Happy Valentine’s Day! For some time now an idea or theory has been ripening in my mind. It has to do, of course, with children’s literature because as a children’s librarian I spend the greater part of my days surrounded by books and stories and children. One of the great joys of my life is connecting those children with the books I love and I know they will also learn to cherish. I was thinking about the books, new and old, that make an impression on children and add richness to their lives. These are the books that never grow old, the books that continue to be checked out and read and loved year after year after year. They are also the new books that somehow spring to the head of the line and become immediate classics, even if they aren’t about superheroes or demigods or vampires. Sometimes those highly popular books make it onto the “Instant Classics” list, and sometimes they don’t. But what common characteristic do all these books—well-loved and new friends—share? This is where my theory comes in. I think at the very foundation, these books are all about love.

Now I don’t mean romantic love, though sometimes that type of love is hinted at in these books. But the books I’m talking about are primarily children’s books and it seems to me that for a person to have enough depth to be able to form and sustain lasting romantic attachments, there has to be a pattern of forming strong and healthy bonds of love long before romantic love comes into the picture. These books all model and let the reader feel what it is like to experience these strong and healthy types of loving relationships, even if the reader doesn’t have the opportunity to build them in real life (yet). Sometimes I think even simply climbing into a story and learning what these positive and caring relationships feel like can do much to protect children from, or at least lessen the damage that can come when these types of relationships are absent from a child’s real life. But that is a topic for another time. What I want to talk about are a few of the different kinds of loving relationships children can experience through some of the books I consider to be on that Instant Classics list.

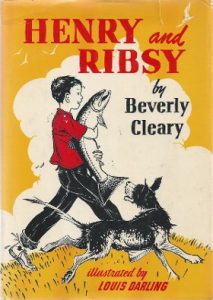

I love the works of Beverly Cleary! Back in 1954 she wrote a book called Henry and Ribsy, and it is all about how young Henry Huggins loves his mischievous dog, Ribsy. In the first chapter, Henry and his father and Ribsy go to the service station to have their car’s oil changed. While Henry’s father walks to the bank and does some other errands, Henry asks if he can please wait at the service station and stay in the car while the car is hoisted up the grease rack as the oil is being changed. Henry’s dad remembers that he always wanted to do that when he was a boy, and the station owner agrees. So Ribsy stays down on the pavement and watches anxiously as the car with Henry in it rises higher and higher into the air. All is going well until a police car stops in front of the supermarket next to the service station. When the policeman opens his car door, Ribsy smells a delicious scent. It is the policeman’s lunch! While the policeman walks into the supermarket to buy a pint of milk to drink with his lunch, Ribsy jumps into the front seat of the police car and begins gobbling. All Henry can do is call to Ribsy and watch in horror as Ribsy gulps down first a sandwich and then a deviled egg. Then out of the supermarket comes the policeman who begins to chase Ribsy!

I love the works of Beverly Cleary! Back in 1954 she wrote a book called Henry and Ribsy, and it is all about how young Henry Huggins loves his mischievous dog, Ribsy. In the first chapter, Henry and his father and Ribsy go to the service station to have their car’s oil changed. While Henry’s father walks to the bank and does some other errands, Henry asks if he can please wait at the service station and stay in the car while the car is hoisted up the grease rack as the oil is being changed. Henry’s dad remembers that he always wanted to do that when he was a boy, and the station owner agrees. So Ribsy stays down on the pavement and watches anxiously as the car with Henry in it rises higher and higher into the air. All is going well until a police car stops in front of the supermarket next to the service station. When the policeman opens his car door, Ribsy smells a delicious scent. It is the policeman’s lunch! While the policeman walks into the supermarket to buy a pint of milk to drink with his lunch, Ribsy jumps into the front seat of the police car and begins gobbling. All Henry can do is call to Ribsy and watch in horror as Ribsy gulps down first a sandwich and then a deviled egg. Then out of the supermarket comes the policeman who begins to chase Ribsy!

As the policeman ran after [Ribsy], Henry was horrified to see him put his hand on the gun on his hip.

“Don’t shoot,” begged Henry. “Please don’t shoot my dog!”

Surprised, the policeman stopped alongside the grease rack and looked all around to see where the voice was coming from.

“I’m up here,” said Henry in a small voice. “Please don’t shoot my dog. I know he shouldn’t have stolen your lunch, but please don’t shoot him.”

The policeman looked startled to see Henry peering out of the car above his head. “I’m not going to shoot your dog,” he said kindly. “I’m just trying to get my lunch back if there’s anything left of it.” . . .

