’ve ever written, but the essay process—from initial drafting and exploration to the fine tuning of sentences that are meant to explain a small bit of one’s life—I fell in love with it. I think I like the challenge of taking something mundane from my own life and writing it in a way that a complete stranger might enjoy.

I’ve been writing essays since high school, but mostly without realizing it—journal entries, letters, personal narratives, blog posts—but the first time I encountered the genre by name was in Jane Brady’s freshman English class at BYU. I’d just gotten married and wrote a piece about how my wife and I met, but I didn’t want to write the same old courtship narrative. So I used a bunch of Shel Silverstein poems and braided them together with some narrative and reflection on the dating process at BYU. I remember having the entire floor of our tiny basement apartment covered with scraps and fragments of text as I tried to arrange the essay. The final product wasn’t the best thing I’ve ever written, but the essay process—from initial drafting and exploration to the fine tuning of sentences that are meant to explain a small bit of one’s life—I fell in love with it. I think I like the challenge of taking something mundane from my own life and writing it in a way that a complete stranger might enjoy.

This collection is a delightful read. For me, a lot of the pleasure comes from the depth of insight and the balance of your experience with the universal human experience. But there’s also a generous helping of humor that keeps us coming back for more and more. Humor is notoriously tricky to write, but comes across as very natural here. But not all of your essays rely on humor—they are full-bodied, thoughtful pieces. Tell us about what this looks like behind the scenes for you. How do you know when you’re striking the right tone for a given essay?

I think I have the most success when I don’t take myself too seriously. I think my natural instinct is to write sappy hallmark cards and bad sermons, so I have to work hard against that. So I try to be self-deprecating, to confess my own foibles, to play on the page a bit, to undercut my own nauseating sentimentality. Philip Lopate does this well. So does Elena Passarello. E.B. White too, though he’s a bit subtler about it. Not that self-deprecation or humor is merely a matter of deciding to take yourself less seriously. I revise a ton. I read things out loud to myself. I experiment. I once heard Amy Leach say that she rereads her drafts and cuts out everything that doesn’t keep making her laugh. That’s a tall order, but I think it gets at the kind of work required to go from stumbling and fumbling through a memory to artfully crafting something both thoughtful and entertaining.

Right from the title of your collection, you include and represent people close to you in your writing. In “The Lifespan of a Kiss,” you even mention your wife’s “reservations about the writing of this book.” There are a wide cast of characters in these essays—from scouts to your sons. Where is the line between privacy and art? Is there one? What are the implications of our writing authentically about those we love? As nonfiction writers, this is something we’re always negotiating, so how do you navigate this? Do you have a guiding principle on how much you share in your writing? What advice do you have for other writers about sharing stories and details of those close to us?

Philip Lopate says to 1) only have poor friends who can’t sue you, and 2) have lots of friends and a big family so you can afford to lose a few of them. Beyond that, I think there’s a simple metric that anyone can apply to their work to help them answer the question of whether or not they should be writing about a particular relationship. The metric is this—in the act of writing about a particular person, does your empathy for that person increase or decrease? If your empathy for that person increases, you are likely on safe ground. If your empathy decreases, you are likely writing in a way that is more about settling scores and playing the victim than in essaying toward a deeper understanding of yourself and the human condition. And this holds true for writing about people who have done terrible things to us. Empathy is not forgiveness, not exoneration, not whitewashing. Empathy is about understanding and clarity and generosity and finding peace. These are essential virtues of the essay. If I am writing to attack or villainize or complain, then I’m hardly going to find any peace from that. I think James Baldwin’s essay “Notes of a Native Son” is a fine example of this. Baldwin writes with devastating honesty about his father, but in the process of exploring his own experiences with racism, Baldwin comes to empathize with his father and understand the social pressures that shaped his father’s own life. Everyone should read Baldwin. Especially people with daddy issues.

In personal essays, turning yourself into a character is a necessity. Were there any essays where this proved to be more challenging than others? How did you go about choosing how to represent and capture yourself on the page?

I like to think that I’m the same narrator in every essay I write. Virginia Woolf tells us that sincerity is the cardinal virtue of the essayist, and I think that no matter what story I am trying to tell I try to be sincere, to make every comment and reflection and analysis genuine. And that, as with humor, is difficult and, at least for me, requires a lot of revision. If an essay is thinking on the page, then revision is a lot of thinking off the page—thinking about what really should or shouldn’t end up on the page. Sincerity is asking myself over and over again if what I’ve written is really how I feel, or how I felt. Whether the ‘me’ on the page is serious or silly, I try always to be sincere.

Not only do your essays consistently draw a lot of material from your own life and relationships, but they are enriched by so many intersections that reach beyond personal experience. You incorporate a lot of research and imagination. Can you tell us more about your writing process—how do these elements come to be in your essays? How do your essays differ from your initial ideas as they blossom into the essays that are ultimately published?

