In Hollywood but Not of Hollywood: Cecil B. DeMille, Paul Schrader, and the Evolving Spiritual Aesthetic of the Institutional films of the LDS Church, Part 1

Mark T. Lewis

[This is the first part of an article taken from Mark T. Lewis’s 2016 Masters Thesis, from Brigham Young University’s Department of Religious Studies, entitled “An Hungry Man Dreameth”: Transcendental Film Theory and Stylistic Trends in Recent Institutional Films of the LDS Church”.]

“It shall even be as when an hungry man dreameth, and, behold, he eateth; but he awaketh, and his soul is empty: or as when a thirsty man dreameth, and, behold, he drinketh; but he awaketh, and, behold, he is faint, and his soul hath appetite” (Isaiah 29:8).

To the religiously minded, few things carry greater importance than a connection to the Divine. For centuries the literature of prophets and the work of gifted artists have served to create a liminal space where man and Maker can meet. As technology and art have advanced, new opportunities for communion have been unveiled. The advent of cinema and the creation of the Internet pose unique questions for the artist seeking to lead an audience toward an encounter with God. Evangelists like Cecil B. DeMille and theologians like Paul Schrader both see the opportunities presented by cinema to stir viewers towards transcendence. However, the aesthetic, or overall stylistic efforts, of DeMille and Schrader differ markedly and reveal a fruitful point of tension: a filmmaker’s portrayal of the spiritual on film reveals much about his or her beliefs about God, the viewer, and how the two achieve correspondence.

As an institution, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has been heavily involved in using film and new media to further its spiritual ends, generally favoring the style of missionaries like DeMille. Comparing the DeMillian aesthetic for spiritual filmmaking and Latter-day Saint beliefs about how man and God communicate reveals spiritually rewarding areas for stylistic exploration in institutional films of the LDS Church.

As an institution, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has been heavily involved in using film and new media to further its spiritual ends, generally favoring the style of missionaries like DeMille. Comparing the DeMillian aesthetic for spiritual filmmaking and Latter-day Saint beliefs about how man and God communicate reveals spiritually rewarding areas for stylistic exploration in institutional films of the LDS Church.

Aesthetic of Cecil B. DeMille

In Cecil B. DeMille’s entire body of work, his “religious epics”—such as his 1956 masterwork, The Ten Commandments—were by far the most impressive and presented the most enduring impact.[i] In these cinematic behemoths, DeMille employed nearly anything that would draw in viewers and slacken their jaws to fuel box-office receipts and drive home his message. To effect this spectacle, DeMille expended copious budgets to hire casts of thousands, depict salacious pagan revels, feature barely clad women,[ii] construct enormous sets, create ornate costumes, wield the full force of technological sophistication for special effects, and score his works with booming soundtracks. DeMille’s films are the cinematic equivalent of what the military would refer to as a “shock-and-awe” campaign. Critics groaned, but audiences flooded in by the millions.[iii] Emboldened by the box office, DeMille ignored his detractors and pressed forward. He had the world’s attention, which, to DeMille, was victory.[iv]

The spectacle of DeMille’s films—pagan, technological, sexual, or otherwise—was always followed by his intended message: “a last-reel affirmation of traditional morality.”[v] The paradoxical juxtaposition of titillation and piety did not go unnoticed. In response to objections concerning his abundant use of sexual imagery, DeMille replied that he was “a firm believer in showing sin in action in order to effectively condemn it.” For him, the moral end could justify the risqué means.[vi] One thing that is certainly to DeMille’s credit was his guilelessness—his morality and his didacticism were not adopted in an effort to please the crowds, even if his use of sexuality seemed to be.[vii] DeMille saw himself in something of a missionary role, garnering interest for biblical topics in a world growing uninterested with scripture.[viii] He clearly outlined what he saw as his Christian and millennial duty as a filmmaker:

