Guest post by Katherine Cowley

Sometimes in Mormon literature—and in church lessons—we focus on grand moments and events, things like baptism, a mission, or a temple marriage. These become the ultimate goal for ourselves and others. If we gain a testimony, find the right person to spend our lives with, and make covenants, then we can live our “happily ever after.”

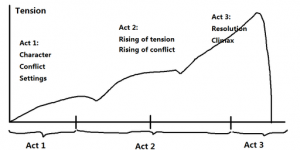

In terms of three act plot structure, the mission or the marriage or another grand event is the climax of the story. Everything after that is falling action: it’s the denouement, the wrapping up of loose ends, but most of the important decisions have been made, most of the important actions have been taken, and we’re past the crucial struggle.

But what happens if one of these grand moments does not occur? What if someone doesn’t serve a mission or comes home early? What if someone doesn’t marry, or does, but their spouse is abusive? Or what if everything goes stereotypically right but then the real struggles of faith and family and life come later?

In terms of plot structure, what I’m proposing is that we need stories where these grand moments are not the climax of the story, but rather the inciting incident.

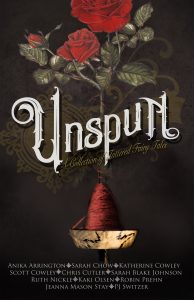

I am one of editors-in-chief for a new anthology, Unspun: A Collection of Tattered Fairy Tales, released April 10, 2018. While the book does not have LDS content, most of the authors are LDS. The core question of the book is what happens after the classic end of fairy tales. Each poem, short story, or novella focus on the struggles and stories that occur after the line, “and they all lived happily ever after.”

To give a few examples of how the grand moment becomes the inciting incident, in “Breadcrumbs” (by the 2017 Mormon Lit Blitz winner, Jeanna Mason Stay), Gretel defeated the witch in the gingerbread house years before the start of the story. But now she must deal with post-traumatic stress disorder.

To give a few examples of how the grand moment becomes the inciting incident, in “Breadcrumbs” (by the 2017 Mormon Lit Blitz winner, Jeanna Mason Stay), Gretel defeated the witch in the gingerbread house years before the start of the story. But now she must deal with post-traumatic stress disorder.

“Rumpelstiltskin’s Daughter,” by Ruth Nickle, explores how the agency of others can create decades-long struggles and trials in someone’s life. In “Tsar Vislav, Tsarina Vislav, and the Firebird,” a mother must clean up the consequences of her adult son’s quest.

My story is a novella titled “Tatterhood and the Prince’s Hand.” In the original fairy tale, after an arduous quest to save her sister, Tatterhood receives the ultimate prize: a wedding to a foreign prince. My story occurs six months later. Tatterhood is pregnant, and also not very happy with her husband, Trygve. After their marriage, they have discovered how very different they are, and Tatterhood suspects that Trygve finds other women more desirable than her. When Trygve is captured by a magical creature, Tatterhood isn’t certain whether or not she wants to rescue him.

Ultimately, it’s a story about love and forgiveness and loyalty. As I wrote, I tried to deal with the struggles of marriage. While some marriages are smooth-sailing for decades, most have bumps and challenges. What do you do when you have drifted apart, when you disagree about crucial issues, or when you discover your spouse has a pornography addiction? All of these are real, challenging issues, and we need stories, both realistic and fantastical, that provide a template for these “after ever after” journeys.

Some of my favorite literature by Mormons feature their own “after ever after” journeys. In Brandon Sanderson’s Alloy of Law series, the main character’s wife is killed in the prologue of the first novel. It takes him multiple books to deal with her loss, and some of the pain and struggle continues even once he moves forward. Some characters try to fix his problems, others try to find someone who could replace his wife, but ultimately, the person who helps him the most is the one who just spends time with him and allows him to mourn.

Some of my favorite literature by Mormons feature their own “after ever after” journeys. In Brandon Sanderson’s Alloy of Law series, the main character’s wife is killed in the prologue of the first novel. It takes him multiple books to deal with her loss, and some of the pain and struggle continues even once he moves forward. Some characters try to fix his problems, others try to find someone who could replace his wife, but ultimately, the person who helps him the most is the one who just spends time with him and allows him to mourn.

Messages on the Water, a poetry collection by Merrijane Rice, also deals with these “after ever afters.” The poems that speak to me most  address the continuing struggles we face in our lives. In “On Trial,” fear threatens to overtake faith, as “My optimism vacillates like tides/ progressing bit by bit, then falling back.” In “Sister,” we never find out what happened to the narrator’s sister, but, in second person, we read of how she “swallows sorrow like knives” and of the narrator’s gradual attempts to ease some of the burden.

address the continuing struggles we face in our lives. In “On Trial,” fear threatens to overtake faith, as “My optimism vacillates like tides/ progressing bit by bit, then falling back.” In “Sister,” we never find out what happened to the narrator’s sister, but, in second person, we read of how she “swallows sorrow like knives” and of the narrator’s gradual attempts to ease some of the burden.

Ultimately, what happens after the grand moments—baptism, the mission, the temple—is the bigger part of our lives. Enduring to the end is an active process, full of struggle. The rod is long and the mists are plenty. And it can be harder to press forward if we assumed our trials were over, if we thought we had already reached the point of “happily ever after.”

In LDS theology, the goal is happiness, and that is something we should seek to have—and can experience—throughout our lives. Yet it can be argued that “happily ever after” is not meant to arrive in this life: “happily ever after” is exaltation, a gift that we receive only after a life-long journey.

We still need Mormon literature where these grand, joyous moments occur as the climax of the story. But we also need stories where these moments are the inciting incident or the midpoint, because we need stories we can carry with us throughout all the moments of our stories.

Katherine Cowley is the author of the novelette “The Clockwork Seer,” which is part of the steampunk anthology Steel and Bone. She has been telling stories since she was five years old, when she retold the Icarus myth in the form of a picture book, The Turtle That Got Too Close To The Sun. Her short publications have won awards in the Mormon Lit Blitz, Four Centuries of Mormon Stories, the Meeting of the Myths contest, Segullah, the BYU Studies Personal Essay contest, and the Tempe Community Writing Contest.