For me, every essay begins with a personal question, or a memory fraught with emotional significance, some experience I can’t shake, some idea that won’t let me go. From there I brainstorm other events, ideas, people, memories, stories, characters, works of art, etc. that might be related in some way to that question, that memory. I rarely start out with a clear thesis, but as I write about a given memory or idea, a thesis always seems to emerge. In some ways the initial drafting process is a journey from initial inspiration to a clear understanding of some significant human question that is at stake. I don’t think it would work to start with the significant human question. Instead you have to start small. For instance, in my book I write about my father’s year in prison. That whole essay is built off the memory of the stitching on my couch as a kid. It was an old floral-print couch with stitching around the leaves and petals of the flowers. On the night my father told me he was going to jail, I sat on the couch and ran my fingers over that stitching. That tactile memory is one of the most powerful memories of my childhood. So I wrote that scene. Then I did a bunch of research on tactile memory, and the psychology and sociology of touch. And that in turn got me thinking about the notion of ‘touching’ stories and the question of manipulation and the challenge of writing about difficult family stories, and from there the associations sort of came spilling out all over the place and the hard work of the essay was piecing them together in a way that felt natural and pleasing to an audience. What started out as a poignant memory about my father became an essay on loss, forgiveness, and my own insecurities about being a father.

For me, every essay begins with a personal question, or a memory fraught with emotional significance, some experience I can’t shake, some idea that won’t let me go. From there I brainstorm other events, ideas, people, memories, stories, characters, works of art, etc. that might be related in some way to that question, that memory. I rarely start out with a clear thesis, but as I write about a given memory or idea, a thesis always seems to emerge. In some ways the initial drafting process is a journey from initial inspiration to a clear understanding of some significant human question that is at stake. I don’t think it would work to start with the significant human question. Instead you have to start small. For instance, in my book I write about my father’s year in prison. That whole essay is built off the memory of the stitching on my couch as a kid. It was an old floral-print couch with stitching around the leaves and petals of the flowers. On the night my father told me he was going to jail, I sat on the couch and ran my fingers over that stitching. That tactile memory is one of the most powerful memories of my childhood. So I wrote that scene. Then I did a bunch of research on tactile memory, and the psychology and sociology of touch. And that in turn got me thinking about the notion of ‘touching’ stories and the question of manipulation and the challenge of writing about difficult family stories, and from there the associations sort of came spilling out all over the place and the hard work of the essay was piecing them together in a way that felt natural and pleasing to an audience. What started out as a poignant memory about my father became an essay on loss, forgiveness, and my own insecurities about being a father.

No one wants to hear about my family’s sad story, but maybe if I can contextualize my family’s sad story in a way that audiences can see how it relates to their own life, then maybe they’ll be interested in reading. In some ways, the ‘other’ stuff in a personal essay is there to satisfy my own curiosity, but if it satisfies mine, it may also satisfy a reader’s.

These essays span a lot of time and really varying life circumstances, but ultimately they feel like a cohesive collection. As this is your first collection, tell us about the process of bringing pieces together to form a book. Did collecting them offer any surprises that a single essay didn’t offer before?

I’ve often heard that writers should write what they know. The first ten years of my writing life also happen to have coincided with the first ten years of my marriage, and so this book, which includes work I wrote between the ages of 24 and 34, has a decidedly domestic theme. That said, I didn’t set out to write a bunch of essays about marriage and fatherhood. In fact, I was determined to write on a variety of subjects, but I almost always come back, in some way, to family, fatherhood, marriage—relationships in general. I’m a hugger, and I think essays just make me want to give everyone hugs. That’s the thing I learned as I put the essays together—I write about what’s going on right now in my life. (And this fact has meant some added pressure to have a life worth writing about).

Mormonism definitely has a presence in your work, from mentions of your missionary days to church callings and even contextualizing Mormon culture. How do you see your religious background shaping your essays?

I just reviewed Mary Lythgoe Bradford’s Mr. Mustard Plaster and Other Mormon Essays for Dialogue, and that collection of essays has had me thinking about this question a ton. In a nutshell, as a personal essayist, you cannot escape your culture. You can’t pretend it doesn’t exist. Not if you want to be truly authentic. I’ve always been a little concerned about being labeled a “Mormon Writer,” but that’s exactly what I am, whether I make a point of it or not. I love the texture that comes from Brian Doyle’s Catholicism or Dinty W. Moore’s Buddhism. Terry Tempest Williams writes with such intimacy about her Mormon heritage. I am interested in writing about my life, and as my faith has shaped my life experience from the day I was born, to not include it would be disingenuous, and maybe even a little cowardly. That said, because of Mormonism’s reputation for proselyting zeal, I try to write about my faith in a way that allows readers to look in on my life and my culture without feeling preached at.