Henry was so relieved to know nothing serious would happen to Ribsy that he was able to grin at the officer. . . .

After Mr. Huggins had insisted on paying for the lunch, the officer drove away and [the service station owner] lowered the car. “You old dog,” said Henry crossly as Ribsy jumped into the front seat. “Look at all the trouble you got me into. . . .” But when Ribsy looked up at Henry and wagged his tail as if he wanted to be forgiven, Henry could not help patting him.

Mr. Huggins looked thoughtful. “It seems to me that dog has been getting into a lot of trouble lately,” he remarked.

“I know he has, but he’s still a pretty good dog,” said Henry.

Yes, children love their pets, and even if a child can’t have a dog for one reason or another, that child can still learn what it feels like to love a dog, even when it misbehaves or eats a policeman’s lunch.

Among my favorite books is a series written by Joan Aiken. These books are about a small girl named Arabel and a very opinionated raven named Mortimer whom Arabel loves dearly. I especially enjoy one section of the first book, Arabel’s Raven, that describes the bond these two share.

Mortimer has just been abducted by a gang of jewel thieves who are holing up in an abandoned subway station. Arabel is distraught.

Arabel was more than upset, she was in despair. She wandered about the house all day, looking at the things that reminded her of Mortimer—the fireplace bricks without any mortar, the tattered hearthrug, the plates with beak-sized chips missing, the chewed upholstery, all the articles that turned up under carpets and [linoleum], and the missing stairs. The carpenter hadn’t come yet to replace them, and Mr. Jones was too dejected to nag him.

“I wouldn’t have thought I’d get fond of a bird so quick,” he said. “I miss his sulky face and his thoughtful ways, and the sound of him crunching about the house. Eat up your tea, Arabel dearie, there’s a good girl. I expect Mortimer will find his way home by and by.”

But Arabel couldn’t eat. Tears ran down her nose and on to her bread and jam until it was all soggy. That reminded her of the flood Mortimer had caused by backing up the bathroom plug, and the tears rolled even faster.

Eventually Arabel figured out where Mortimer was, so she quietly walked to the subway station to bring him home again. There was a huge crowd gathered at the station, and because Arabel was so small she was able to slip between people’s legs and go inside.

When Arabel was inside somebody kindly picked her up and set her on top of the fivepenny ticket machine so she could see. . . .

Just at this moment Arabel (still sitting on the fivepenny ticket machine for she was in no one’s way there) felt a thump on her right shoulder. It was lucky that she had put on her thick warm woolly coat, for two claws took hold of her shoulder with a grip like a bulldog clip, and a loving croak in her ear said,

“Nevermore!”

“Mortimer!” cried Arabel, and she was so pleased that she might have toppled off the ticket machine if Mortimer hadn’t spread out his wings like a tightrope walker’s umbrella and balanced them both.

Mortimer was just as pleased to see Arabel as she was to see him. When he had them both balanced he wrapped his left-hand wing around her and said, “Nevermore” five or six times over, in tones of great satisfaction and enthusiasm.

What a wonderful feeling—to be reunited with the person (or raven) you’ve been longing and pining to see! When children read about Arabel and Mortimer’s joyful reunion, they can feel the vicarious completeness and satisfaction of being again with someone they love very much who has been away and then comes back. Reading about this kind of happy experience is especially helpful, and even cathartic, if the child who is reading is missing and longing for someone who may not be able to come back, or may not return for a very long time. Passages like this keep hope alive, the kind of hope that keeps love strong even across long distances and many years.

Children don’t often understand the love their parents have for them. In fact, maybe that love is something children won’t ever completely understand until they have a child of their own. But in the book Cosmic, by Frank Cottrell Boyce, Liam Digby has an inkling of what it feel like to have the responsibility of being a father, even if he doesn’t quite understand the love part. Liam and Florida have been pretending to be father and daughter for quite awhile. Liam is very tall for his age, and he has scruffy facial hair. Florida is a normal 12-year-old, and when they discover that they can do a lot of things 12-year-olds can’t usually do (like almost test-drive a Porsche) if Liam pretends to be Florida’s dad, well, they get a bit carried away. In this book Liam and Florida win a trip for father and daughter to go to a secret place in China where the greatest thrill ride of all time is being built. It is an actual rocket that will send four lucky children into space!

So Liam spends a lot of time learning to do “dadly” things like golf and driving a car and using child psychology. He also finds out that the children will be going into space alone, and his newly acquired fatherly skills kick in. He talks to the other, real dads:

“You think you’re a good dad?” [Liam asks], “What kind of parent lets his child go off into space while he plays golf?”