The spectacle of DeMille’s films—pagan, technological, sexual, or otherwise—was always followed by his intended message: “a last-reel affirmation of traditional morality.”[v] The paradoxical juxtaposition of titillation and piety did not go unnoticed. In response to objections concerning his abundant use of sexual imagery, DeMille replied that he was “a firm believer in showing sin in action in order to effectively condemn it.” For him, the moral end could justify the risqué means.[vi] One thing that is certainly to DeMille’s credit was his guilelessness—his morality and his didacticism were not adopted in an effort to please the crowds, even if his use of sexuality seemed to be.[vii] DeMille saw himself in something of a missionary role, garnering interest for biblical topics in a world growing uninterested with scripture.[viii] He clearly outlined what he saw as his Christian and millennial duty as a filmmaker:

We in the Industry hold great power. Who else—except the missionaries of God—has had our opportunity to make the brotherhood of man not a phrase, but a reality—a brotherhood that has shared the same tears, dreamt the same dreams, been encouraged by the same hopes, inspired by the same faith in man and in God, which we painted for them, night after night, on the screens of the world? Our influence must be used for good—for truth, for beauty, and for freedom.[ix]

DeMille saw himself as a proselytizer in the truest sense, and he saw his films as propaganda in a grand effort to convert the world. Paul Schrader, a filmmaker and theorist with an eye towards intentionally “spiritual” works, notes a typical example of DeMille’s modus operandi from The Ten Commandments (1956):

In the title scene Moses is on Mount Sinai and God is off-screen to the right. After some premonitory thundering, God literally pitches the commandments, one by one, onto the screen and the awaiting blank tablets. The commandments first appear as small whirling fireballs accompanied by the sound of a rushing wind, and then quickly—building in size all the while—zip across the screen and collide with the blank tablets. Puff! The smoke clears, and the tablet is clearly inscribed.[x]

In DeMille’s missionary logic, there could be little question regarding the origins of the Ten Commandments—the audience had just seen them appear on tablets of stone as they were spoken by the voice of God himself. Using sophisticated special effects, DeMille sought to lend a sense of reality to spiritual mythology by depicting the miraculous as it “really” might have occurred.[xi] What a viewer sees on film appears real; therefore, if the works of God are depicted on film, they too are conceivably real.[xii] The filmgoer’s temporary suspension of disbelief, DeMille may have hoped, would carry beyond the closing credits, quieting doubts and engendering faith. Through the miracle of cinema, entire theaters are able to witness the miracles of Moses and Jesus and become more ardent believers—or, if an unbeliever, to behold the inexplicable and be convinced of the awesome reality of the Divine.

In DeMille’s missionary logic, there could be little question regarding the origins of the Ten Commandments—the audience had just seen them appear on tablets of stone as they were spoken by the voice of God himself. Using sophisticated special effects, DeMille sought to lend a sense of reality to spiritual mythology by depicting the miraculous as it “really” might have occurred.[xi] What a viewer sees on film appears real; therefore, if the works of God are depicted on film, they too are conceivably real.[xii] The filmgoer’s temporary suspension of disbelief, DeMille may have hoped, would carry beyond the closing credits, quieting doubts and engendering faith. Through the miracle of cinema, entire theaters are able to witness the miracles of Moses and Jesus and become more ardent believers—or, if an unbeliever, to behold the inexplicable and be convinced of the awesome reality of the Divine.

Alternative Aesthetics

Chief among DeMille’s detractors is Paul Schrader, who has written and innovated extensively to further his own perspective on spiritual filmmaking.[xiii] Schrader is harsh in condemning DeMille’s techniques and describes the assumptions governing DeMille’s aesthetic as “logical but mistaken.” Schrader suggests that DeMille’s aesthetic is based on an incorrect “notion about the relation between cinematic and spiritual reality.”[xiv] Simply because something appears real, or photo-realistic on film, does not mean that what is seen on film becomes personal reality for the viewer.[xv] The danger, Schrader asserts, is that Hollywood’s and DeMille’s propensity to bluntly depict the miraculous for the viewer to see may lead audiences to confuse the sensual for the spiritual—making spectators of religious films into sign seekers.

