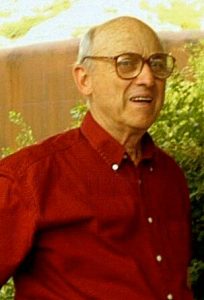

We note with great sorrow the passing of author and educator Douglas H. Thayer. Born April 19, 1929 in Salt Lake City, he passed away on Oct. 17, 2017 after a battle with liver cancer. Thayer grew up in Provo, where he spent his boyhood largely running free and hunting, fishing, and hiking in the surrounding Wasatch Mountains. He swam naked in the Provo River and polluted Utah Lake. He later said that swimming in the poisoned lake gave a quick, cheap immunization against every known disease, if you survived.

We note with great sorrow the passing of author and educator Douglas H. Thayer. Born April 19, 1929 in Salt Lake City, he passed away on Oct. 17, 2017 after a battle with liver cancer. Thayer grew up in Provo, where he spent his boyhood largely running free and hunting, fishing, and hiking in the surrounding Wasatch Mountains. He swam naked in the Provo River and polluted Utah Lake. He later said that swimming in the poisoned lake gave a quick, cheap immunization against every known disease, if you survived.

Thayer dropped out of high school in 1946 to join the U.S. Army, serving in Germany. He came home, attended Brigham Young University for a year, and then returned to Germany for 30 months as a missionary for the Church. While on his mission he was called up to fight in Korea, but was allowed to continue his mission. He later said that while he had no desire to kill or be killed, he felt he missed his war, a great deprivation for a writer who liked Hemingway.

Thayer dropped out of high school in 1946 to join the U.S. Army, serving in Germany. He came home, attended Brigham Young University for a year, and then returned to Germany for 30 months as a missionary for the Church. While on his mission he was called up to fight in Korea, but was allowed to continue his mission. He later said that while he had no desire to kill or be killed, he felt he missed his war, a great deprivation for a writer who liked Hemingway.

After his mission Thayer returned to BYU, and graduated with a bachelor’s degree in English. He applied to law school, but then decided not to attend and started a doctorate in American literature at Stanford. Finding that he had little interest in research, he left the program after finishing a master’s degree.

Returning to Provo from Stanford, Thayer taught in the BYU English Department in 1957-1960, considered studying to be a clinical psychologist, and then started a doctorate in American studies at the University of Maryland. However, still not liking research, he decided that what he really wanted to do was write short stories and novels. He transferred to the University of Iowa, and finished an MFA in fiction writing. During these years, his work experience included helper on a uranium drill rig, construction laborer, railroad section hand, janitor, restaurant dishwasher, insurance salesman, and seasonal ranger in Yellowstone National Park.

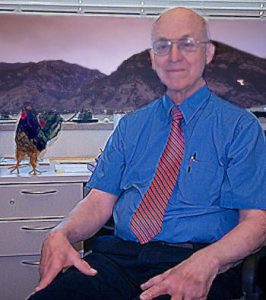

After completing the MFA, Thayer returned to BYU, where he taught fiction writing and other classes until his retirement in 2011. He taught at BYU for a total of fifty-four years. He served as Coordinator of Composition, Director of Creative Writing, and Associate Chair in the English Department and Associate Dean of the College of Humanities.

In 1974, at the age of 45, Thayer married Donlu DeWitt, who was then 26. Doug and Donlu had six children in nine years–Emmelyn, Paul, James, Katherine, Stephen, and Michael. They have twenty-one grandchildren. Donlu attended Brigham Young University as an Honors Program Scholar and Karl G. Maeser Scholar, graduating in 1970 as co-valedictorian of the College of Humanities, magna cum laude, Honors Program High Honors with Distinction, with a double major in French and English. She received a master’s degree in American Literature from BYU in 1972. She worked as an editor for BYU Press and was for many years volume editor for the New World Archaeological Foundation. She taught for the Brigham Young University English Department and Honors Program intermittently during

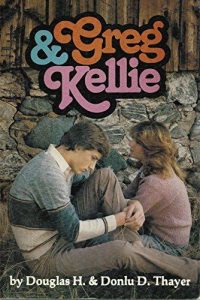

In 1974, at the age of 45, Thayer married Donlu DeWitt, who was then 26. Doug and Donlu had six children in nine years–Emmelyn, Paul, James, Katherine, Stephen, and Michael. They have twenty-one grandchildren. Donlu attended Brigham Young University as an Honors Program Scholar and Karl G. Maeser Scholar, graduating in 1970 as co-valedictorian of the College of Humanities, magna cum laude, Honors Program High Honors with Distinction, with a double major in French and English. She received a master’s degree in American Literature from BYU in 1972. She worked as an editor for BYU Press and was for many years volume editor for the New World Archaeological Foundation. She taught for the Brigham Young University English Department and Honors Program intermittently during  1970–2008. She is the author of two novels, In the Mind’s Eye and The Wall, as well as writing a “Kellie”, a companion piece to Douglas’ short story “Greg”, which was combined into a book and later made into a short movie. In 2004 she graduated from the BYU J. Reuben Clark Law School, where she received the Faculty Award for Meritorious Service. She is a member of the Utah State Bar, and she became a senior editor at BYU’s International Center for Law and Religion Studies.

