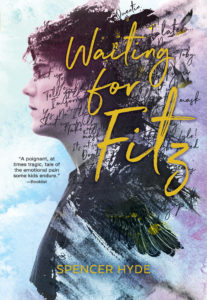

Spencer Hyde is introducing Waiting for Fitz, his debut novel, about two young people suffering from mental illnesses, which is being published by Shadow Mountain next week. Hyde was the winner of the 2015 AML Short Fiction Award for his story “Remainder”. He has recently joined the Brigham Young University English Department faculty.

Spencer Hyde is introducing Waiting for Fitz, his debut novel, about two young people suffering from mental illnesses, which is being published by Shadow Mountain next week. Hyde was the winner of the 2015 AML Short Fiction Award for his story “Remainder”. He has recently joined the Brigham Young University English Department faculty.

How did this story come about?

It’s hard to pinpoint a genesis for the story of Waiting for Fitz because it feels like it has been a part of me for so long. When studying in college, I read a lot of Tom Stoppard and was entranced by the way he addressed weighty issues while maintaining a witty, comedic mode. I’ve strived to maintain that balance ever since (and I’ve always had a penchant for the absurd).

I remember being totally floored after my first reading of The Importance of Being Earnest when I saw Oscar Wilde hit a perfect note one line after another. I remember the moment I first encountered the prosody of Frost and the metre of Tennyson. I often draw inspiration from the movement of poetry. Look at, for example, the first lines of “The Splendor Falls” and you’ll see what I’m talking about. I began from that moment with “Whitewashed walls and medical halls, and memory as told in story,” mimicking his poetic rhythm, and immediately I was in the psych ward and building a world from those words.

In that sense, I started writing this books years ago, though I didn’t know it at the time. I wondered at the origins of character and their background and motivation after reading Samuel Beckett’s plays and Flannery O’Connor’s short stories. I started thinking of how to rearrange a universe after reading Hamlet followed by Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead. I considered the importance of the first sentence after reading Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude. My understanding of a work’s final moment was forever altered when I encountered the final paragraph of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road. My focus on dialogue was shaped by playwrights like Sarah Ruhl and novelists like Ali Smith, and I was greatly schooled in characterization by the likes of Annie Proulx.

The story first opened up when Addie’s voice came to me, and I thought of what it might be like to narrate from a female perspective. And it’s not hyperbole to say that her voice came to me—one line ran through my mind and I spent the next many months chasing that personality. I was sitting in bed and had my phone next to me (ideas often hit me late at night, and I always take notes on my phone), and I heard one line: “It’s not that you need to hear it or anything—just that I need to say it.” I often start stories with voice and build everything else around that entity, and this line gave me an ember of Addie’s character. Then, I set the billows to work on that ember.

But all of this, all my writing, is done because I believe fiction has a way of reminding us what it means to be human, and that things don’t always turn out like we’d expect. And that’s a good thing. Perhaps if I’d encountered the right book at an earlier age I would be able to grapple with OCD and anxiety and depression a bit better—maybe I’d be better prepared for what came next.

Fiction allows us an opportunity to practice empathy. Fiction reminds us what it is to be human. And I can say without hesitation that without fiction, without essays, without poems, without plays (and yes, a lot of other “drama”), I could not have overcome my OCD to the degree I have. I wrote this novel to open up the conversation about mental health through practicing that empathy, and I hope it resonates with every reader. I heard one author call all stories “hope machines,” and I think that’s spot on. I hope you enjoy my own little hope machine in Waiting for Fitz.

Synopsis

Addie loves nothing more than curling up on the couch with her dog, Duck, and watching The Great British Baking Show with her mom. It’s one of the few things that can help her relax when her OCD kicks into overdrive. She counts everything. All the time. She can’t stop. Rituals and rhythms. It’s exhausting.

When Fitz was diagnosed with schizophrenia, he named the voices in his head after famous country singers. The adolescent psychiatric ward at Seattle Regional Hospital isn’t exactly the ideal place to meet your best friend, but when Addie meets Fitz, they immediately connect over their shared love of words, appreciate each other’s quick wit, and wish they could both make more sense of their lives.

Fitz is haunted by the voices in his head and often doesn’t know what is real. But he feels if he can convince Addie to help him escape the psych ward and get to San Juan Island, everything will be okay. If not, he risks falling into a downward spiral that may keep him in the hospital indefinitely.

Waiting for Fitz is a story about life and love, forgiveness and courage, and learning what is truly worth waiting for.

