Michael Austin is a board member of BCC Press.

Michael Austin is a board member of BCC Press.

Shakespeare is great and all, but, on the list of best playwrights in the history of ever, I only consider him #3. In second place is the Greek master Euripides, author of some 92 plays, only 19 of which have survived. Two of them—Medea, the story of a woman who murders her own children in revenge for her husband’s decision to abandon her; and The Trojan Women, a conversation among the noble women of Troy who have been condemned to death or concubinage at the end of the Trojan War—flay me to the core every time I watch or read them.

And in first place is the Norwegian genius Henrik Ibsen, who has been responsible for some of the most uncomfortable evenings of my life. A stage version of Ghosts that I saw in Salt Lake City was two hours of sheer physical discomfort causedby the plot. The Glenda Jackson film version of Hedda Gabler that I used to show students in my World Literature courses was like sitting on the edge of a cliff from start to finish.

And Ibsen took great care to upset everyone more or less equally. He became the darling of European liberalism in 1882, when The Enemy of the People denounced intransigent nationalism and the uncritical acceptance of entrenched beliefs. This lasted for two years, until The Wild Duck gored the liberal sacred cows of social reform and the unflinching pursuit of truth. Ibsen was an equal opportunity annoyer.

As I have tried to understand why the plays that I consider the best are the ones that make me the most uncomfortable, I have pretty much concluded that this is the job of the theatre. Yeah, I know that that’s not where the money is. Dancing cats are going to pack in the crowds every time. But the real artists—Euripides, Ibsen, Strindberg, O’Neil, Wilson, Mamet—are the ones who can sustain a near-impossible level of extreme tension for a whole play and never let us off the hook with an easy resolution.

Why? Because tension is transformative. We don’t like being uncomfortable (which is why it’s called “uncomfortable”). We try to resolve tension. Anxiety and discomfort are basically the only reason that human beings do stuff. Happy and contented people have no reason to change anything—not themselves, and not the world. The immediacy and intimacy of the theatre can provoke a discomfort that no other form of literature can match. We can’t take a break. We can’t put down the book. We just have to keep watching.

So, when we look for Mormon “Miltons and Shakespeares of our own”—and, I might add, Ibsens and Euripides of our own—we need to look for writers who make us uncomfortable and unhappy. We would much rather, of course, find writers who confirm our world view, make us happy, and tell us that everything is going to be OK because we are such superstars. If that’s what you want, you can have it. Here it is. Have fun.

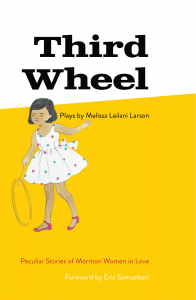

If you would rather be unhappy for a while—and interact with drama that will make you uncomfortable, force you to examine things you would rather keep hidden, and perhaps become a better person as a result, I would strongly recommend the work of Melissa Leilani Larson, one of the true rising stars of Mormon literature, whose book of plays, Third Wheel, was one of four major works by Mormon women published last month by BCC Press.

The two plays in this volume both treat issues head on that most of us would rather not think much about at all. “Little Happy Secrets” deals with same-sex attraction among roommates at BYU. It’s viewpoint character, Claire, is a bright, faithful, returned missionary who loves the gospel, and, also, her best friend and roommate, Brennan. Larson faces all of these realities without flinching.

The two plays in this volume both treat issues head on that most of us would rather not think much about at all. “Little Happy Secrets” deals with same-sex attraction among roommates at BYU. It’s viewpoint character, Claire, is a bright, faithful, returned missionary who loves the gospel, and, also, her best friend and roommate, Brennan. Larson faces all of these realities without flinching.

No reader or viewer of “Happy Little Secrets” will find easy purchase to write Claire off as an apostate or to paint the other characters in the play with the broad brush of homophobia. Either move would allow us to leave the theatre unchanged. Rather, we must deal with the reality of a character who is both fully gay and fully Mormon—a combination of characteristics that cannot exist in the worldviews that many of us cling to. The purpose of a play like this is to challenge those worldviews.

In many ways, the second play, “Pilot Program,” is even more challenging to Latter-day Saint readers. The supposition of the play is that a faithful, infertile couple has been called to be part of a pilot program bringing back the practice of polygamy. There are no huge dramatic plot elements in this play: no explosions, no suicides, nobody is strangled or stabbed. Just three people struggling with difficult emotions and an audience forced to realize that, even after more than a hundred years of strict monogamy, Mormonism has never really resolved the theological implications of the plural marriage we once practiced in this life and continue to practice in anticipation of the next one.

In many ways, the second play, “Pilot Program,” is even more challenging to Latter-day Saint readers. The supposition of the play is that a faithful, infertile couple has been called to be part of a pilot program bringing back the practice of polygamy. There are no huge dramatic plot elements in this play: no explosions, no suicides, nobody is strangled or stabbed. Just three people struggling with difficult emotions and an audience forced to realize that, even after more than a hundred years of strict monogamy, Mormonism has never really resolved the theological implications of the plural marriage we once practiced in this life and continue to practice in anticipation of the next one.

I can think of a lot of things I would rather do than watch one of these plays and be forced to stare the core beliefs of my culture in the face for two hours without blinking. But I can’t think of anywhere that I more NEED to be. The unexamined life is much more fun, but it is also sterile and stagnant. Great dramatists require more of their audiences, and, along with Euripides and Ibsen (and even that Shakespeare fellow), Melissa Leilana Larson is a Great dramatist

I thought the way the violence happened off-screen in Freetown was fairly Greek, though I suppose it was as much the director’s choice as the screenwriter’s. It’s about a group of native Liberian missionaries fleeing violence, trying to make it to freedom in Sierra Leone, and then they have to stop and face what they’re fleeing. There’s also an omen in the ending when you recall that the war flowed over into Sierra Leone not long after the story takes place.

I heard an audiorecording of Little Happy Secrets several years ago. I thought it was on Ewetoob, but maybe the ewes grazed it away. Even the Duckduck couldn’t go find it. Wrenching play.