Here is a short lyric by H.D. Compare it to the lyric by Wallace Stevens that follows it.

Reed,

slashed and torn

but doubly rich—

such great heads as yours

drift upon temple-steps,

but you are shattered

in the wind.

Myrtle-bark

is flecked from you,

scales are dashed

from your stem,

sand cuts your petal,

furrows it with hard edge,

like flint

on a bright stone.

Yet though the whole wind

slash at your bark,

you are lifted up,

aye—though it hiss

to cover you with froth.[i]

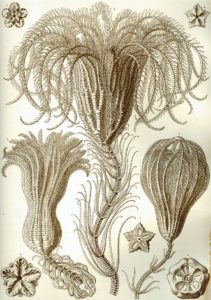

HD wants you to see that sea lily. This animal[ii], looking damaged by wind, frayed by sand carried in the tide, by the wash of the waves, this sea lily is the poem. It is not the subject of the poem. What HD wants you to see is the sea lily, through its likeness to a reed knocked down.

And here is a short lyric by Wallace Stevens. From its title, you might think Stevens wants the same thing as HD:

NOT IDEAS ABOUT THE THING

BUT THE THING ITSELF[iii]

At the earliest ending of winter,

In March, a scrawny cry from outside

Seemed like a sound in his mind.

He knew that he heard it,

A bird’s cry, at daylight or before,

In the early March wind.

The sun was rising at six,

No longer a battered panache above snow . . .

It would have been outside.

It was not from the vast ventriloquism

Of sleep’s faded papier-mâché . . .

The sun was coming from outside.

That scrawny cry—it was

A chorister whose c preceded the choir.

It was part of the colossal sun,

Surrounded by its choral rings,

Still far away. It was like

A new knowledge of reality.[iv]

This is the last poem in The collected poems of Wallace Stevens. That does not tell us anything about when it was written. It’s hard to tell with Stevens. But I remember one of my teachers at the University of Washington, I believe it was Richard Blessing, remarking that Stevens wanted to call his collected poems The whole of Harmonium, since the first collection of his poems, published in 1923 by Knopf, was called Harmonium. Stevens considered his work to be a whole, and the “Note on the Text” that follows this poem indicates how picky he was about the printed texts of all the poems, and spelling, and punctuation. The editors of “The corrected edition” indicate how far they had to go to provide the corrections to this collection. And how much help they needed from librarians to get the correct texts before 1983, when this collection was copyrighted.

So I don’t know when this poem was written, let alone first published, whereas “Sea Lily” was published in 1916, in HD’s first collection, Sea garden. The titles of the two first collections are instructive of the difference between the poets and their approaches to writing. A “harmonium” is a reed organ, an instrument that requires a player — indeed, a skilled player. A “sea garden” is a koan, especially when first published: a puzzle presented to the reader. “I made this” it says to the reader; “what do you make of it?”

So I don’t know when this poem was written, let alone first published, whereas “Sea Lily” was published in 1916, in HD’s first collection, Sea garden. The titles of the two first collections are instructive of the difference between the poets and their approaches to writing. A “harmonium” is a reed organ, an instrument that requires a player — indeed, a skilled player. A “sea garden” is a koan, especially when first published: a puzzle presented to the reader. “I made this” it says to the reader; “what do you make of it?”

HD is the skilled observer, using the metaphor of a reed to begin exploring an animal perhaps as odd as a sea garden. But she presents her observation, scrupulous as it is, seemingly without commentary. The observation “such great heads as yours / drift upon temple steps” places the sea lily in a context where it could be worshipped for its beauty, or enhance the beauty of a place of worship — but Doolittle immediately undercuts this imagery by returning to its context, the sea shore, and its life with the tide, “lifted up” even against “the whole wind … though it hiss / to cover you with froth.” This sea lily, she insists, will be seen.

In contrast to this careful imagery, Stevens insists on being central to his poem “Not Ideas About The Thing But The Thing Itself” — or at least insists on a persona playing on the organ of his observation. The “scrawny cry” is an elegant characterisation of an early-morning bird call, but in the second stanza Stevens insists that “He knew that he heard it,” this persona. Doolittle keeps her observer apart from the observed. But Stevens’ observer is central to the thing itself: at first, “a scrawny cry from outside / Seemed like a sound in his mind.” It has a dual character, this sound: the observer knows he heard it, but it seems something otherwise. By the time the poem finishes, the observer has it pegged, in the metaphor of the chorister — surely an idea about the sound. I wonder whether his title for the poem is ironic.

It is not that HD could not write poems in a persona. In fact, to me, she seems to always write in personae. They are sometimes impenetrable to me, like the observer of the Sea Lily above, or the speaker of this next poem:

The Gift

Instead of pearls—a wrought clasp—

a bracelet—will you accept this?