1970–2008. She is the author of two novels, In the Mind’s Eye and The Wall, as well as writing a “Kellie”, a companion piece to Douglas’ short story “Greg”, which was combined into a book and later made into a short movie. In 2004 she graduated from the BYU J. Reuben Clark Law School, where she received the Faculty Award for Meritorious Service. She is a member of the Utah State Bar, and she became a senior editor at BYU’s International Center for Law and Religion Studies.

Douglas Thayer began publishing short stories in the mid-1960s. Later his writing, along with his colleague Donald R. Marshall, came to be recognized as the start of a new stage in Mormon literature, following the “home literature” which appeared largely in Church-owned journals, and the “lost generation” of Mormon and ex-Mormon authors who wrote for the national market in the mid-20th century. Some of Thayer’s stories appeared in non-Mormon literary magazines, including “The Turtle’s Smile” (Prairie Schooner Fall 1970), which was listed in The Best American Short Stories 1971. The majority, however, appeared in Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, which began publication in 1966, just as Thayer’s career was beginning. The journal’s founding marked the start of an independent Mormon literature community, which encouraged writing on Mormon themes, but largely without a devotional or missionary goal. The combination of new voices with new publication venues can be seen as the start of modern Mormon literature. Thayer has had at least ten stories published in Dialogue, as well as stories in BYU Studies, Sunstone, and Irreantum.

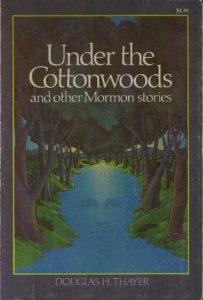

His first collection, Under the Cottonwoods and Other Mormon Stories (1977), was a key work in the development of a new realistic Mormon fiction. He has had two other short story collections, Mr. Wahlquist in Yellowstone (1989), which contained Western stories without any Mormon references, and Wasatch (2011), which was a mixture of older and newer stories. He saw four of his novels published, Summer Fire (1983), The Conversion of Jeff Williams (2003), The Tree House (2009), and Will Wonders Never Cease (2014), as well as a memoir, Hooligan: A Mormon Boyhood (2007). Thayer had largely completed another final novel, which is scheduled to be published by Zarahemla Books.

His first collection, Under the Cottonwoods and Other Mormon Stories (1977), was a key work in the development of a new realistic Mormon fiction. He has had two other short story collections, Mr. Wahlquist in Yellowstone (1989), which contained Western stories without any Mormon references, and Wasatch (2011), which was a mixture of older and newer stories. He saw four of his novels published, Summer Fire (1983), The Conversion of Jeff Williams (2003), The Tree House (2009), and Will Wonders Never Cease (2014), as well as a memoir, Hooligan: A Mormon Boyhood (2007). Thayer had largely completed another final novel, which is scheduled to be published by Zarahemla Books.

While an appreciation of Thayer’s writings has yet to extend nationally, he is highly respected by Mormon literary scholars. Eugene England, the founding editor of Dialogue and later a colleague of Thayer’s at BYU (and a frequent fly-fishing partner), had long been a fervent supporter. He wrote in 1992, “Thayer and Marshall benefitted in their pioneering efforts from two separate influences: they studied modern British and American writers, such as Joyce, Hemingway, Porter, and Flannery O’Connor, and they learned new approaches to Mormon history and culture from the nationally published writers of the lost generation. They also had access to a Mormon audience, critics, and outlets in an expanding intellectual community. They benefitted especially from Clinton Larson, a poet and dramatist who in the 1950s and 1960s became the first Mormon writer to combine excellent contemporary training and natural talent with an informed and passionate faith that he made central to his work . . . As John Bennion has said, “[Thayer] was the first to solve the major problem. He taught us how to explore the interior life, with its conflicts of doubt and faith, goodness and evil, of a believing Mormon.”

England wrote in Dictionary of Literary Biography, soon before his death in 2001, “Douglas Thayer conveys the tragic in American experience that comes from what people and the wilderness have done to each other as well as any contemporary Western writer. From his early story “Red-Tailed Hawk” [England’s favorite Thayer story] through two collections and a novel, and into his latest stories and essays, he displays insight into the particular history of the destructive relationship between mankind and the wilderness in the West, from the arrogant, self-defeating mountain men of the 1830s, intruding into lands and cultures they could not comprehend, to modern men and boys who try, at great cost to themselves and others, to recapture the primitive and merge with wilderness.”

Bruce W. Jorgensen, another BYU colleague, tended to be a bit harder on Thayer than England had been. He wrote in the 1987 article “Romantic Lyric Form and Western Mormon Experience in the Stories of Douglas Thayer” (Western American Literature, 1987), “Thayer’s craft is severe, his style deliberate, chiseled, almost mannered, his tone almost never humorous before the cowboy tall-tales of Summer Fire; his protagonists in the novel and stories alike are upward-mobile Provo boys or men nearly fanatic about righteousness and perfection. As a short story writer, Douglas Thayer seems to have adapted, consciously or otherwise, a major form of Romantic lyric poetry to western Mormon experience and consciousness, but in ways that also question and undercut this form. Thayer’s characteristic strategy in the stories of Under the Cottonwoods, which is to follow the introspective and retrospective processes of a male protagonist through some brief, decisive interval in his life, seems to me a fairly clear translation of what M. H. Abrams has called “the greater Romantic lyric” into the terms of the short story, usually handled in a third-person limited-omniscient or “central consciousness” point of view. This strategy, which may derive most directly from such a story as Irwin Shaw’s “The Eighty-Yard Run” (which Thayer admired and often taught in short story courses in the sixties), so consistently operates in Under the Cottonwoods as to become a sort of signature or hallmark that some readers have found irritatingly repetitive—here’s another “Thayer story.” Insofar as all the stories in the volume do play variations on that strategy, such a response is valid; but perhaps it is also rather like a partially-trained listener’s reaction to a series of string quartets: large similarities of structure and treatment may seem to outweigh subtle differences in texture, key, motif, which only patient re-hearing may disclose . . . Thayer’s later-published stories in Mr. Wahlquist in Yellowstone explore the seductive American myths of “wilderness” from a perspective implicit in LDS theology.”