Monsieur Martinet looked a bit confused when I said that. And so did the other dads. Until Dr. Drax said, “Aren’t you doing exactly that, Mr. Digby?”

Well, yes I was, but I knew that my dad would never do that. Let alone my mum. I said, “In my school — my child’s school — when they go on a trip, a responsible parent goes with them. Even if it’s only to the museum or the art gallery. In the New Strand Shopping Centre, you’re not even allowed to go into the newsagent without an accompanying adult. Why aren’t you doing that here?”

“You mean you’d like to go to space with the children?” asked Dr. Drax.

“Yes. Yes, of course I would!”

Eventually Liam is chosen as the “responsible adult” to accompany the children. But just as they are about to get into the rocket, Liam realizes what a huge and dangerous thing they are going to do. He openly and honestly tells Dr. Drax that he is not an adult, just a very large, hairy boy. But she doesn’t understand. So he talks to Florida:

“We’re in terrible danger. We’ve got to get out of here. You thought it was bad when I nearly drove a Porsche. A Porsche goes 170 miles an hour. Do you have any idea how fast the [rocket] goes? We’re in trouble.”

“You’re my dad, get me out of it.”

“No. That’s just it. I’m not your dad. . . . Ring your real dad.”

“What for?”

“We’re in trouble. He can get us out of it. He’s a dad. That’s what he’s for.” I was thinking about how simple it all was. Florida would ring her dad. He’d probably go nuts. But, from then on, I would no longer be in charge. I wouldn’t have to be a grownup anymore.

But Florida couldn’t call her dad, so Liam figures he needs to see this thing through to the end. So he goes on the rocket with the children. At one point, when Liam sends the children off to have a bit of fun on the moon while he keeps things running smoothly on the rocket, his actual father calls and they have a good and loving conversation. Liam said later:

It might look like a coincidence that Dad rang me up just as the phones came on. But it wasn’t. He’d been trying for days and days. He got through the moment they came back on because he’d been trying all the time—that’s what dads do. I had to look out for the children, like Dad looked out for me and his dad had for him, right back through time. Dadliness was out there among the stars, a force like gravity, and I was part of it.

I think that “Dadliness” as Liam calls it, is another word for love. And this Dadliness endures forever, even if a family situation changes, even if a father isn’t able to live full-time with his children. The love continues and grows. This book helps children realize some truths about a father’s love as they see Liam begin to understand some things about this love himself.

There are so many, many different types of love a child is exposed to in literature. I like the poignant story of San Fairy Ann in Eleanor Farjeon’s book The Little Bookroom. In this story, set in England during the Second World War, young Cathy Goodman has been evacuated to the countryside to escape the bombing in London. For four years she has lived in a little country village, and for four years she has been scowly and miserable and sad. Why? Because the very first day she had arrived in the village, a boy had snatched Cathy’s beautiful and treasured doll from her arms and had flung it into the duckpond. As a result, Cathy Goodman had never fitted in, and never tried to. But nobody had ever known the reason.

But the beautiful lost doll had her own special history, and she couldn’t stay lost forever. When the citizens of the village decided to clean out the duckpond, many things were found.

In the middle of the pond stood Mrs. Lane, her sleeves rolled up, her cotton shirt tucked into her shorts, her legs encased in the doctor’s rubber boots, her capable hands raking the slime as she passed her findings to Miss Barnes, on the hard caked mud. The children framing the banks made rubbish piles, to be carted away tomorrow.

. . . On the edge of the crowd, staring with all her heart in her eyes, stood Cathy Goodman. If Bobby Maitland’s wooden horse was found, why not San Fairy Ann?

The hunt went on. Nine o’clock chimed. Mothers began to chase their children to bed. Mrs. Vining (the mean lady Cathy lived with) screamed to Cathy to come in. Cathy slipped behind a bush and hid. When ten o’clock chimed there was almost no one left but Mrs. Lane and Miss Barnes. The green showed three big dumps, and not a tin was visible in the pond. San Fairy Ann had not come to light. . . . San Fairy Ann still lay under the mud in the middle of the pond. No wonder Mrs. Lane hadn’t raked her up. She had been standing right on top of her all the time.

Twelve o’clock chimed . . . Mrs. Lane slipped out of bed to smell the jasmine at her window and look at the moon on the green. . . . She caught her breath. What was that muffled sobbing sound in the night? And what was that in the middle of the pond? Had a dog or a sheep floundered in? Oh mon dieu! It’s a child!

