In 1732 Jonathan Swift published “The Lady’s Dressing Room,[i]” a poem commenting on contemporary vanity. At 144 lines, it might not seem too long to enter into this post, and I might be willing to enter it in its entirety, but Swift, as anyone who has read Travels into several remote nations of the world, in four parts / by Lemuel Gulliver, first a surgeon, and then a captain of several ships, will know, Swift was, not to put too fine a point on the matter, a satirist. That work was first issued in a bowdlerized edition in 1726, and then in an amended edition in 1735[ii], after “The Lady’s Dressing Room” was published.

In 1732 Jonathan Swift published “The Lady’s Dressing Room,[i]” a poem commenting on contemporary vanity. At 144 lines, it might not seem too long to enter into this post, and I might be willing to enter it in its entirety, but Swift, as anyone who has read Travels into several remote nations of the world, in four parts / by Lemuel Gulliver, first a surgeon, and then a captain of several ships, will know, Swift was, not to put too fine a point on the matter, a satirist. That work was first issued in a bowdlerized edition in 1726, and then in an amended edition in 1735[ii], after “The Lady’s Dressing Room” was published.

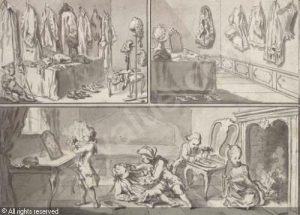

But Swift was a satirist, not a satyrist, although a lady named Satira appears in the poem. It has been controversial from the first, being considered sexist. But at least one of the problems with that view is that the satire is more anti-humanist, which allows Swift to vent in 144 lines on every human vice, folly and defect. He was, after all, a clergyman, Dean of St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin. But before that, he was born, in Dublin, to Anglo-Irish parents who had come to Dublin to seek their fortune. His father died seven months before he was born,[iii] and his mother left him in Dublin and returned to England. I’m sure that had nothing to do with “The Lady’s Dressing Room,” in which a swain, one Strephon, steals into his lady Celia’s dressing room and finds all in disarray and gross display. After 114 highly descriptive lines laying all that out, Strephon finds himself in a bind. As Swift has it:

Thus finishing his grand Survey, [115]

Disgusted Strephon stole away

Repeating in his amorous Fits,

Oh! Celia, Celia, Celia shits!

The remaining 26 lines propose a remedy to Strephon’s ill, as you can read here,[iv] but it is with Strephon’s reaction that I am concerned, because it seems to me to explain Pound’s reaction to the modern world. Pound seems as ambivalent about European culture as about American, especially in the early 20th century. He spends a great deal of effort and energy to master and to subvert both. The Library of America provides a good summary of his career:

…Pound was in the swirling center of poetic change. In such early volumes as Ripostes, Cathay, Lustra, and Hugh Selwyn Mauberly — as surely as in his later magisterial versions of the Confucian Odes and the Sophoclean dramas Women of Trachis and Elektra — Pound followed his own directive to “make it new,” opening fresh formal pathways while exploring the most ancient traditions. Before, during, and after the controversies and catastrophes of his public career (culminating in his long residence in a Washington [D.C.] mental hospital while under indictment for treason), Pound remained capable of rare technical brilliance and indelible lyricism.[v]

The Cantos, a long sequence of poems, captures brilliantly both the “technical brilliance and indelible lyricism” of his poetry and the insanity of his economic and anti-semitic ideas, which he thought only he could save the world from, by the brilliance of his thought and the incisive record of it. One of the most coherent of the Cantos is number XLV, published in 1937 by Faber in London and Farrar in New York in The fifth decad of cantos, “Pound’s documentation of the history of usury”.[vi]

W. B. Yeats, in his introduction to the Oxford Book of Modern Verse (written in 1936), captured Pound thus:

When I consider his work as a whole, I find more style than form; at moments more style, more deliberate nobility and the means to convey it than in any contemporary poet known to me but it is constantly interrupted, broken, twisted into nothing by its direct opposite, nervous obsession, nightmare, stammering confusion; he is an economist, poet, politician, raging at malignants with inexplicable characters and motives, grotesque figures out of a child’s book of beasts. This loss of self-control, common among uneducated revolutionists, is rare — Shelley had it in some degree — among men of Ezra Pound’s culture and erudition.[vii]