In his work Thayer treated such topics as pride, grace, redemption, war, hunting and fishing, perfection, materialism, and religious conversion. His stories focused overwhelming on men, particularly young men coming of age, frequently with the backdrop of the Western outdoors. MacEvoy DeMarest has written, “The mountains, rivers and elements of [Thayer’s stories] are maybe more accurately described as characters than as settings. They shape and challenge his protagonists, and in some cases give them their very purpose.”

In recent years, Scott Hales has become one of Thayer’s strongest proponents. In 2012 he wrote, “Thayerian heroes [are] boys who learn all too quickly that the seemingly ordered and secure world around them can also be hostile and unforgiving—even with a loving God in heaven . . . [The stories collected in Wasatch] explore the fragile psyche of Mormon men—arguably Thayer’s uber-theme—through the author’s trademark concise, understated sentences. Absent, however, are the heedless, domineering patriarchs, those stereotypical brutes . . . so prevalent in fiction about Mormons. Thayer’s men feel largely inadequate, wearing their prescribed gender role like an ill-fitting shirt. Or, they feel out of place and time, as if the most important part of their life has somehow slipped away from them, passed unnoticed, leaving them disoriented and nostalgic for the person they once had been . . . Thayer—eighty-three years old and counting—remains a vibrant, relevant force in Mormon fiction. Indeed, I recently had the opportunity to attend a reading where Thayer read and spoke about “Wolves,” one of his finest stories. Hearing him speak about his work, listening to his insights, left me little reason to doubt why he enjoys the reputation that he does. He is twentieth-century Mormonism’s greatest literary chronicler, and the Mormon people–particularly the men he so earnestly and honestly portrays–are better because of him.”

When asked where readers new to Thayer should start, Hales commented, “I’d recommend starting with The Conversion of Jeff Williams, which I think is Thayer’s most accessible and contemporary work–and possibly his best work overall (if it isn’t The Tree House). Hooligans has its moments, but it really is not his best work. The Tree House is excellent, but it has a slow start. Summer Fire is also worth reading, although some readers are put off by the self-righteous narrator. If you haven’t yet read the short stories ‘Wolves’ and ‘The Locker Room,’ I strongly recommend them.”

Thayer’s prizes and awards for his work include numerous Dialogue prizes for the short story and essay, the P.A. Christensen award, the Karl G. Maeser Creative Arts Award, the Utah Institute of Fine Arts Award in the Short Story, a 2011 Whitney Award Lifetime Achievement Award, and six awards from the Association for Mormon Letters. The six AML awards included a 1977 Short Story Award for stories that appeared in Under the Cottonwoods, a 1983 Novel Award for Summer Fire, a 2003 Novel Award for The Conversion of Jeff Williams, and a 2011 Short Fiction Award for Wasatch. He also was given an AML Honorary Lifetime Membership in 1988, and the Smith-Petit Foundation Award for Outstanding Contribution to Mormon Letters in 2008. Thayer’s papers were deposited in the BYU HBLL Special Collections in 2006.

The Deseret News reports that Thayer was diagnosed with terminal lymphoma and given six months to live in November 2015. He defeated the disease but was diagnosed in May 2017 with liver cancer. He passed away at the age of 88.

Below is a bibliography of Thayer’s work, and a selection of reviews of Thayer’s writings.

Bibliography

“His Wonders to Perform” BYU Studies, 6:2, Winter 1965

“The Rooster”. Colorado Quarterly. 16, Fall 1967.

“The Redtail Hawk” Dialogue, 4:3, Autumn 1969. Dialogue prize for imaginative literature, 1969.

“The Turtle’s Smile” Prairie Schooner. 44:3, Fall 1970. Listed in The Best American Short Stories 1971.

“Opening Day” Dialogue, 5:1, Spring 1970. Also republished in Bright Angels and Familiars. [See a Theric-led discussion about the story here.]

“Second South” Dialogue, 5:4, Winter 1970

“The First Sunday” The Ensign, 1:5, May 1971. AKA “Testimony”

“Under the Cottonwoods”. Dialogue, 7:3, Autumn 1972

“The Clinic” Dialogue, 8:3-4, Autumn/Winter 1973

“Zarahemla” BYU Studies, 14:2, Winter 1974

“Ten Years of Laughter”. Sunstone, 1:4, pages 30-36, Fall 1976

“Greg” Dialogue, 10:2, Autumn 1976

Under the Cottonwoods and other Mormon stories. Midvale, UT: Orion Books/Signature, 1977. Republished by Tabernacle Books in 1999.

