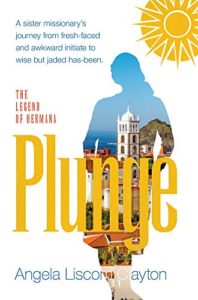

Angela Liscom Clayton is introducing her new memoir, The Legend of Hermana Plunge, about her service in the Canary Islands in 1989-1990. The memoir was published last week by By Common Consent Press.

Angela Liscom Clayton is introducing her new memoir, The Legend of Hermana Plunge, about her service in the Canary Islands in 1989-1990. The memoir was published last week by By Common Consent Press.

I had two inspirations in writing my own mission memoir, The Legend of Hermana Plunge. The first was Craig Harline’s excellent mission memoir Way Below the Angels which I enjoyed reading but couldn’t help feel that there was a real need for such a story to be told by a sister missionary. My second inspiration was Sheryl Sandberg’s second wave feminist leadership book, Lean In. I had been in discussions with a friend about writing something for women in the church, encouraging them to also “lean in” rather than taking a backseat to Priesthood authority. That book’s still just a few scrawled pages of notes and may never get off the ground.

As I felt at the time I was considering a mission:

It seemed to me that too little was expected of women in the Church. You could drop out of school or get a soft degree to avoid taking classes you found challenging, you could choose not to work, you could skip mission service, and it didn’t matter. We weren’t expected to do anything really, other than be attractive enough to get married and procreate. At every turn, the option to do less seemed to be encouraged, and I had too much personal ambition to take the easy way out. If men were expected to serve, why wasn’t I? Was I a lesser Christian disciple? I sure didn’t think so.

There are a few aspects to the book that are unique among mission memoirs. I worked hard to avoid writing an essay, lecturing, or giving advice. Rather than cherry-picking anecdotes to make specific points, I wanted to allow readers to experience a mission first hand, so I kept it chronological and used dialogue and character sketches to bring to life the mission life that I experienced, in all its absurdity and frustration, its petty triumphs and joys.

As a sister, and a perpetual outsider to the mission’s hierarchy, I found that my stories reflect a keen awareness of mission politics. Another dynamic that the book highlights that is forever changed since the age shift of 2012, is the two year age difference sisters from my era had when compared to the elders with whom we served and who were theoretically our leaders. We faced occasional sexism, hypocrisy, gossip, street harassment, and unwanted attention, and we also sometimes received respect, friendship, and true partnership. We sometimes developed leadership skills specifically because we were barred from positions of authority. We were only able to influence others through the merit of our ideas and our persuasiveness.

I also discovered in my reflections that the way sisters interacted with each other was often very different from how the elders worked together. While there were sometimes conflicts or personality clashes, we often developed mutual loyalty in our separation. On the rare occasions when I was in an apartment with another companionship, there was a real sense of joy and fun that it seems was more rare for the elders.

My mission experience was unique in another way that many have found intriguing. Although Spain Las Palmas is in Europe, we were a high-baptizing mission thanks to the controversial use of Alvin Dyer’s Challenging and Testifying Missionary approach. Dyer was also credited with the “baseball baptism” strategy, although this was not specifically employed in our mission. This approach radically altered how missionaries taught and gained commitments from investigators, and also likely contributed to low retention rates and local member burnout. The book presents what it was like to operate under this type of mission culture. And yet, nobody should think they will find the silver bullet to success in the book’s pages.

We weren’t doing anything different than anybody else. It wasn’t magical. It wasn’t in our control. Our fame wasn’t deserved. You could be obedient or not, set high goals or low ones, speak the language well or not, work this area or that one, get along with your companion or hate her guts, but it really depended on finding the people who happened to need you at that time. It was very situational. Things sometimes just clicked.

I had originally expected my memoir to be of greatest interest to women who did not serve a mission, who considered going but didn’t feel strongly enough to go, or who got married before the requisite mission age of twenty-one. I hoped that the memoir would give them a chance to experience it for themselves, to feel more aware of what such an experience was like. I have been pleased to find that the memoir really speaks to men who served who have found it fascinating and insightful to glimpse the aspects, both subtle and obvious, in which mission service differed for their female counterparts. Perhaps at heart it’s a desire to see themselves from a woman’s perspective. I have also heard from many women who served who have found the experiences, stories and emotions to resonate with their own missions.

Angela Liscom Clayton is a retired business executive and current small business owner. She is married with three children and lives in Scottsdale, AZ. In addition to writing and reading, she enjoys traveling, hiking, and oil painting. She has a degree in English Literature. She blogs at Wheat and Tares and By Common Consent.

Angela Liscom Clayton is a retired business executive and current small business owner. She is married with three children and lives in Scottsdale, AZ. In addition to writing and reading, she enjoys traveling, hiking, and oil painting. She has a degree in English Literature. She blogs at Wheat and Tares and By Common Consent.