I just reviewed Mary Lythgoe Bradford’s Mr. Mustard Plaster and Other Mormon Essays for Dialogue, and that collection of essays has had me thinking about this question a ton. In a nutshell, as a personal essayist, you cannot escape your culture. You can’t pretend it doesn’t exist. Not if you want to be truly authentic. I’ve always been a little concerned about being labeled a “Mormon Writer,” but that’s exactly what I am, whether I make a point of it or not. I love the texture that comes from Brian Doyle’s Catholicism or Dinty W. Moore’s Buddhism. Terry Tempest Williams writes with such intimacy about her Mormon heritage. I am interested in writing about my life, and as my faith has shaped my life experience from the day I was born, to not include it would be disingenuous, and maybe even a little cowardly. That said, because of Mormonism’s reputation for proselyting zeal, I try to write about my faith in a way that allows readers to look in on my life and my culture without feeling preached at.

You have a clear zeal for the essay and are invested and involved in current conversations about the form, as evidenced by your strong conference attendance and participation, articles, events, etc. You also teach at BYU, hold Church callings, and, as illustrated in this collection, have a rich family life. So what does this look like in your daily life? How do you balance family, profession, and writing? What sorts of habits have you cultivated to maintain successful writing and family life?

A professor’s schedule gives me time to write. I don’t know how I would do it if I didn’t have it built into my workday. Maybe I’d write on nights and weekends if I was an accountant—I’d probably keep a journal or write some self-important blog about balancing accounts and balancing family life—but more than likely writing would become something I used to do, like swing dancing or mountain biking, just another hobby I don’t have time or energy for anymore. That’s a depressing thought. Then again, maybe I only feel that way because writing is part of my job description, and all things being equal, I have less getting in the way of my desire to write than, say, an accountant. And for that, I am grateful. It’s a privilege to get paid to while away a part of my day on what Montaigne called a “vain and foolish undertaking.” And to show my gratitude, I try to make the most of it. I set yearly writing goals and semester writing goals and daily writing goals. I aim to submit to contests and to hit particular journal submission windows. I try to write or revise a little every day. I have a dorky little wheel chart outside my office called the “Whirling write-o-meter,” and each day I move the center arrow to one of four quadrants: “500 words I don’t hate,” “stared at my screen for an hour,” “revision day,” and “fail.” The goal is 500 words a day. Don’t ask me how often I reach it.

What projects are you currently working on? What can we plan on seeing from you in the future?

My next big project is a memoir about my two grandfathers—one was a complete louse who spent most of his life cheating women out of their money and peace of mind, and the other was a Mormon bishop, Scoutmaster, and union leader who spent most of his life sacrificing of himself for his family. Both were depressed, both felt inadequate as men, and I regularly feel both of them wriggling under my skin. But I’m worried about that project because it doesn’t lend itself to silliness, and I like a little silliness in my writing. Maybe I’ll write some Hallmark cards and bad sermons.

Joey Franklin received his Ph.D. in Literature and Creative Writing from Texas Tech University in 2012. He is an Assistant Professor of English at BYU. Among his awards are a 2006 Grand Prize, Random House Contest, Twentysomething Essays by Twentysomething Writer’s, for his essay “Working at Wendy’s”, and having “Houseguest” named a “Notable Essay” in 2015 Best American Essays.

Joey Franklin received his Ph.D. in Literature and Creative Writing from Texas Tech University in 2012. He is an Assistant Professor of English at BYU. Among his awards are a 2006 Grand Prize, Random House Contest, Twentysomething Essays by Twentysomething Writer’s, for his essay “Working at Wendy’s”, and having “Houseguest” named a “Notable Essay” in 2015 Best American Essays.

His 2015 AML award citation read, “My Wife Wants You to Know I’m Happily Married is like its cover: unassuming, honest, with all the earnestness of a t-shirt wearing T-ball parent trying to make good in this life. But while many of the essays in this debut collection chart the familiar territory of family and marriage, the high artistic rendering of its subjects is anything but familiar. Each of the 14 essays reveals a fascination with language, whether it be in the profane-sounding Japanese word Shukufuku on a new missionary’s tongue or in a toddler’s first acquisition of words. At times lyrical or self-deprecating, Joey Franklin guides us through young family life, through fast-food jobs and crappy cars, through T-ball and male-pattern baldness and teaching a child to pray. My Wife Wants You to Know I’m Happily Married is a beautiful book—sharp and clear, like a jewel under light.”

Elizabeth Tidwell is an essayist who received an MFA in Creative Nonfiction from Brigham Young University in 2015. Her writing has appeared in Santa Clara Review, Brevity, and BYU Studies Quarterly. She currently teaches creative writing, composition, and yoga at BYU.