Greg & Kellie. Salt Lake City, UT: Aspen, 1982. Co-written with Donlu Thayer. 75 pages. The book was adapted into a 1998 movie, Only Once, directed by Rocco DeVilliers.

Summer Fire. Midvale, UT: Orion Books/Signature, 1983

Mr. Wahlquist in Yellowstone. Salt Lake City, UT: Gibbs Smith, 1989

“Brother Melrose”. Dialogue, 32:3, Fall 1999

“Ice Fishing.” Dialogue 33:2, Summer 2000

Interview with Doug Thayer. Irreantum, 4;3, Autumn 2002

“A White House”. Irreantum, 4:3, Autumn 2002. An excerpt from The Conversion of Jeff Williams

“Wolves”. Dialogue 36:2, Summer 2003. Republished in Dispensations, 2000

The Conversion of Jeff Williams. Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2003

“Carterville”. Dialogue. 38:1, Spring 2005

Hooligan: A Mormon Boyhood. Provo, UT. Zarahemla Books, 2007. Memoir

2007 Times and Seasons interview, by Russell Arben Fox

The Tree House. Provo, UT: Zarahemla Books, 2009

“The Locker Room”. Irreantum. Fall/Winter 2010

Wasatch: Mormon Stories and a Novella. Zarahemla Books, 2011

Will Wonders Never Cease: A Hopeful Novel for Mormon Mothers and Their Teenage Sons. Zarahemla Books, 2014

Reviews of Thayer’s publications

Under the Cottonwoods and other Mormon stories. Midvale, UT: Orion Books/Signature, 1977.

Under the Cottonwoods and other Mormon stories. Midvale, UT: Orion Books/Signature, 1977.

The full text is available online, care of Signature Books.

Edward Geary, Dialogue. “The stories will speak more powerfully to members of the Church than to others. Powerfully, but not reassuringly; for Thayer’s book is a kind of Mormon Dubliners, examining the moral and spiritual paralysis of Mormon lives in ways that most of us, I think, will find rather uncomfortable. The resemblances to Joyce’s Dubliners are extensive enough to suggest an influence. All of the characters inhabit one provincial town, in this case Provo, Utah. The stories, though separate, gain additional meaning and impact when read as a group, and they are arranged roughly in order of the advancing age of the protagonists. The stories have little action in the usual sense, depending instead for their effect on developing insight.”

Wm Morris, A Motley Vision. “The short stories are definitely Mormon — very Mormon, very male, very Provo. All of them feature male characters — many of them age 18-22– who live or grew up in Provo in the ’50s, ’60s or ’70s. I suppose one could fault Thayer for this narrow focus, but I would argue that the results testify to the power of concentrating one’s creative efforts on one slice of life, for collectively these stories powerfully capture an important aspect of Mormon culture — the joys and costs of the burden of expectations that Mormon men (especially young men) are expected by their families and wards to carry . . .The best story of the lot is “Elder Thatcher.” The entire narrative takes place as the returned missionary of the title sits on the stand in sacrament meeting and thinks about his mission and what he’s going to say to the congregation, struggling with whether or not to give them the values-affirming, standard RM, welcome home talk that they all expect or do what a disaffected, bitter RM had challenged him earlier that day to do — to “not tell more lies” than he has to. The power of the story is that as Elder Thatcher, who went on his mission because that was what they (his family, his ward) had all expected of him, unsure of his testimony, recalls the reality of his mission — the homesickness, the doubts, the elders who tortured themselves with memories of home or who fought or who didn’t do work, the elders who had strong testimonies and worked hard, the members in Germany where he served, the feeling that his body was aging, that he was losing two years of his youth and vitality, the unresponsive people who answered the door and stared blankly at them when they said they were messengers of Christ — it becomes apparent that he has truly gained a testimony, a living testimony.”

Summer Fire. Midvale, UT: Orion Books/Signature, 1983.

Summer Fire. Midvale, UT: Orion Books/Signature, 1983.

Edward Geary, BYU Studies 24:2, 1984. “Summer Fire, like his earlier volume, Under the Cottonwoods, represents an experiment to determine whether Mormon values can be subjected to the scrutiny of serious fiction, not from the standpoint of partial or complete alienation (as has been the case with much serious Mormon fiction in the past) but from a moral position firmly within the LDS framework. For this reason, even though his work is formally quite conventional, Thayer may be the most innovative writer in Mormon letters today.”

Eugene England, Dialogue. “The first “real” Mormon novel in nearly thirty years, that is, the first to deal seriously with Mormon characters and ideas and to use them to create versions of the central human conflicts that energize good fiction.”