Chief among DeMille’s detractors is Paul Schrader, who has written and innovated extensively to further his own perspective on spiritual filmmaking.[xiii] Schrader is harsh in condemning DeMille’s techniques and describes the assumptions governing DeMille’s aesthetic as “logical but mistaken.” Schrader suggests that DeMille’s aesthetic is based on an incorrect “notion about the relation between cinematic and spiritual reality.”[xiv] Simply because something appears real, or photo-realistic on film, does not mean that what is seen on film becomes personal reality for the viewer.[xv] The danger, Schrader asserts, is that Hollywood’s and DeMille’s propensity to bluntly depict the miraculous for the viewer to see may lead audiences to confuse the sensual for the spiritual—making spectators of religious films into sign seekers.

Schrader feels this habit of displaying the miraculous misleads viewers into thinking they can achieve spirituality vicariously; that watching spiritual events, convincingly rendered in moving pictures, will translate into authentic spiritual history. Rather than seeking a personal spiritual experience—what Schrader calls transcendence—the viewer merely assumes, emotionally, the experiences of the person portrayed and resumes his or her life touched by sentiment, but not by the supernatural. Merely identifying with the sufferings of a cinematic Christ, for example, is insufficient. In such a scenario, asserts Schrader, the film “has not lifted the viewer to Christ’s level,” but rather “has brought Christ down to the viewer’s.” Schrader feels that a spiritual film must lead those watching to “a confrontation,” or encounter, “between the human and the spiritual” on their own and that cinematic spectacle would only serve to interfere with an authentically transcendent experience.

Weary of DeMille’s cinematic abundance, Schrader believes in a sort of “stylistic austerity,” involving “limited camera movement and montage, narrative simplicity, elliptical editing, and natural sound.”[xvi] This reveals Schrader’s underlying assumption: that if the film itself is too emotionally satisfying as a result of the rich visual style, the evocative music, or the inviting performances, the audience will never look “beyond” the film for fulfillment.[xvii] They will be led to “mistake sentimentality for spirituality.”[xviii] Conversely, Schrader theorizes that a certain level of cinematic asceticism would allow the film to get out of the way and enable the viewer to be presented with the Divine independent of the film itself. This is perhaps the strongest feature of Schrader’s approach—its implicit confidence in God and man. DeMille sought to mass distribute spirituality. Schrader believes that, if given the proper invitation, an individual will actively seek the spiritual and God will be there to greet him.

Mormon Aesthetics

Because of DeMille’s popular success in religious topics, many sought to follow his formula, the Latter-day Saints among them. Through the 1920s and the decades that followed, the LDS Church worked tirelessly to attract talent from Hollywood to assist in its media proselytizing endeavors.[xix] Thus many early Church productions aimed to quench the thirst for converts by drawing from the aesthetic well of Hollywood; and as far as religious films went, that generally meant Cecil B. DeMille. The Testaments of One Fold and One Shepherd (2000), the second feature-length institutional film created by the LDS Church, was the pinnacle of DeMillian filmmaking for the Church. “The scale was mammoth; it remains the largest production the Church has ever undertaken.”[xx]

Because of DeMille’s popular success in religious topics, many sought to follow his formula, the Latter-day Saints among them. Through the 1920s and the decades that followed, the LDS Church worked tirelessly to attract talent from Hollywood to assist in its media proselytizing endeavors.[xix] Thus many early Church productions aimed to quench the thirst for converts by drawing from the aesthetic well of Hollywood; and as far as religious films went, that generally meant Cecil B. DeMille. The Testaments of One Fold and One Shepherd (2000), the second feature-length institutional film created by the LDS Church, was the pinnacle of DeMillian filmmaking for the Church. “The scale was mammoth; it remains the largest production the Church has ever undertaken.”[xx]

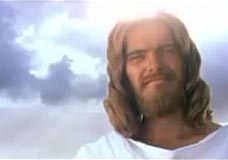

The similarities between The Testaments and DeMille’s The Ten Commandments are considerable.[xxi] Most importantly, however, Testaments pays homage to DeMille in its manner of presenting spiritual events. The closing scene of the film is an excellent example of this. Using a point-of-view shot, the viewer is led to identify with a fictional Book of Mormon man who is healed of his blindness by Jesus during his appearance to the ancient Americans.[xxii] After the man is miraculously granted vision, the audience sees the man’s first sight from his perspective: the smiling face of Jesus. In true Hollywood fashion for the emotional climax of a film, the music swells and the film fades to its epilogue.