You know the script—

you will start, wonder:

what is left, what phrase

after last night? This:

The world is yet unspoiled for you,

you wait, expectant—

you are like the children

who haunt your own steps

for chance bits—a comb

that may have slipped,

a gold tassel, unravelled,

plucked from your scarf,

twirled by your slight fingers

into the street—

a flower dropped.

Do not think me unaware,

I who have snatched at you

as the street-child clutched

at the seed-pearls you spilt

that hot day

when your necklace snapped.

Do not dream that I speak

as one defrauded of delight,

sick, shaken by each heart-beat

or paralyzed, stretched at length,

who gasps:

these ripe pears

are bitter to the taste,

this spiced wine, poison, corrupt.

I cannot walk—

who would walk?

Life is a scavenger’s pit—I escape—

I only, rejecting it,

lying here on this couch.

Your garden sloped to the beach,

myrtle overran the paths,

honey and amber flecked each leaf,

the citron-lily head—

one among many—

weighed there, over-sweet.

The myrrh-hyacinth

spread across low slopes,

violets streaked black ridges

through the grass.

The house, too, was like this,

over painted, over lovely—

the world is like this.

Sleepless nights,

I remember the initiates,

their gesture, their calm glance.

I have heard how in rapt thought,

in vision, they speak

with another race,

more beautiful, more intense than this.

I could laugh—

more beautiful, more intense?

Perhaps that other life

is contrast always to this.

I reason:

I have lived as they

in their inmost rites—

they endure the tense nerves

through the moment of ritual.

I endure from moment to moment—

days pass all alike,

tortured, intense.

This I forgot last night:

you must not be blamed,

it is not your fault;

as a child, a flower—any flower

tore my breast—

meadow-chicory, a common grass-tip,

a leaf shadow, a flower tint

unexpected on a winter-branch.

I reason:

another life holds what this lacks,

a sea, unmoving, quiet—

not forcing our strength

to rise to it, beat on beat—

a stretch of sand,

no garden beyond, strangling

with its myrrh-lilies—

a hill, not set with black violets

but stones, stones, bare rocks,

dwarf-trees, twisted, no beauty

to distract—to crowd

madness upon madness.

Only a still place

and perhaps some outer horror

some hideousness to stamp beauty,

a mark—no changing it now—

on our hearts.

I send no string of pearls,

no bracelet—accept this.[v]

This is not a long poem for Doolittle, especially early Doolittle. Poets.org dates it to 1916, and in Collected poems 1912-1944 it follows “Sea Lily” after one other poem. To me, it offers such a startling contrast that I present it as evidence that she was never merely an Imagiste. The complexity of the emotion here matches anything in Dickinson, whose fractured syntax she echoes. I don’t know whether she knew of Dickinson’s work this early in her own career, and she uses a looser-jointed line, but she is in some ways nearly as impenetrable as Dickinson.

Wallace Stevens seems to have written most of his long poems early on, and published them in Harmonium; in Doolittle’s corpus, the later poems are the longer ones, like the three published in 1944-1946: The Walls Do Not Fall, Tribute To The Angels and The Flowering Of The Rod (later published together as Trilogy). Of the latter, Louis L. Martz says, in his introduction, that “the poet here creates a new myth of redemption”[vi] — speaking specifically of The Flowering Of The Rod, but in general of the entire Trilogy. In this regard, HD seems to have followed once again the trail pioneered by Ezra Pound, this time emulating his Cantos, but in her own way.

But hold on, I hear you say: Pound? Did she follow him into madness, too?

Your turn.

[i] Collected poems. 1912-1944 / H.D. / edited by Louis L. Martz. — New York : New Directions, 1983, p. 14.

[ii] As far as I can tell, she is writing about a crinoid, a member of the echinodermata phylum, according to https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crinoid.

[iii] This SCREAM is a necessary representation, following Knopf’s practice, and perhaps Stevens’s, of writing his titles in capital letters. Maybe I am too used to the web practice of INDICATING YELLING BY CAPITAL LETTERS. Perhaps there is some allusion to Roman inscriptions buried in the practice, but I doubt it. It appears to be yet another convention of poetry publishers, and/or poets, like starting each line with a capital letter, that has dropped out of use.

[iv] The collected poems of Wallace Stevens. — Corrected ed. / edited by John N. Serio and Chris Beyers. — New York : Vintage, 2015; pp. 565-566.

[v] HD, op. cit. pp. 15-18.

[vi] Op. cit., p. xxxv.

All illustrations cribbed from Wikipedia, with the following credits:

The drawing of the sea lily is from Ernst Haeckel.

The Crinoid vrae is from the NOAA Photo library – https://www.flickr.com/photos/noaaphotolib/9717633143/in/set-72157635438729212

The photo of the harmonium by Boygold – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=22232571

Featured photo by Nichole Thrasher