Scott Hales: “Douglas Thayer’s fiction clings doggedly to the Mormon boyhood. His protagonists, usually young men from Provo, exist in a limbo state between innocence and knowledge. Indeed, like adolescent Adams, they often bite into forbidden fruits—usually violent in nature—and find themselves stranded in lone and dreary worlds. In this respect, they share blood—in more ways than one—with the protagonists in the fiction of Ernest Hemingway and Cormac McCarthy, two writers whose works famously explore the ways violence shapes masculinity. But where the protagonists of Hemingway and McCarthy succumb to the violence of a fallen world, Thayer’s hold on to the possibility of joy and redemption, even when neither possibility is readily discernible . . When the day comes that I teach an Introduction to Mormon Literature class to a room full of Latter-day Saints, I’m going to assign Summer Fire. Not only has Thayer written the novel in an incredibly teachable way—it employs traditional plot structure, a clear theme, and plenty of accessible symbolism—but he has also used it to address many of the basic doctrines (i.e. atonement, eternal progression, etc.) that young Latter-day Saints learn about and discuss in the Seminary program. What is more, the novel has a kind of ageless quality about it, despite being set sometime in the mid-1960s, possibly due to its remote setting, timeless themes, or even Thayer’s own distinctive, unadorned prose style. Whatever the case may be, readers are unlikely to be distracted by any details that would betray the fact that it was published nearly thirty years ago. Summer Fire, in short, is an excellent novel that deserves recognition as a classic of Mormon fiction.”

Mr. Wahlquist in Yellowstone. Salt Lake City, UT: Gibbs Smith, 1989.

Mr. Wahlquist in Yellowstone. Salt Lake City, UT: Gibbs Smith, 1989.

Kirkus: “Five long stories, mostly about hunting men or solitaries who are ill at ease in family and society. All take place in the West: four are roughly contemporary, while one is a more traditional western, but all five render a harsh landscape where humans at best survive . . . Thayer is skillful at using place to develop character . . . Like the poet Robinson Jeffers, Thayer is interested primarily in hawks and rocks, and in how nature tests men (and, occasionally, a woman). His book is notable on those terms.”

Eugene England, Western American Literature. “Douglas Thayer’s stories offer the most powerful examination I have seen of the consequences of our continuing destructive relations to wilderness, and gently point to some alternatives in mature, family- and community-centered living. Thayer grew up in the Rockies, like some of his protagonists, as a deadly little white savage, killing whatever wildlife he could, running wild and swimming naked along the margins of Mormon villages. His conversion came through education and writing and the maturing of his own Mormon faith. He studied at Stanford under Yvor Winters, perhaps the most powerful modern voice against Romantic optimism—and blindness—about nature. His stories reveal a constant and increasingly successful effort, as Bruce Jorgensen has shown, to adopt the major Romantic lyric form, a self-educative meditation in or upon a wilderness setting, “to western Mormon experience and consciousness, but in ways that also question and undercut this form.” Though the stories in Mr. Wahlquist in Yellowstone have been written over a twenty-five year period, they are more closely connected in theme and are more logically arranged than those in Thayer’s earlier collection, Under the Cottonwoods’, they also reflect more precisely the quality of Thayer’s own spiritual journey.”

The Conversion of Jeff Williams. Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2003.

The Conversion of Jeff Williams. Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2003.

Publisher’s summary: Provo is a world away from San Diego. In this topsy-turvy tale, it is the wealthy, religious, east-bench Provoans who enjoy the best that life can offer and share it with a less privileged, laid-back, So Cal teenager over one summer vacation. At first, Jeff finds himself dazzled by east-bench affluence and faith. But as the summer progresses, events persuade him to rethink this religion-and-riches culture and to accept that the normal temptations and foibles of youth—without the Porsche—are just fine: “Every September before school, Dad gave me a blessing and told me to be receptive to the guidance of the Holy Ghost. I didn’t particularly like the idea of the Holy Ghost following me around, checking up on what I was doing all the time, but Mom said I needed all the help I could get, particularly when it came to girls. I liked living in Aunt Helen’s eight-million-dollar house. It made me feel like I might enjoy the summer more than I had thought I would. I knew that I wouldn’t be able to wander around the house in my boxers and t-shirt, but I felt important.”

Richard Cracroft: “This landmark novel is the finest fictional exploration to date of growing up humanly and mormonly. [It is] clearly the best coming-of-age novel in Latter-day Saint literature . . . It is a tender and moving love song to spirituality and a Mormon world view.”

Todd Peterson, Dialogue. “Douglas Thayer’s latest novel, The Conversion of Jeff Williams, delineates the elite of Provo in strokes that scream “pride cycle of the Nephites.” While Thayer clearly wants us to see the great spaciousness of the houses on the hill, he does his best to make sure we know that the rich have feelings too, that they are multi-dimensional and maybe not the phonies we working stiffs think they are. [Peterson is critical of Thayer’s uneven and overly forgiving treatment of the rich Provo family.] However, plot and character development are not the main features of this book: it’s the writing. The beauty here is to be found in its pacing and textures. If it were a film, The Conversion of Jeff Williams would be more like Lost in Translation than The Bourne Supremacy. In fact, the slowness and indirection of this novel might put off readers who prefer books that are a little more skimmable. Thayer doesn’t give us a plot so much as he gives us the conditions of this young man’s life over a few months, and by the end he’s converted. No trumpets, just life as it happens. Thayer’s prose has a honed haiku-like austerity to it, which is engaging and refreshing. He also makes a number of dead-on observations about Mormon culture. For example, during one of Jeffs ruminations on the Mormon drive for large families, he quips, “If you showed up in a restaurant in San Diego with ten or twelve kids, they would probably arrest you”.

Hooligan: A Mormon Boyhood. Provo, UT. Zarahemla Books, 2007.

