Let’s talk about stereotypes for a minute. Not the metaphorical stereotypes—characteristics that we assign to different groups of people because we are too lazy to get to know individuals within those groups and prefer to use one-size-fits-all judgments. I want to talk about actual stereotypes—a printing technology that transformed the way that books were made in ways that had profound consequences for the way that ideas were communicated.

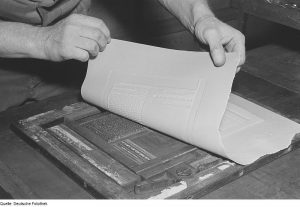

Stereotype printing involved making a plaster mold of a typeset page that could be used to make a metal plate for future printings. Before stereotypes came along, reprinting a book required the enormous time and expense of setting the type all over again. A stereotype was like an early disk drive—it allowed the work of typesetting to be saved so that books could be reprinted quickly and inexpensively.

The stereotyping process was invented in England in 1725, but it was not in wide use in the United States until the 1840s. It was a great convenience to the major publishing houses at that time, but, by the 1860s, it became a major part of the business model of dime-novel publishers like Beadle & Adams, who used stereotypes to reprint and repackage nearly everything they published for multiple generations of readers. And this use of stereotyping led directly to the other kind of stereotyping that we are familiar with.

Let me give a few examples as they relate to Mormon literature.

Let me give a few examples as they relate to Mormon literature.

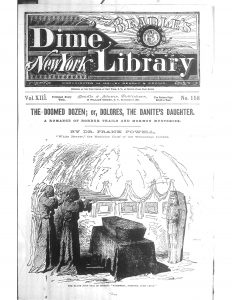

One of the first dime novels involving Mormons was Prentice Ingraham’s Delores the Danite’s Daughter (written in 1881 under the pseudonym “Dr. Frank Powell”), a typical Western adventure of the day involving hooded Mormon Danites who massacre a wagon train and kidnap young women. Buffalo Bill plays a minor role in the drama, as he does in many of the 600 or so dime novels written by Ingraham, who was a paid promoter for the Buffalo Bill Wild West show.

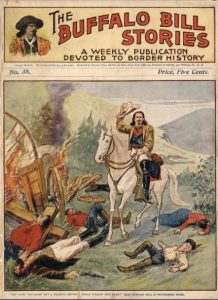

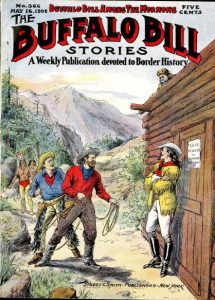

Some 21 years later, in 1902, Buffalo Bill was the king of the dime novel and the subject of his own weekly series called “The Buffalo Bill Stories.” One of the early novels in this series was called “Buffalo Bill and the Danite Kidnappers; or The Green River Massacre”—which, it turns out is simply The Doomed Dozen with the first few pages deleted. When Beadle & Adams went out of business, a new company, Street & Smith, inherited all of the stereotype plates and found a way to repackage them with new covers.

The same series also included such gems as Buffalo Bill Among the Mormons or $5000 Reward, Alive or Dead  (1905; 1915); Buffalo Bill’s Mormon Quarrel or At War with the Danites (1905); Buffalo Bill’s Waif of the Plains or At Odds with the Danites (1908, 1915); and Buffalo Bill at War with the Danites or the Crafty Mormons Darkest Plot (1913). All of these works were repurposed stories by Prentiss Ingraham (who died in 1904). All used stereotype plates left over from the heyday of dime novels. And all extended 19th century stereotypes of the other sort well into the 20th century.

(1905; 1915); Buffalo Bill’s Mormon Quarrel or At War with the Danites (1905); Buffalo Bill’s Waif of the Plains or At Odds with the Danites (1908, 1915); and Buffalo Bill at War with the Danites or the Crafty Mormons Darkest Plot (1913). All of these works were repurposed stories by Prentiss Ingraham (who died in 1904). All used stereotype plates left over from the heyday of dime novels. And all extended 19th century stereotypes of the other sort well into the 20th century.

This same thing happened hundreds of times, not just with Mormons, but with Native Americans, African Americans, Asian Americans, Jews, Catholics, and all of the other categories of human being that made up the stock villain in the dime novels of the 1870s and 1880s. These stereotypes were extended well into the 20th century by publishers who literally had an investment in 40-year-old stereotypes that stigmatized other people. And they continued the stigmatization, not out of hostility, but because they wanted to recoup their sunk costs and produce a product with minimal expense and effort.

This same thing happened hundreds of times, not just with Mormons, but with Native Americans, African Americans, Asian Americans, Jews, Catholics, and all of the other categories of human being that made up the stock villain in the dime novels of the 1870s and 1880s. These stereotypes were extended well into the 20th century by publishers who literally had an investment in 40-year-old stereotypes that stigmatized other people. And they continued the stigmatization, not out of hostility, but because they wanted to recoup their sunk costs and produce a product with minimal expense and effort.

And this is how it often works with the other kinds of stereotypes as well. Stories about Mormon Danites have continued well into the 21st century, not as historical figures, but as LDS security officers wearing suits and ties (and killing dissenters with the same fanaticism of their 19th century analogs). Conceptual stereotypes about Mormons—and lots of other groups and people—often persist in our literature and our lives, not because we are actively hostile, but because we are lazy and do not want to give up our cognitive investment in hurtful and inaccurate ways of thinking and talking about other human beings.

An interesting observation. I find myself wondering: in addition to intellectual laziness and cognitive investments, how does economic investment play into ongoing depictions of Mormons? One very obvious way (in my view) is that there’s at least a perception that scandal, controversy, and oddness sell better in many genres than showing people as ordinary. So in some respects popular depictions of Mormons (or any other group) are always likely to be tilted toward the odd, the foreign, etc.

Has anyone attempted an Edward Said-style reading of literature about Mormons? Does the framework fit?

.

I hadn’t thought of stereotyping, the metaphor, being so literal.