At Utah Valley University, I’m at the intersection of two unique situations.

(Or maybe they’re not so unique. Both situations can be found at other institutions of higher learning in Utah, though probably not to the degree that we have here in Happy Valley. But almost certainly they’re not found in other states. Anyway, the intersection itself is pretty remarkable, imho.)

First: a relatively high percentage of our students are LDS. Some are TBMs. Others are happily separated from churchgoing but inextricably yoked to the culture, a condition they either writhe against or roll with. And a fair number can (and do) say, “I was raised that way but I don’t do it any more.” They’re proud of it. Mormon, but not. We have a lot of those.

Second, we have a burgeoning creative writing program. There are more students in this emphasis in the English Department than in literary studies, Writing Studies, or education.

Mormon young people of all stripes, and a blossoming creative writing program—what more exciting intersection could there be?

Within that program, I teach (along with Karin Anderson and sometimes Lee Ann Mortensen) both fiction and the writing of creative nonfiction—the personal essay that Eugene England introduced me to and mentored me in thirty years ago at BYU. At the time I met him, in the early 1980s, he was Famous and Popular, and was just starting a brand new Intro to Creative Writing class (English 218) focusing on this new genre, neither strictly expository essay nor freely fictive creation. I was a graduate student with small children, dying to write the stories of my life. Really: I felt they were killing me off, those real-life stories I was living, and I needed to speak (write) them so I didn’t lose what was left.

On the first day of that new class, a great overflowing crowd of BYU students, mostly undergrad, spilled from his classroom on the bottom floor of the JKHB out into the hall. It was standing room only, five deep on all sides. I’m short and small but I pushed my way in, determined not to lose this opportunity to write in a new way, or to learn to write it from The Master. The first issues of Dialogue had come to our northern California home years before, when my dad, a marvelous Thinker-and-Doer, had subscribed wholeheartedly to what was going on at Stanford in the Mormon literary world, and so I’d become familiar with England’s name both as an editor and as a writer in that publication. I liked what I’d read. I can’t remember how I learned about his class that semester at BYU, but when he saw the numbers of students clamoring to take it and said he couldn’t possibly add them all and would therefore require us to “audition” by writing something for him in class that first hour, I leaned against the wall and handwrote a passionate letter (no laptops in those days). I would help him grade the papers if he would let me stay in the class, I told him. I had three babies and was already a struggling grad assistant. I was dependable. I knew I could assist him. Here’s my contact info, I told him, begging him to consider my proposal.

That night he called. He’d secured money and an official TA position for me. I taught with him that semester, to my everlasting joy and benefit, and for several semesters after that.

Now I teach his specialty at UVU, have done so for almost fifteen years (after years at BYU that ended when my fiction was deemed “unsuitable for BYU students”). But though Gene was Writer-in-Residence here in the years before his untimely death in 2001, I’ve rarely taught his work. My excuse is that there’s so much amazing cnf to teach!—just check out BYU prof Patrick Madden’s wonderful website, and you’ll see! They’ll find Gene’s stuff on their own…surely…

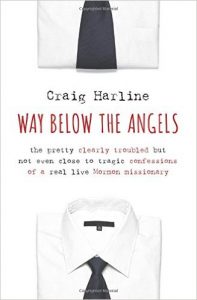

But now — this semester — members of my intermediate creative nonfiction class have spoken up transparently about their LDS experiences (especially missions). I’ve brought them Craig Harline’s nationally-published Way Below the Angels, that delightful “pretty clearly troubled but not even close to tragic” memoir of the life of a “real live Mormon missionary.” I feel justified in saying Look, students, this kind of thing is getting published out there! You can transform your (and your community’s) life by writing your truth! Jackpot! Cha-ching!

But now — this semester — members of my intermediate creative nonfiction class have spoken up transparently about their LDS experiences (especially missions). I’ve brought them Craig Harline’s nationally-published Way Below the Angels, that delightful “pretty clearly troubled but not even close to tragic” memoir of the life of a “real live Mormon missionary.” I feel justified in saying Look, students, this kind of thing is getting published out there! You can transform your (and your community’s) life by writing your truth! Jackpot! Cha-ching!

And so it now also seems imperative to introduce them to essays like “Blessing the Chevrolet” (and Clifton Jolley’s “Selling the Chevrolet” in response), “Healing and Making Peace” (especially in these fraught election months), and my personal favorite, “Easter Weekend” , which I post on Facebook every Easter, hoping some of my “friends” will read it and be as moved as I always am by the grace and beauty of the prose, and the humility of the story. More real life Mormon stuff. More of what belongs by literary and spiritual birthright to my LDS(-and-not) students. Cha-ching!

Gene left a remarkable heritage, to the world of Mormon letters and to multitudes of individual students, friends, and colleagues. Valerie Halladay says in a 1999 Dialogue essay that she learned from him the amazing power of the personal essay to “transform ugliness and chaos into grace and beauty” (86). Later she studied autobiographical theory, she says in the same article, and affirmed for herself that [personal] creative nonfiction is both “discovery [and] creation” (87). Like fiction, creative nonfiction co-creates this plastic, mutable reality we inhabit. Both in the very act of creating, and in tropes, conflicts, motifs, and characters, writers of both fiction and creative nonfiction call on traditions and techniques to make new (sometimes frightening but always, always needed) worlds.

Another time I’ll put forth my theory about the evolution of genres as an expression of the evolution of human consciousness (to use Owen Barfield parlance)—which evolution, my wise friend Duane Hiatt says, has its culmination in Moses 1:39. But what I want to say this time is this: we’re celebrating Dialogue’s fiftieth anniversary this month. One of that magazine’s greatest legacies is the personal essay, the creative nonfiction piece as a legitimate expression of Mormon thought in all its complexity. (See, just as one example, Mary Bradford’s 1978 essay on the Mormon personal essay.)

There are contests. The Sunstone Eugene England Personal Essay contest deadline is in May every year, and Dialogue’s personal essay contest is currently soliciting entries. There will be celebrations on Sept 30, in a Symposium at UVU and in a Gala at the Museum of Natural History in Salt Lake. In Dialogue and its descendants, our heritage, our culture, our very race and people are preserved and enlarged, through narrative, metaphor, exploration and argument both “true” and fictional. It’s a privilege to invite UVU students and other writers to join us in these celebrations. To enter the contests. To always, always keep writing, to create and transform this world. Cha-ching!

I think it is perhaps true that it is in the personal essay that Mormon literary production has come closest to taking its place alongside the best that the (non-Mormon) world has to offer.

.

So . . . have you taught England yet?

Not yet, not at UVU, though I did regularly at BYU (before 1998, when I was deemed “unsuitable”). This semester may be the time.

Just close your eyes and — no, wait…

I need to do this stuff. I love creative nonfiction. Thank you for the links. Will be busy reading.

Would you consider proposing a class to teach in the StoryMakers community sometime? I think that the study of these genres (poetry, short stories, creative nonfiction, Genre bending fiction) and publication opportunities for these, is what AML has to offer the greater LDS writing community.

Yes, I’d be delighted to consider such a class, but I don’t know much about the StoryMakers community, something else I’ve been woefully out of the loop about. Post (or send me) a link?