Thank you Elizabeth and Joey!

Really good questions, really interesting answers. Thanks for sharing. Some random thoughts/questions in response (officially directed at Joey Franklin, I suppose, but I would welcome anyone’s thoughts in response):

– I like your point about the essay being a form that is well-suited for personal reflection. In that, I think (from my limited experience) that it contrasts with fiction, which is personal in a less reflective and more generative sense: less about the journey of the explorer, and more like God in Eden (or a cook in the kitchen). Thoughts?

– Do you continue to have interests in writing fiction as well as essays? If not, do you think you might someday?

– I sometimes think that part of the art of the successful personal essay is bringing together as many disparate things as you can and still feel like there’s a sense of underlying unity or (eventual) focus.

– I like the criterion about whether or not an essay raises personal compassion, but I suspect some people are made uncomfortable by clear-sighted compassion directed toward themselves. Have you had that experience in the people you write about (or don’t write about, perhaps for that reason)?

– Which leads to the question: Are there any essays you’ve felt that you can’t write, or if written, that you can’t publish — because they would be misunderstood, or damage lives, personal relationships, or institutions that are important to you?

– I love the idea of the two-grandfather memoir! Yet another thing to go on my to-read list…

Personal essay by Mormon academic authors seems to be going through a small renaissance. Three authors have had collections of personal essays published by the University of Nebraska Press in the last three years: Eric Freeze, Joey Franklin, and Patrick Madden. Madden also had a book published by Nebraska in 2010, so I guess he started the trend. I think all three of them went from studying at BYU to getting a higher degree at Ohio University, again a trend started by Madden. Is that right, Joey?

Also, the Notable Essays of 2015, from Best American Essays, 2016, were just announced. Among the Mormon authors were:

Matthew James Babcock (BYU-Idaho). “Boogaloo Too.” Small Print Magazine, Spring/Summer.

Joey Franklin (BYU) “The Full Montaigne,” in Ninth Letter, 12:2, Fall-Winter.

Lance Larsen (BYU), “Too Many Mysteries to Shake a Stick At”. The Southwest Review, 100:1.

Patrick Madden (BYU), “Spit”. Fourth Genre, Spring.

Scott Russell Morris (Texas Tech), “Speak English, Please” The Chattahoochee Review 33:1, Spring.

Phillip A. Snyder (BYU), “Rental Horses”. Sport Literate, 9:2.

Babcock, Franklin, Larsen, and Madden are on a roll, they were also on the list of 2014 Notable Essays last year. That year it was:

Matthew James Babcock. “My Nazi Dagger”. In War, Literature, and the Arts.

Joshua Foster. “Bring on the Spins”. Tin House

Joey Franklin. “Houseguest”. Mid-American Review

Lance Larsen. “I Am Thinking of Pablo Casals.” Southern Review

Patrick Madden. “Aborted Essay on Nostalgia.” Tusculum

Looking at the list of those names, its maleness sticks out. Certainly there are Mormon women graduating from academic writing programs, I am surprised that I don’t see any mentioned in “Notable Essays”. Despite so many Mormon women writing personal essays online. For example, Segullah is featuring the work of author Meg Conley this month. http://segullah.org/genre/interviews/interview-with-meg-conley/

‘Certainly there are Mormon women graduating from academic writing programs, but they don’t seem to have reached this elite status of mentions in “Notable Essays”. ‘

At the risk of being criticized for tooting my own horn, I will say: I have had a couple of essays mentioned in the Notable Essays section: “Keeping Abreast of Beauty” from “Bayou” 54 (2010) was listed as a “Notable Essay of 2011″ (yeah, the year on the journal is 2010, but it didn’t appear until 2011) in Best American Essays 2012, while “Leap Year” from “Alaska Quarterly Review” 27.3&4 (2010) was listed as a “Notable Essay of 2010″ in Best American Essays 2011. “Leap Year” is even very much about Mormonism.

I also had an essay–“Satin Worship” from “PMS” 4 (2004)–printed in Best American Essays 2005. In that volume, I’m in the company of David Sedaris and David Foster Wallace. My essay discusses, among other things, the connection between Mormonism and an interest in textiles.

Of course, I interrupted sending my own work out for publication in order to publish two books this year featuring the essays of others: the horribly overpriced “Singing and Dancing to ‘The Book of Mormon’: Critical Essays on the Broadway Musical”, coedited with Marc Edward Shaw, and “Baring Witness: 36 Mormon Women Write Candidly about Love, Sex, and Marriage.” It was recently reviewed (by a woman) on this very website. I hope men who are interested in the personal essay and in doing something about literary gender imbalances will take a look at it.

Thanks Holly, that’s great to see. Congratulations on the new books, they look exciting. I did not know about the Book of Mormon Musical critical essays, that’s good to know.