The similarities between The Testaments and DeMille’s The Ten Commandments are considerable.[xxi] Most importantly, however, Testaments pays homage to DeMille in its manner of presenting spiritual events. The closing scene of the film is an excellent example of this. Using a point-of-view shot, the viewer is led to identify with a fictional Book of Mormon man who is healed of his blindness by Jesus during his appearance to the ancient Americans.[xxii] After the man is miraculously granted vision, the audience sees the man’s first sight from his perspective: the smiling face of Jesus. In true Hollywood fashion for the emotional climax of a film, the music swells and the film fades to its epilogue.

In Testaments, no expense is spared, and the “full arsenal of visual, aural, and narrative techniques” is unleashed in the service of “evoking the miraculous,”[xxiii] allowing the observer—through the man on-screen—to vicariously experience the Divine through a haze of emotional rapture. Similar to how DeMille worked to present the reality of the life of Christ and the exodus of Israel using what he felt were cinematic proofs, Testaments sought, through the Hollywood and DeMillian practice of filming miraculous moments with spectacular effect, to establish the reality and thorough Christianity of the Book of Mormon.

In Testaments, no expense is spared, and the “full arsenal of visual, aural, and narrative techniques” is unleashed in the service of “evoking the miraculous,”[xxiii] allowing the observer—through the man on-screen—to vicariously experience the Divine through a haze of emotional rapture. Similar to how DeMille worked to present the reality of the life of Christ and the exodus of Israel using what he felt were cinematic proofs, Testaments sought, through the Hollywood and DeMillian practice of filming miraculous moments with spectacular effect, to establish the reality and thorough Christianity of the Book of Mormon.

Having followed the DeMillian protocol for so many decades, the aesthetic expectations of many Latter-day Saints have become entrenched. As Lefler and Burton note,

Mormons, like so many other casual filmgoers, have been conditioned to expect and enjoy the many conventional cinematic elements that mainstream film has accustomed them to. . . . To downplay emotional appeals (or the music that so often cues emotion in the viewer) would seem to many Latter-day Saints to work against achieving a realistic presentation of spiritual moments on screen. This is especially true since Church films have relied heavily upon Hollywood’s emotional techniques, such as mood music, to signal spiritual messages.[xxiv]

Suffice it to say that confidence in the viewer is at a minimum and Latter-day Saint audiences are accustomed to it. They are expected to do little, to be transported nowhere, to simply have spirituality dumped on them through cinematic abundance.

Please continue to Part 2, featuring a discussion of new directions Church-produced media have taken in the decade since The Testaments

[i]Kevin Thomas said of The Ten Commandments (1956), “It is the epitome of the biblical spectacles for which DeMille was so famous.” Robert S. Birchard, Cecil B. DeMille’s Hollywood (Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 2004), ix–x.

[ii]DeMille seemed to love “preaching virtue, while giving audiences a good long look at the wickedness of vice.” Geoffrey Nowell-Smith, ed., Oxford History of World Cinema (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), 34.

[iii] Birchard’s biography of DeMille provides an example from one contemporary reviewer of DeMille’s 1956 production of The Ten Commandments: “While DeMille has broken new ground in terms of size, he has remained conventional with the motion picture as an art form. Emphasis on physical dimension has rendered neither awesome nor profound the story of Moses. The eyes of the onlooker are filled with spectacle.” Quoted in Birchard, DeMille’s Hollywood, 353.

[iv]It would seem, at least in Charles Higham’s view, that DeMille had abandoned “the artistic aspirations which had driven him as a young man. He would simply set out to be a supremely successful filmmaker.” Quoted in Nowell-Smith, World Cinema, 35.

[v]Nowell-Smith, World Cinema, 34.

