Guest post by Ryan Shoemaker

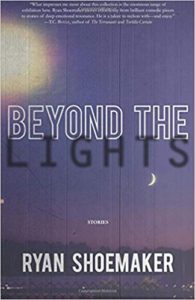

As a writer who attempts to keep one foot firmly planted in the world of Mormon letters, I’m happy to announce the publication of my debut story collection Beyond the Lights.

As a writer who attempts to keep one foot firmly planted in the world of Mormon letters, I’m happy to announce the publication of my debut story collection Beyond the Lights.

Soon after No Record Press accepted the manuscript for publication, a friend, who’d already read a few of the stories, asked: “Well, what’s the collection about?” While I could speak about each story, discussing and illuminating aspects of character, plot, point of view, and setting, I sensed my friend was getting at a deeper question, one that transcended each individual story. He was asking about a unifying theme, a common thread woven through the collection.

Certainly, this common thread is more overt in short story cycles like Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohioand Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried, collections in which the stories, while able to stand alone, are often bound together by character, geography, and theme, thus creating a more profound reading experience as a whole than as parts. The stories in my collection, at least in my mind, were separate entities, disparate bedfellows who happened to find themselves shoulder to shoulder between a book cover. But my friend’s question intrigued me. Could these stories, moving through rural, urban, and suburban landscapes, and written over more than a decade as I moved from a young newlywed to a young father, from a graduate student to an inner-city high school teacher, and then back to a graduate student—could these stories, if atomized and examined closely, reveal a common thematic thread or preoccupation? Maybe.

Perhaps if there’s a unifying theme, it might be one that explores illusion in a few of its pernicious varieties: those illusions about the paralyzing, self-defeating narratives that cause us to fixate on the disparity between the lives we want to live and the reality of the lives we live; illusions about the self-aggrandizing, self-righteous narratives all of us, from time to time, construct for ourselves, the kind that build up a false hierarchy of righteousness from which we look down on others; and, finally, illusions about the narratives we construct for others, either to justify our vilification or to salve a guilty conscience.

Beyond the Lights, then, is populated by a cast of characters beset by illusion: the Phoenix architect who constructs a romantic backstory for the two undocumented workers he hires on the cheap to clean his office; the self-righteous Mormon high school guidance counselor who, in his private mind, feels morally and spiritually superior to his friends, yet soon realizes how his conceit has cut him off from true human connection; and two high school boys who idolize their charismatic friend, only to see him eventually for the charlatan he is.

The inherent dilemma, I’ve found, in writing about characters hamstrung by crippling illusion is that they tend to be unpleasant individuals, a sharp deviation from the facile axiom of writing that protagonists should be, in the final analysis, likeable or sympathetic. In this debate, I tend to lean toward American writer Claire Messud’s recommendation to her readers that, “If you’re reading to find friends, you’re in deep trouble.” Perhaps literature, then, shouldn’t require likability of characters, but rather foster an understanding and connection to them that go beyond the surface to see profoundly, and even spiritually, the whole of a person with all of her or his flaws and brokenness. To even love this imperfect person. If anything, many of my characters—“wrestling with blind spots,” as Aimee Bender rightly notes of them—while not always changing for the better, at least come to recognize, even vaguely, the illusions that impede them, a necessary first step toward change.

But the mischief in me wants to dismiss as foolish this whole debate about likability and unlikability—as if we offend our characters by assigning them to one category or the other. Because who are they, all these characters? Nothing more than vivid artifice, clothed, provided a compelling script, and steered by the writer’s imagination through conflict. My allegiance isn’t to my characters—it’s to my readers, and maybe, just maybe, they’ll avoid some of my characters’ mistakes.

Ryan Shoemaker’s fiction has appeared in McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, Gulf Stream, Santa Monica Review, Booth, Juked, and Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon, among others. His debut story collection, Beyond the Lights, a semifinalist for the St. Lawrence Book Award, is available through No Record Press or at Amazon. T.C. Boyle called it a collection that “moves effortlessly from brilliant comedic pieces to stories of deep emotional resonance.”