Pound’s “history of usury” betrays that loss of self-control. It is strongly anti-semitic as well, although in Canto XLV that element is less prominent. But the poem also encompasses Pound’s reaction to European civilization, and it seems to me to marry his knowledge of European civilization and culture with his distress and disgust at what Europe’s wars had done to his generation. In this regard, it seems to me that Pound’s reaction is like that of Strephon, as Swift wrote him. David Myers says that the term “anti-semitic” was invented in Germany in the previous century by a journalist who considered it an honorific.[viii] Pound felt that way, too.

So here is Canto XLV. It has a title, as well

With Usura

With usura hath no man a house of good stone

each block cut smooth and well fitting

that design might cover their face,

with usura

hath no man a painted paradise on his church wall

harpes et luthes[ix]

or where virgin receiveth message

and halo projects from incision,

with usura

seeth no man Gonzaga his heirs and his concubines

no picture is made to endure nor to live with

but it is made to sell and sell quickly

with usura, sin against nature,

is thy bread ever more of stale rags

is thy bread dry as paper,

with no mountain wheat, no strong flour

with usura the line grows thick

with usura is no clear demarcation

and no man can find site for his dwelling.

Stonecutter is kept from his stone[x]

weaver is kept from his loom

WITH USURA

wool comes not to market

sheep bringeth no gain with usura

Usura is a murrain, usura

blunteth the needle in the maid’s hand

and stoppeth the spinner’s cunning. Pietro Lombardo

came not by usura

Duccio came not by usura

nor Pier della Francesca; Zuan Bellin’ not by usura

nor was ‘La Calunnia’ painted.

Came not by usura Angelico; came not Ambrogio Praedis,

Came no church of cut stone signed: Adamo me fecit.

Not by usura St. Trophime

Not by usura Saint Hilaire,

Usura rusteth the chisel

It rusteth the craft and the craftsman

It gnaweth the thread in the loom

None learneth to weave gold in her pattern;

Azure hath a canker by usura; cramoisi is unbroidered

Emerald findeth no Memling

Usura slayeth the child in the womb

It stayeth the young man’s courting

It hath brought palsey to bed, lyeth

between the young bride and her bridegroom

*****************CONTRA NATURAM

They have brought whores for Eleusis

Corpses are set to banquet

at behest of usura.[xi]

As published online, the poem ends with this note, which is not in my 1956 edition of The Cantos (1-95): N.B. Usury: A charge for the use of purchasing power, levied without regard to production; often without regard to the possibilities of production. (Hence the failure of the Medici bank.) As Tytell testifies, this note is Pound’s; I don’t know who edited it out of my edition, possibly Pound, possibly James Laughlin, Pound’s publisher (at New Directions[xii]) after his imprisonment. But Tytell reports a stronger definition by Pound in one of his writings on money: “USURY is the cancer of the world, which only the surgeon’s knife of Fascism can cut out of the life of nations.”

I wonder if this disgust over money is a possible effect of Pound’s father working in the Philadelphia Mint — or maybe that was merely a contributing factor. But this madness stole upon Pound slowly. He published two poems that illustrate the other half of his skill, as set forth by Yeats. These were both published in Poetry in October, 1912. Note that in the first one, Pound is still seeking for greatness in American art. Note also that he compares himself with Whistler:

To Whistler, American

On the loan exhibit of his paintings at the Tate Gallery.

You also, our first great,

Had tried all ways;

Tested and pried and worked in many fashions,

And this much gives me heart to play the game.

Here is a part that’s slight, and part gone wrong,

And much of little moment, and some few

Perfect as Dürer!

“In the Studio” and these two portraits,* if I had my choice![xiii]

And then these sketches in the mood of Greece?

You had your searches, your uncertainties,

And this is good to know—for us, I mean,

Who bear the brunt of our America

And try to wrench her impulse into art.