[vi]Birchard, DeMille’s Hollywood, ix. In addition, Charles Higham observes that even films directed by DeMille that were on more “pagan” subjects “were morality tales, in disguised form reworkings of the moral fairytales which he had learned at the knee of his father, the lay minister and playwright Henry DeMille.” Charles Higham, Cecil B. DeMille (New York: Scribner, 1973), x.

[vii]Thomas notes, “It was [DeMille’s] natural flair for screen storytelling and his patent sincerity that make his films so endearingly entertaining and their messages, in some instances, valid even still.” He also notes that “it is important to see [DeMille’s] work and those of his contemporaries . . . as expressions of a Victorian sensibility committed to uplift as much as entertainment.” Birchard, DeMille’s Hollywood, x.

[viii]Charles Higham notes that DeMille sought to make “the Scriptures attractive and fascinating to the masses in an age of increasing materialism and heathenism. A deeply committed Episcopalian, he literally accepted every word of the Bible without question, and went on record as saying that every word of it with the exception of the Book of Numbers could be filmed exactly as it stood.” Higham, DeMille, x. DeMille distributed copies of the Bible to every member of the cast and crew, inviting them to study the book of Exodus. Furthermore, he hired teams of historians to hunt down the facts available about Moses and required his screenwriters to adhere to those facts religiously while still allowing ample room for enlivening interpolations. Additionally, notes Higham, “DeMille instructed the cameraman Peverell Marley to study hundreds of biblical paintings, examining precisely with what effects of light the old masters achieved their work. Two hundred and ninety-eight paintings were fully reproduced in the film.” Higham, DeMille, 161.

[ix]Birchard, DeMille’s Hollywood, 364.

[x]Paul Schrader, Transcendental Style in Film (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1972), 163.

[xi]Jeffrey Pence notes that DeMille was in favor of using “the moviemaker’s full arsenal of visual, aural, and narrative techniques into the service of evoking the miraculous.” Jeffrey Pence, “Cinema of the Sublime,” Poetics Today 25, no. 1 (Spring 2004): 47.

[xii]Paul Schrader notes that film is “‘an ideal medium for making fantasy seem real,’ the course of action for the religious propagandist was clear: he would simply put the spiritual on film. The film is ‘real,’ the spiritual is ‘on’ film, ergo: the spiritual is real. Thus we have an entire history of cinematic magic: the blind are made to see, the lame to walk, the deaf to hear, all on camera.” For the quoted portion at the beginning of the statement, Schrader cites Durgnat. Schrader, Transcendental Style in Film, 162–63.

[xiii]Schrader is “best known today for his screenplays of arguably redemptive Martin Scorsese films like Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, and The Last Temptation of Christ.” Randy Astle, “Review of Angie,” BYU Studies 46, no. 2 (2007): 325.

[xiv]Schrader, Transcendental Style in Film, 162.

[xv]Schrader observes: “Lazarus plods from his cave, the music soars; why is there no spiritual belief? The truth is, of course, that these films do induce a belief. . . . But this belief cannot honestly be ascribed to the Wholly Other; it is more accurately an affirmative response to a congenial combination of cinematic corporeality and ‘holy’ feelings. And for the many who require no more from sacred art than an emotional experience, these films are sufficient.” Schrader, Transcendental Style in Film, 163–64.

[xvi]Schrader conceded, however, that some sparsely used cinematic magic might be needed to “sustain the viewer’s . . . interest,” while sudden austerity would “meanwhile, elevate his soul.” It was that cinematic asceticism that Schrader viewed as “the proper means of the spirit” (154–155). For Schrader, “the transcendent is beyond normal sense experience” (5), and to attempt to depict it would, by nature, frustrate the goal. Schrader, Transcendental Style in Film.

[xvii]See Thomas J. Lefler and Gideon O. Burton, “Toward a Mormon Cinematic Aesthetic: Film Styles in Legacy,” BYU Studies 46, no. 2 (2007): 292. Schrader felt the film should “deepen our attentiveness to a suggested depth of experience rather than distracting us by [spectacle].” Schrader, Transcendental Style in Film, 164.