Mrs. Lane was down the stairs and out of the house in a flash. In the hall she snatched up the muddy wellingtons as she ran, and thrust her pajamaed legs into them, scarcely stopping. Within two minutes of seeing her from the window, Mrs. Lane was lifting Cathy Goodman out of the slime. They stood clutching each other in the middle of the pond. Cathy was a dreadful sight, soaked with mud, her wet hair streaked with duckweed.

“San Fairy Ann! San Fairy Ann!” she sobbed.

“Cathy, cherie, what is it?”

“San Fairy Ann!”

“Tell me, pauvre petite.”

“I want San Fairy Ann.”

“Who is she, San Fairy Ann?”

“You never fished her out. You fished out Bobby’s horse, but you left San Fairy Ann.”

“She’s your doll!” cried Mrs. Lane, light breaking on her. “Stop crying, cherie—we’ll find her if we have to fish all night.”

Cathy stopped sobbing and stared. Were people kind, after all, then? Regardless of her pajamas, Mrs. Lane knelt in the mud and groped with both her hands. What was this? Only another tin. She must be careful. Ah! Here was something smooth and hard. A stone? She brought it into the moonlight. Not a stone, a china head, with glossy black hair, blue eyes, and a rosy mouth.

Cathy Goodman turned red with happiness. “San Fairy Ann!” she screamed.

After she was clean and warm and still clutching San Fairy Ann, Cathy listened to Mrs. Lane.

“Tomorrow,” said Mrs. Lane, we will cut . . . a new dress for San Fairy Ann, with a lace petticoat underneath.”

Cathy stared at her, unable to speak. Suddenly the scowl came unpuckered from her face, her face was so nice when it smiled that, just as suddenly, [Mrs.] Lane’s eyes filled with tears. She put her arms around the little girl and the doll, saying “And Cathy,—would you and San Fairy Ann like to stay here and live with me?”

“Oh!” gasped Cathy Goodman.

Sometimes children need to know that they are loved, even when they seem, or even feel, unloveable. Reading about grumpy Cathy Goodman finding not only the treasure of her heart but a loving home as well can rekindle in a child’s heart that fluttering hope that never quite dies, the hope that despite all the bad and hard and sad things in life, there really can be joy again, and a true home, and love.

Finally I have to mention the love of a true friend, a friend who stays faithful and loving through all things, good and bad. Because friendship is such an important foundational part of a child’s life, I think that through reading about the example of a true and loving friend, children can recognize true friendship when they find it, and in turn become true friends to others. This can eventually help them to cultivate these types of lasting friendships in their homes and families and lives. One of the best examples of true friendship in any book is the friendship of Charlotte and Wilbur in E. B. White’s Charlotte’s Web.

Wilbur felt lonely and friendless.

“One day just like another,” he groaned. “I’m very young, I have no real friend here in the barn, it’s going to rain all morning and all afternoon, and Fern won’t come in such bad weather. Oh, honestly!” . . .

Wilbur didn’t want food, he wanted love. He wanted a friend, someone who would play with him. . . . This was certainly the worst day of his life. He didn’t know whether he could endure the awful loneliness anymore.

All people, children and adults alike, can have moments like this of existential angst, times when one feels completely alone and sad. At times like this, even the strongest person can wonder about the purpose of life and whether it is all worthwhile or not. At such times, a true friend can make all the difference.

Darkness settled over everything. Soon there were only shadows and the noises of the sheep chewing their cuds, and occasionally the rattle of a cow-chain up overhead. You can imagine Wilbur’s surprise when, out of the darkness, came a small voice he had never heard before. It sounded rather thin, but pleasant. “Do you want a friend, Wilbur?” it said. “I’ll be a friend to you. I’ve watched you all day and I like you.”

“But I can’t see you.” said Wilbur, jumping to his feet. “Where are you? And who are you?”

“I’m right up here,” said the voice. “Go to sleep. You’ll see me in the morning.”

And we all know what happened next. Wilbur woke up and met Charlotte A. Cavatica, a large grey spider. She proved to be a true friend to Wilbur. She made it her life’s work to save him from the butcher’s block by writing miraculous words in her web and by giving Wilbur love and encouragement as long as she lived. She succeeded and saved Wilbur’s life.

Mr. Zuckerman took fine care of Wilbur all the rest of his days, and the pig was often visited by friends and admirers, for nobody ever forgot the year of his triumph and the miracle of the web.

The book ends with one of my favorite paragraphs in all of literature:

Wilbur never forgot Charlotte. Although he loved her children and grandchildren dearly, none of the new spiders ever quite took her place in his heart. She was in a class by herself. It is not often when someone comes along who is a true friend and a good writer. Charlotte was both.