Hooligan: A Mormon Boyhood. Provo, UT. Zarahemla Books, 2007.

Richard Cracroft: “Thayer’s delightful memoir about growing up Mormon in the Sixth Ward of Provo, Utah, in the 1930s and ’40s will be, mark my oh-so-sagacious words, an LDS classic. Growing up in pre-industrial, impoverished, pre-Second World War simplicity, with fishing pole in one hand, a .22 in the other, and oodles of unsupervised free time on both hands, young Thayer became a keen-eyed observer of small-town Mormon life. But Hooligan is more than rich nostalgia about a bygone era (although it is that); it provides delicious insight into the mystery of growing up with its inevitable losses and gains; it is a front seat on the timeless journey of Innocence to Experience. Young Douglas, determined to add a “Perfect Boy” pin to his Eagle Scout badge, runs, again and again, into the ironic brick wall between the wannabe Ideal Boy and the Real Boy. The result is a book fraught with wise, comical, ironical observations about the human condition, a wonderful book which will be treasured only by those who have ever been young (and seeking perfection) and aren’t anymore (as much). As I said, it’s an instant classic that you’ll find yourself reading aloud to others of your ilk.”

Darlene Young: “The biggest strength of the book is that although all of the reminiscences are firmly grounded in sensory details, I can still pick up the overarching feelings of what it’s like to be a child, new to the world and its philosophies. Thayer accurately and movingly conveys both the joys of childhood (swimming at night with water and moonlight sliding over your skin, sitting by the coal stove in winter) and it’s perplexities and loneliness. Especially moving to me is the aching of this small boy for a father who would take him hunting. Thayer’s genius is in never saying, ‘I was sad about that,’ but we feel it through his memories of watching the other boys go off with their fathers.”

Edward Geary, Dialogue 41:2. “A staple of Douglas Thayer’s fiction is the sensitive, adolescent or young adult Mormon male struggling to come to terms with the burdens of mortality, a sense of sin, or the pressures of exemplary living. Now, in a memoir, Thayer deals more directly with his own experiences of growing up in the old Provo Sixth Ward during the 1930s and ’40s. Curiously, the authorial voice in the memoir is almost entirely devoid of the complicated inner life of Thayer’s fictional protagonists. He maintains a cool, rather detached, faintly ironic narrative tone throughout, with only oblique hints at something more deeply involved.”

2007 Times and Seasons interview, by Russell Arben Fox. Thayer expressed his pessimism for the future of Mormon literature. “Certainly I see some very talented writes in our writing students here at BYU, some of whom are publishing nationally (mostly fantasy and young adult fiction), but not Mormon stuff. National publishers still don’t seem particularly interested in Mormon fiction, but maybe that will change with Mitt Romney running for president, the new film on the Mountain Meadows massacre, and the recent PBS series on Mormonism, but maybe not. I don’t see the appreciative audience growing particularly. From what I’ve heard, the Dialogue, Irreantum, and Sunstone subscription lists stay about the same, if that’s an indicator. Mormons aren’t clamoring for good literature; never have and never will, as far as I can see . . . I write what I want to write, but then I have no desire to shock my readers. I like to think that what I write makes sense, is insightful, skillfully done, and perhaps even true, and entertaining. I write about somewhat ordinary, faithful Mormons living their contemporary lives, people who stay in the Church, whatever their inclinations otherwise. Their lives aren’t aberrant, so their isn’t much to censor, but much to understand and portray . . .Does Mormonism “have” artists? Never really considered the possibility, unless in some odd way Mormonism has what it doesn’t really want or need; assuming, of course, that such a thing as Mormonism exists to begin with. No, Mormonism isn’t hard on its artists; the artists are hard on themselves. Filled with self-importance and a need to suffer, they exaggerate their worth, as far as Mormonism is concerned, although they may be worth a great deal otherwise, maybe.”

The Tree House. Provo, UT: Zarahemla Books, 2009.

The Tree House. Provo, UT: Zarahemla Books, 2009.

Publisher Blurb: When Harris Thatcher’s father dies, the boy’s journey into manhood becomes complicated with questions of faith, the meaning of life, and the capriciousness of death. Harris soon finds himself preaching the Mormon gospel as one of the first missionaries to West Germany following the devastation of World War II. Little does he know that his own war horrors await him upon his return home, when he is drafted into the Korean War. Starting out in the same 1940s-era Provo, Utah, that Thayer brought to life in his memoir Hooligan: A Mormon Boyhood, this novel deepens and darkens as Harris is drawn into his harrowing Korean ordeal. Will he survive the war, not only physically but also emotionally and spiritually? And if he does survive, what other trials does death hold in store?

Scott Hales: “Few writers have chronicled the experience of the Mormon man better than Douglas Thayer. The Tree House, is a tough, gritty novel about a young man’s run through the gauntlet of tragedy — first in the seemingly idyllic neighborhoods of 1940s Provo, then in the cynical streets of post-war West Germany, and finally in the numbing hell of the Korean War. It’s a gripping study on the loss of innocence, idealism, and certainty, and Thayer pulls no punches in its delivery . . . It is the single best example we have of Mormon missionary fiction.”