[xviii]Randy Astle and Gideon O. Burton, “A History of Mormon Cinema,” BYU Studies 46, no. 2 (2007): 144.

[xix]Notable among them is Wetzel O. “Judge” Whitaker, who many credit for taking “Mormon film from its pioneer infancy into classical maturity.” Whitaker, who had worked at Walt Disney Studios as an animator, producer, and director for nearly two decades, borrowed liberally from the Hollywood system. He instituted a studio-based infrastructure, a move that allowed a consistent style and a high volume of production, allowing the films he produced to have a permeating influence on Latter-day Saint culture. Windows of Heaven (1963), Man’s Search for Happiness (1964), and Johnny Lingo (1969) were some of the more notable productions during Judge Whitaker’s tenure at the head of the Church’s Motion Picture Studio. Though many major LDS productions postdate Whitaker’s retirement, Whitaker’s influence on the system that created these films is notable. Astle and Burton, “History of Mormon Cinema,” 77–95.

[xx]Astle and Burton, “History of Mormon Cinema,” 109.

[xxi]Burton, in a conversation with the author on April 2, 2013, remarked that “Cecil B. DeMille probably visited [Testaments director Kieth Merrill] in the night and said, ‘Great job!’” Enormous sets and lavish costumes were created to convincingly portray the ancient American setting for Testaments—even new words, implied as colloquialisms, were peppered into the dialogue to establish an authentic feel for a forgotten culture. Didacticism was thoroughly present, particularly in a subplot involving a wealthy, villainous straw man who works to persuade one of the film’s central protagonists to leave his family’s faith and indulge in a lifestyle of bold-faced hedonism. A thick plot filled with assassinations and courtroom sequences allowed theatricality to run high and technological sophistication was apparent in a gargantuan earthquake scene where an entire city collapses into chaos and ruin. Sexual titillation was nearly absent in Testaments, though there were the beginnings of a bath scene—something for which DeMille had been famous—a plot beat that leads to a romance between two of the main characters. Testaments even cinematically reproduces paintings by Danish artist Carl Bloch, much as DeMille had done in his films.

[xxii]A tangential similarity between DeMille’s King of Kings (1927) and Testaments is who was cast as Jesus. Higham notes: “As Jesus, DeMille cast the gentle and fragile H. B. Warner, whom he had produced in The Ghost Breakers some twelve years earlier.” Higham, DeMille, 166. “Gentle and fragile” could arguably be used to describe Danish actor Tomas Kofod in the role of Jesus in Testaments (Will Swenson’s voice was dubbed over Kofod’s because of Kofod’s strong Danish accent).

[xxii]A tangential similarity between DeMille’s King of Kings (1927) and Testaments is who was cast as Jesus. Higham notes: “As Jesus, DeMille cast the gentle and fragile H. B. Warner, whom he had produced in The Ghost Breakers some twelve years earlier.” Higham, DeMille, 166. “Gentle and fragile” could arguably be used to describe Danish actor Tomas Kofod in the role of Jesus in Testaments (Will Swenson’s voice was dubbed over Kofod’s because of Kofod’s strong Danish accent).

[xxiii]Pence, “Cinema of the Sublime,” 47

[xxiv]Lefler and Burton, “Film Styles in Legacy,” 289

Thanks! Do you have any indication on how much the aesthetic decisions made when making Testaments was director Kieth Merrill’s decisions, and how much it was decided by higher-ups? Also, with Testaments, there it is clear who made the film, it was part of the roll-out. It seems like it is less obvious with more recent Church-produced films. Was it important for your research to know exactly who was behind the making of the films?

I was looking in Wikipedia for Emma Lou Thayne. They have very little on Mrs. Thayne. I ask that you allow me to share your information with Wikipedia, citing you as the source of the information. If not this, you may consider sharing your information with Wikipedia.

Sincerely,

Bart McRae

Sure, you have permission to use the Emma Lou Thayne In Memoiram piece to edit a page on Wikipedia, as well as any other of the articles here.