So many kinds of love! And I have mentioned only a few: the love of pets, love requited after absence, familial love, the need for love even when someone isn’t very loveable, and the love of a true friend. When children read about these different kinds of love. They start to recognize and build the foundations that can support different manifestations of love in their own lives. Reading can do this, and love can do this. I firmly believe in the power of carefully crafted words and thoughts to make a positive difference in the lives of people of all ages. By starting young and reading and internalizing stories about love and hope and home and family, children can develop patterns and habits of love and compassion that will stay with them, not just in childhood, but as long as they live. Reading keeps that hope—the hope of love and joy and eventual resolution of all things—alive and fluttering always in the heart.

Works Cited:

Aiken, Joan. Arabel’s Raven. Garden City, New York, Doubleday and Company, Inc. 1974.

Cleary, Beverly. Henry and Ribsy. New York, William Morrow & Company. 1954.

Cottrell Boyce, Frank. Cosmic. London, Macmillan Children’s Books. 2008.

Farjeon, Eleanor, “San Fairy Ann,” The Little Bookroom. New York, The New York Review Children’s Collection. 1955.

White, E. B. Charlotte’s Web. New York, Harper Collins Publishers. 1952.

Great post. Everything you wrote here resonates for me. (Including the references to Mortimer and Arabel — a far-too-neglected classic.)

Many years ago, sf&f author Marion Zimmer Bradley wrote what I think may be the single best essay I have ever read about The Lord of the Rings, titled “Men, Halflings, and Hero Worship,” in which she argues that LOTR is fundamentally about love, with the love of Frodo and Sam as the centerpiece.

Part of the value of fiction, I think, lies in its capability to provide us with vicarious emotional experiences. We see love, and come to experience love for the characters we read about — and that love is real, even if the characters are inventions, strictly speaking.

I’m the sort of person who doesn’t cry when bearing a testimony. It’s just not in me. But I will cry when I get to the point in The High King when Fflewddur Fflam breaks his beloved harp for firewood when his friends are freezing to death, with the words, “Burn it. It is wood well-seasoned.” (And is repaid by an astonishing fire that lasts all night long, with ever song the harp had ever played sounding again as it burns. Love returned, indeed.)

It can even happen in video games. Just a couple of weeks ago, the rest of my family watched my oldest son complete a game titled “The Last Guardian.” I’m not much a one for video games — especially ones that involve a lot of jumping and manual dexterity. But this one was a very unusual video game indeed, in which yourself as the point of view character comes to bond with a large animal companion, each of you rescuing the other many times over, until… well, I won’t give it away. Suffice it to say that at the end of the game, every one of us watching had tears streaming down our faces.

Thanks for writing.

This reminds me that Beverly Cleary turned 100 last year. Here’s a story about it.

http://www.npr.org/2016/04/11/473558659/beverly-cleary-is-turning-100-but-she-has-always-thought-like-a-kid

I thought it was recent but it’s been almost a year.

A lovely piece by someone who is herself ‘a true friend and a good writer’ and who has found, as a children’s librarian, an ideal role in which to share these skills. I live in England where due to lack of public funding libraries have been under threat of closure, but this has led to much public support and discussion of the importance of libraries ( and stories!) for children. A librarian plays such an important role with her knowledge of books and writers, and the ability to pass on those which will speak to a particular child.

I’m delighted to see that Eleanor Farjeon’s ‘Little Bookroom’ is still available, I read it as a child, but those wise stories have stayed with me ever since. Frank Cottrell Boyce is a splendid writer, and has been one of the most vocal defenders of the Library support movement. I have to confess that Joan Aiken is my mother, and I love her books too, many of her stories were told to me as a child! By great good fortune, it was through a mutual enjoyment of her writing that I came to know Kathryn some years ago – evidence of the truth that books can teach us about and encourage friendship!

Thank you, Kathryn, for “It’s All About Love.” I completely enjoyed each word of this spot on essay. Hooray for great books, and reading and libraries! They give us ideas and concepts and strength we can draw on for the rest of our lives.

And how delightful to have the response from Lizza Aiken. And I’m reminded of how much I loved reading Joan’s book to my family.

Lizza, here’s an idea for a campaign to save all the English libraries:

Consider how many great writers (and almost great, and even not-so-great writers) tell tales of their fondness for and devotion to libraries and librarians, many of them marking the library moments of their lives as the turning point that set them on the path to literary expression. Think of the legacy of Great English Writers that would fade from existence if we lose our libraries! It would be a catastrophe of Alexandrian proportions!

I don’t know, maybe that’s a bit over wrought, but it might be worth a try.