Waiting for Fitz Excerpt

My life took off the comedy mask and put on the tragedy mask at the end of my seventeenth year. I won’t get all sentimental about it, but you need to hear the whole story to make sense of that mask swap or whatever.

So my mom thought I needed more help than I was getting from my regular psychologist, Dr. Wall. I remember him getting upset once when I jokingly told him I felt like I had my back up against him at times. I started seeing him after my rituals got real bad. Like, really messy. He was less than motivational, to put it kindly. But I’d started showering about four times a day and washing my hands over a hundred times a day because my mind was telling me the people I loved would die if I didn’t. That sounds absurd, right? Don’t I know it. But in the moment it was life or death. Seriously.

If you look up “obsessive compulsive disorder” you’ll probably run into some really obnoxious stuff that isn’t all that accurate. Or, if it is accurate, it’s made to sound like it’s something that just takes care of itself or that gets resolved by some loving therapists, followed by some block party thrown in your honor. It’s not all Hallmark-channel type stuff. Trust me.

Let’s be honest: We all have issues. Let’s be even more honest: Sometimes we need help but don’t want to face it. I understand now why my mother was looking for more help, for better help, but at the time I thought she was just overreacting. I mean, don’t most teenagers have a three-hour morning ritual before they can walk out the door? Don’t most teenagers wash their hands to keep their families alive? Just kidding. A little. But that’s how it went with OCD. I guess if we get super technical, it’s not all that untrue. But I did need help, and Mom took action.

She took me to see this nationally renowned doctor the summer before my senior year of high school. Apparently it was the only time in the last decade that this particular doctor had worked the floor of the psychiatric ward at Seattle Regional Hospital. But it also meant that I was to be an inpatient.

So, before you get all excited about this kind of added support, know that it meant I had to postpone my senior year of high school and stay in a psychiatric ward—the nuthouse, the puzzle box, the cuckoo’s nest. Whatever. Look, Seattle is far from being a bad place to live, but if you are only able to see the world from six stories up it’s just like any other place.

Here’s how my first day went: I started the day by talking with Dr. Riddle—yes, that was his name, get over it—about the severity of my OCD. I wasn’t hiding the fact that I needed help, but I also wasn’t going to admit that staying in a hospital was the best thing for me. I mean, I was trying to focus on important things like The Great British Baking Show. Have you ever wondered what it would be like to sample that stuff? What do they do with it all after they bake it? What a waste.

I made a killer baklava, and I was going to miss, like, an entire season at the very least. I made Mom record every episode and promise she wouldn’t watch them without me. The last time we watched had been a few weeks before I entered the hospital. I remember Mom walking over to the couch and crowding my space a little. She sat on my feet and warmed them up.

“Richard forgot the bread portion of the presentation this time, and he forgot to preheat the oven,” she said, spoiling it. I wasn’t there yet. Two minutes later, Richard indeed made both those mistakes.

My mom was a bit of an amateur baker herself, though she never let things prove for long enough; she was too impatient. I had proof.

“Look at that,” I said. “Richard lacks toast, and he’s still tolerant. More than I can say for you.”

“What? I’m tolerant. Except for lactose.”

“You don’t lack toast. You had some for breakfast. I saw it. But sometimes you’re still intolerant,” I said. “Maybe you’re also gluten-intolerant. Maybe you’re also flour-intolerant.”

“This is why nobody can watch shows with you, Addie,” she said.

“You’re a flour-ist!”

“A florist?”

“No, but I’d love to see a florist who only sold flours. Tapioca. Potato. Spelt. Buckwheat,” I said.

“You’re obnoxious,” Mom said, smiling.

“Also, you can’t preheat an oven. It’s not possible. Anything is technically preheated. What you do is heat the oven,” I said. “It’s like how we say an alarm goes off. Well, that would mean it was on to begin with. We’d be relieved to have an alarm go off, so it would stop sounding, you know?”

“Like I said—obnoxious,” she said.

I was so sick of Richard being named Star Baker over Martha just because he had better presentations. It only matters how it tastes! Martha was the baker with the right flavors, and I thought that should win out over looks. Frankly, that should win out over anything.

I was there in the ward after Mom had explained why I needed the extra time in the hospital or whatever, so I wasn’t too shocked by her leaving, though the fact that I was alone really hit me later on.

“This is about you, Addie,” she said.