Elouise Bell: “The Tree House ranks with The Red Badge of Courage in its creation of the ghastly bubble inhabited by a soldier in battle. Claustrophobic, electrified by panic, astonishingly intimate, Thayer’s chapters on war have a power we have not seen from him before. There is not a shred of moralizing here, yet the book nourishes the soul from start to finish.”

Richard Cracroft (BYU Magazine): “In content, style, and tone, The Tree House recalls the stoical eloquence of Ernest Hemingway and becomes a kind of Mormon update of A Farewell to Arms . . . As a Mormon missionary novel, The Tree House is better than anything we’ve had so far. As a story of soldiers-at-war, the novel captures the numbing terror of trench warfare in Korea with an immediacy that recalls Stephen Crane’s The Red Badge of Courage. Thayer’s third and best novel is splendidly crafted stick-to-the-soul literature.”

Daily Herald: “In his signature quiet, luminous prose, Thayer takes us and Harris from there through Harris’s young life: He gets a job washing dishes and making pies at the Starlite Cafe; falls in love with Abby; sees Luke off on his mission and goes himself, to postwar Germany. He likes studying German and becomes fluent; he is a good missionary, working hard and patiently teaching the elders who are flaky or lazy . . . Harris Thatcher is a young man who will stay with the reader a long time, not just because he himself becomes so dear through the course of the narrative, but because we all know someone like him — a son, a brother, a friend — someone who loves deeply but warily, always holding a little of himself back for fear of or in deference to something he can’t quite name. The Tree House is a lovely, elegiac work, a treasure of our own time and place.”

Wasatch: Mormon Stories and a Novella. Zarahemla, 2011.

Wasatch: Mormon Stories and a Novella. Zarahemla, 2011.

Laura Wadley, Daily Herald: “The book begins with “The Red-Tailed Hawk,” the classic story of a young man whose desperate need for solitude nearly kills him. “Brother Melrose” is a wryly funny ghost story about a high priest come back from the dead.” “Crow Basin” is a painfully beautiful story about an unbelieving doctor confronting tragedy with a group of Scouts in the mountains, and “Yellowstone Country” tells the story of Philip, a young husband and father seemingly trapped in a middle-class, suburban, boring life who yearns for something more, but who doesn’t quite know how to deal with what comes when he gets it. The darkly glittering jewel of this collection, though, is “The Locker Room,” a deeply disturbing, deeply nuanced story about what is truly good and what is merely right. Themes of wildness and safety inform “Dolf,” the book’s novella, where Thayer turns the story of John Colter’s run on its head as a young Rhode Islander really means to heed his mother’s desire for him to “return to Providence,” but who in the end cannot go back. Believing members of the LDS Church and the women (especially wives and mothers) in Thayer’s stories are caricatures of constraint, but the men are brought brilliantly to life. They all “would rather have the iceberg than the ship,” in Elizabeth Bishop’s telling phrase, “although it meant the end of travel.”

MacEvoy DeMarest, Shelf-Actualization. “On the face of it, you could say that Thayer is firmly entrenched in telling only one kind of story, as almost all of these selections feature coming of age tales told from the perspective of the Mormon male. But to dismiss the collection on those grounds would be to do the author and the reader a great disservice. There’s considerable range lurking beneath the surface. Whether it’s the magical realism of “Brother Melrose,” or the black comedy of “The Gold Mine,” Thayer explores themes of life and death, survival and forgiveness, faith, doubt, friendship, heroism and more. Thayer’s Mormon-ness, which is altogether absent in a number of the stories, is doled out by varying degrees in the interior monologue of his characters, rather than explained overtly in sermons and worship services. Sometimes this method gives an air of expository doctrine dropping (as in “Crow Basin” and “Apache Ledges”), but for the most part it is handled deftly- as a backdrop or a motivation for the character action. In fact, those stories that delve for deeper religious meaning (“The Locker Room” and “Fathers and Sons”) are among the most powerful in the collection. The author has described himself as having “a mind that deals in images.” His straightforward prose certainly conveys those images clearly, and above all, evokes a strong sense of place. The mountains, rivers and elements of Wasatch are maybe more accurately described as characters than as settings. They shape and challenge his protagonists, and in some cases give them their very purpose . . . Thayer moves effortlessly between backstory and present action in all of his stories, but does so to special effect in his novella “Dolf,” which will have your heart pounding right up until not one, but two final twists knock you squarely between the eyes. It’s like something out of Cormac McCarthy or the very best Louis L’Amour.”

Kathryn Lynard Soper, BCC: “Wolves,” a surprisingly brutal yet ultimately transcendent story written by BYU’s Douglas Thayer. This account of a young man victimized by post-WWII transients effortlessly carried me from the depths of violence (implied, not described) to the heights of redeeming love. It hurt to read, but it healed its own wounds.”

Will Wonders Never Cease: A Hopeful Novel for Mormon Mothers and Their Teenage Sons. Zarahemla Books, 2014.

Will Wonders Never Cease: A Hopeful Novel for Mormon Mothers and Their Teenage Sons. Zarahemla Books, 2014.