You were not always sure, not always set

To hiding night or tuning “symphonies”;

Had not one style from birth, but tried and pried

And stretched and tampered with the media.

You and Abe Lincoln from that mass of dolts

Show us there’s chance at least of winning through.

* “Brown and Gold—de Race.”

“Grenat et Or—Le Petit Cardinal.”

Note also that from the line “And then these sketches in the mood of Greece” the poem is written in perfect, and effective, iambic pentameter. This is the young Pound, who, said Yeats, had “more style, more deliberate nobility and the means to convey it than in any contemporary poet known to me.” High praise indeed. But the imagist strain blended with both the iambic line and personal reflection in

Middle-Aged: A Study in an Emotion[xiv]

A STUDY IN AN EMOTION

“’Tis but a vague, invarious delight.

As gold that rains about some buried king.

As the fine flakes,

When tourists frolicking

Stamp on his roof or in the glazing light

Try photographs, wolf down their ale and cakes

And start to inspect some further pyramid;

As the fine dust, in the hid cell beneath

Their transitory step and merriment,

Drifts through the air, and the sarcophagus

Gains yet another crust

Of useless riches for the occupant,

So I, the fires that lit once dreams

Now over and spent,

Lie dead within four walls

And so now love

Rains down and so enriches some stiff case,

And strews a mind with precious metaphors,

And so the space

Of my still consciousness

Is full of gilded snow,

The which, no cat has eyes enough

To see the brightness of.”

“Gilded snow” is an exquisite image; many poets would give much labor to achieve it. He was 27 when he wrote that “study in emotion.” Perhaps he perceived himself as aging more rapidly in his struggles with civilization than other kings had. Or perhaps this is merely “a study in emotion” and nothing more. Or perhaps he felt the emotional and mental instability that was even then setting in. Perhaps he shared Johnson’s disgust about human vanity, which Johnson expressed so memorably in “The vanity of human wishes.”

But few there are whom Hours like these await,

Who set unclouded in the Gulphs of fate.

From Lydia’s monarch should the Search descend,

By Solon caution’d to regard his End,

In Life’s last Scene what Prodigies surprise,

Fears of the Brave, and Follies of the Wise?

From Marlb’rough’s Eyes the Streams of Dotage flow,

And Swift expires a Driv’ler and a Show.[xv]

That was Swift’s fate, as a satirist. As a disappointed world-changer, it was to be Pound’s, had not Robert Frost taken up his case. Hard to know. He continued to write and publish, and when he was released from St. Elizabeth’s, he went back to Italy. But hold on, I hear you say: Robert Frost?

Your turn

____________________

[i] Says Wikipedia, in its article https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Lady’s_Dressing_Room, accessed 21 July 2017.

[ii] Thanks, Wikipedia, for the article https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gulliver’s_Travels, accessed 26 July 2017.

[iii] Thanks again, Wikipedia, for another article, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jonathan_Swift, accessed 26 July 2017.

[iv] http://andromeda.rutgers.edu/~jlynch/Texts/dressing.html, accessed 23 July 2017

[v] Leaflet included in Poems and translations / Ezra Pound ([New York] : Library of America, c2003).

[vi] Ezra Pound : the solitary volcano / John Tytell (New York : Doubleday, 1987), p. 247.

[vii] Ibid., p. 246.

[viii] Jewish history : a very short introduction / David N. Myers (New York : Oxford University Press, 2017), p. 19.

[ix] Corrected from “luz” in consultation with The cantos (1-95) / Ezra Pound (New York : New Directions, c1956), fifth decad, p. 23.

[x] Corrected from “tone,” ibid.

[xi] Ibid., pp. 23-24

[xii] I have trouble not thinking of that publisher as Nude Erections, and I wonder if I am alone?

[xiii] “I,” as published on the Poetry magazine’s website; corrected from Poems and translations / Ezra Pound ([New York] : Library of America, c2003), p. 608.

[xiv] Subtitle (and epigram) not in Poems and translations p. 609.

[xv] The Vanity of Human Wishes : The Tenth Satire of Juvenal / imitated by Samuel Johnson (London : Dodsley, 1749.) Swift expired in 1745.