I alternately blinked each eye because I was counting to the number seven each time I heard my name. I’d been starting to think of the disorder as a paradox. Zeno, the School of Names—they both had the same idea, which was this: “A one-foot stick, every day take away half of it, in myriad ages it will not be exhausted.” That’s how I felt. Like I could walk halfway to the end of the room but never make it to the wall. Not really. Because I’d only ever be able to go halfway. I felt that even with all of my rituals, I’d never really make it to the end. It’d be impossible. At times, I felt impossible. Zeno had it right—an infinite number of rituals, and I’d still never arrive.

“I’m just winking at you, Mom. You know that.”

She smiled and hugged me and started crying. Like, big and wet and messy kind of crying. I won’t lie and say I didn’t feel it, but with all the doctors milling around, I tried to be strong, and I thought not crying was mature. Looking back, I know I was wrong and I should’ve just let it happen.

I know a lot of things now, but at the time I was so consumed by my own disorder. It might look like my stay at the hospital was just a stopover for some new meds, or for added doctoral support. But it wasn’t. I needed serious help, and I didn’t want to admit it.

Each morning before school, I’d walk to the bathroom, careful not to brush the wrong thread when I reached the threshold. I’d stand up and sit down three times before entering the bathroom. I’d sniff two times with each step while also counting the tiles beneath each foot. I’d make sure I blinked with my left eye before entering the shower. Counting each tap on the shower wall, each tap on the faucet, and each throat-clearing, I’d net two hundred and seven. I’d do this seven times before exiting the shower. Then I’d wash my hands forty-three times. Those two numbers added together made two hundred and fifty, and the two and the five made seven, of course—my favorite number. Finally, I’d dry off, sit on the bed, and count to eleven. What a great number, eleven: it’s first place two times, or seven and four, which is nice.

If anything went wrong at all during the ritual, I’d have to leave the bathroom and start over with a new towel, the carpet fibers back in the right place, the right amount of blinks per step, the right motion for each scrub, the right thoughts for the entirety of my time in the shower. If I pictured Mom’s face and thought of the words death or cancer or tragedy, I would have to turn the water off and start over.

Again. Again. Again. The dichotomy paradox in action. I was a living paradox.

My downward spiral was similar to that water, getting sucked down and down until the rabbit hole was no longer a myth, and I was stuck in some alternate reality wishing there was a potion I could drink to get me out of there.

But I had to hope. That’s all I had left between my bleeding hands and crushing thoughts.

My rituals weren’t just confined to the bathroom. They followed me everywhere. I’d have to flip the lights on and off seventeen times before stepping on the stairs. I’d count each step, blinking three times with each left-foot step, four with each right-foot step—all the while, thoughts of death circled in my head. If I didn’t tap the stair banister in the right increments, three times each, I was convinced that cancer would eat my mother from the inside out, turning her bones into dust.

She’d watch me with large, sad, hopeless eyes as I’d back up the stairs and start over. Each number I counted was tied to the safety of my mother, of my dog, of anybody or anything close to me. One misstep, one ritual imperfectly observed, and I had to start over so my mom wouldn’t get in a car wreck on her way to work, so the dog wouldn’t get tumors in her legs and slowly crumple to the floor. Stupid, I know. But try telling my mind that it wasn’t as real as the thumping machine in my chest, pulsing behind my rib cage.

…

Spencer Hyde spent three years of his high school experience visiting Johns Hopkins for severe OCD. He feels particularly suited to write Waiting for Fitz because he’s lived through his protagonists’ obsessions. Spencer worked at a therapeutic boarding school before earning his MFA at Brigham Young University and his PhD at the University of North Texas, specializing in fiction. He wrote Waiting for Fitz while working as a Teaching Fellow in Denton, Texas. He is currently an assistant professor of English at Brigham Young University. Spencer and his wife, Brittany, are the parents of four children. They love to hike, read, watch movies, fly-fish, and bake.

Spencer Hyde spent three years of his high school experience visiting Johns Hopkins for severe OCD. He feels particularly suited to write Waiting for Fitz because he’s lived through his protagonists’ obsessions. Spencer worked at a therapeutic boarding school before earning his MFA at Brigham Young University and his PhD at the University of North Texas, specializing in fiction. He wrote Waiting for Fitz while working as a Teaching Fellow in Denton, Texas. He is currently an assistant professor of English at Brigham Young University. Spencer and his wife, Brittany, are the parents of four children. They love to hike, read, watch movies, fly-fish, and bake.

See also Spencer’s LDS Living article, “How 2 Bible Stories Shaped My Perspective on Mental Illness.”

.

I really appreciated the personal history of a writer through books. I share a lot of that dna.