Publisher blurb: Weeks away from turning sixteen, Kyle Hooper longs to get his license and (legally) drive the old Suburban his Grandpa Hooper left him. Sardonic, light-hearted, a prankster, Kyle wants more freedom in his Colorado Mormon life, including the freedom to date any number of lovelies, as he calls them. His mother, Lucille, a part-time trauma nurse and a devoted Mormon mom, wants Kyle to get serious about school and preparing for his mission. In vivid detail she often warns him about the consequences of a misspent youth—drug addiction, arrest and imprisonment, expulsion from school, early marriage to a pregnant girlfriend, poverty, STD, alcoholism, highway death. Filled with missionary zeal, Lucille works to bring Mark, Kyle’s best friend, to the waters of baptism. Disobeying his mother one Saturday morning, Kyle, driving unlicensed, heads for the ski slopes. In Silver Canyon an avalanche sweeps his Suburban off the road. Trapped but getting air, grateful for the two roll bars Grandfather Hooper installed, Kyle knows he has to dig an escape shaft or die. Exhausted, starving, freezing, he begins to understand what his mother has been trying to teach him about the need for faith.

Scott Hales, A Motley Vision. “Loyal readers of Douglas Thayer’s fiction will not be surprised—at least initially—by his latest novel. For the last half-century, Thayer has been writing stories about young Mormon men, still naïve in the faith, whose battles with wilderness and human nature leave them emotionally and physically scarred, yet also hopeful and spiritually more mature. His protagonists are not the guilt-drenched youths of Levi Peterson’s fiction, whose forbidden experiments with sin and sex leave them feeling acutely the classic division between body and spirit. Instead, they are sensitive, righteous young men who take beating after beating from a world where God observes more than he intervenes. Thayer’s protagonists are acquainted with death, cruelty, and injustice. If anything redeems them, makes them willing to hope, it is their awakening to grace and the strong influence of their mothers . . . Will Wonders Never Cease is a typical Thayer coming-of-age story, yes, but it urges us to resist reading it as such. This is no small challenge, however, because, unlike Thayer’s other works, this new novel feels claustrophobic with its intense focus on the plight of the main character. Trapped in the Suburban, Kyle has very little to see and nowhere to go except to where his imagination takes him. Consequently, readers spend hardly any time away from Kyle, especially since his interactions with other characters, as played out in his memories, are generally vignette-length. Readers must work to dig their own way out of the snowpack of Kyle’s narrative voice—at least if they want a fresh experience with Thayer’s fiction. Will Wonders Never Cease is essentially a story about a mother’s love for her son, but unless you choose to read it that way, you likely miss that point. And what if you do miss it? I think you’ll still find a novel worth reading, although not one that trumps any of Thayer’s earlier novels. With The Tree House, Thayer delivered his masterpiece and I doubt any follow-up novel will ever rival it. Thayer, after all, turned 85 this year and has perhaps already produced the best work of his career. Reading Will Wonder Never Cease, I also felt as if Thayer’s connection to contemporary life was fading. While Kyle and his friends are modern teens, they talk as if they belong in mid-century . . . Despite these relatively minor issues, Will Wonders Never Cease is another worthy contribution from the pen of Douglas Thayer.”

Doug Gibson, Ogden Standard-Examiner. “Thayer is probably one of the top five or six Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints novelists out there and his newest is a good read that mixes an adventure with the protagonist’s stream of consciousness, thinking as he works to avoid peril and death . . . Kyle is a well-developed character of Thayer’s and the reader will enjoy following along with his ingenious and courageous efforts to save himself from what looks like a long, prolonged and certain death . . . Three characters are well-formed by Thayer, an author in his 80s. Kyle’s mother, Lucille, who is originally perceived as a Mormon scold but is revealed to be refreshingly progressive on issues such as homosexuality and premarital pregnancy, and possessed of a strong will, his Grandpa Hooper, whose legacy of common sense and handyman’s know-how is used to great advantage by Kyle . . . About the only thing I don’t like about this novel is the bland title, which seems more suitable for self-help or inspirational genres. But it’s a good read, compelling and thought-provoking and readers — drawn into Kyle’s plight — won’t be able to put the book down in the final pages.”

Many parts of this post were taken from the biographical sketch on Thayer’s website, today’s Deseret News obituary, and a biographical sketch of Donlu from BYU’s J. Reubun Clark Law School.

Saddened to hear of Brother Thayer’s passing. One of the greats of Mormon Literature. His UNDER THE COTTONWOODS volume is one of the most important works of Mormon Literature, certainly of those published during my lifetime. It is a book I have gone back to over and over again. I treasure the few brief interactions I had with him at AML and on campus.

.

Of course, he’s been old a long time, but it’s still hard to take. I only met him a couple times (though there was a brief time I knew Donlu rather well), but his best short stories are as good as any of his contemporaries.

Margaret Blair Young wrote a wonderful personal tribute here: http://www.patheos.com/blogs/welcometable/2017/10/tribute-douglas-heal-thayer-april-19-1929-october-17-2017/

It is interesting to see how productive he became late in life. He wrote a fair number of stories in the 1960s through the 1980s, but published very little in the 1990s. Then after 2000, in his 70s and 80s, he published three novels, a memoir, and several of his best short stories. And there is another novel that he was doing his final edits on.

The (Provo) Daily Herald obituary, which adds some nice personal and Provo touches. http://www.heraldextra.com/lifestyles/announcements/obituaries/douglas-heal-thayer/article_676cd492-7d74-5d53-8b86-5e3dc2092197.html