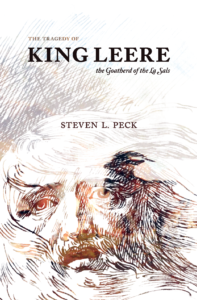

An interview conducted by Steven L. Peck, with the author of the newly released, King Leere, Goatherd of the La Sals (AoKLGotLS)

An interview conducted by Steven L. Peck, with the author of the newly released, King Leere, Goatherd of the La Sals (AoKLGotLS)

Steve: Before we get to the book tell us about yourself. This is your fifth novel if I’m not mistaken. In addition, you’ve published two collections of short stories, a collection of poetry, and two nonfiction books on the relationship of faith and science. You’ve won three awards from the AML, but . . . if you’ll excuse the direction and implication of the question. . . you’re a Biologist, worse a quantitative biologist, or as we in the humanities like to call them, a roustabout, a ne’er-do-well, an organism junkie, a test-tube head, a bug chaser, take your pick. What’s worse you don’t have any writing degrees. You haven’t paid your dues, man. What’s up with that?

AoKLGotLS: Aye. Y’r broken matey, min’ ye, I t’ain’t got a min’ t’argue with ye. Aye. I’s thinks of meself as a hedge witch. Or th’ like.

Steve: A hedge witch? <said with a sneer>

AoKLGotLS: Yes. Beginnings:

You harden on the seventh-grade playground. It has a dark heart. You find the beating thing crouching between the monkey bars and the four-square court. A heart willing to either send tormentors to rob you of your lunch money, or sometimes, to pour down bright luck that leaves you the champion in red-rover or tetherball. The playground is fickle. A space without loyalty. Without honor. In the dark, gritty macadam of the blacktop you either learned to write, or you learn to get a wedgie. No time for nonsense. So there I was at school one day. Sitting in class minding my p’s and q’s, feet on my desk, chewing on a good bubblegum cigar, reading an Archie and Veronica comic and getting ready for my 7th-grade class to start when this dame walks in and says she’s going to change my life. She introduces herself as Ms. Clements. She walks over like only a teacher can and plops down a book and pulls me in by the lapels and says, look kid, it’s poetry, see? Learn it. It started to rain. The drops sounded on the tin roof like a drum portending things we’re about to change. I look out the window from my desk out at the playground and I see the cold hard basketball court starting to soak, the chain-netting of the hoops shaking in the wind. In the distance, I see the mocking yellow buses starting their engines readying to take us home. All this meant nothing. I’d been given a challenge. And so it began. My life as a writer. I rose to meet it. I learned all I could. I dug in deep. I followed the clues. Then I wrote up my findings in the form of a seven-page epic poem about a weasel. The dame was impressed. Said I had talent. Had me read it to the class. Made a bully cry. It’s then I knew words had power. And I intended to use it.

Steve: A hedge witch? <said with a sneer>

How did I become a writer? Sometimes in the morning as I awake, the question arrives crawling from my dreams to tease or perhaps haunt me, and demands an explanation. How did I become a writer? The query appears not full-bodied, not all at once, but from the side, slowly seeping into consciousness mixed with the visions of the night, catching me unawares as it steals into my waking mind carefully like a child sneaking into a room where grownups are talking after a delicious meal, the child wishing to claim a piece of the Tarte Tatin sitting on the counter waiting to be taken into the dining room. On such mornings, however, My mind is slow to respond to the demands that I awake and I enter a hazy state in which sleep and wakefulness seem to flit back and forth like some morning bird unsure whether to stay roosting snuggly among its companions or rise to the day to find the proverbial worm. I look back and see threads of my writing life like paths that follow ancient ox trails set down by the arbitrary ways of some ancient tender of livestock, like the road from Combray to Grand-Pré. I lay back on my bed and certain memories creep to the fore and I recall the young Army private on a troop train going into the fields of Germany to play at maneuvers with a little notebook of stories he was writing. I remember long slow days at BYU where Susan Ream my creative writing teacher and only formal training led me to place in the Mayhew Contest. There was the Leslie Norris forum on Dylan Thomas that turned me eagerly towards poetry. Then the path of my writing career unfolded with writing groups many and varied. In graduate school I worked with English grad students at UNC-Chapel Hill, then southern writers in Raleigh, nature writers in Hawaii, speculative fiction writers in Utah, and always, always I was writing, seeking critiques, and reading. Voraciously. And my books! Oh my, even their smell brings back memories of their contents and places that exist only in my mind. Books infusing every space I’ve lived with meaning and delight, their presence providing the matrix and context for my writing life. I lay back on my bed and ponder the question that many have asked me, Have I paid my dues to be a writer? Or am I more like the cuckoo bird, who I’ve heard on many a spring mornings singing softly in the trees outside my window? This bird who lays her eggs in the nest of a robin where its young can be raised by that other bird. The cuckoo is a usurper who gets to live its life without effort. By sheer luck or cunning, it grabs the resources from the more deserving? So it seems to some, who see a biologist somehow become a writer full-blown without the usual path of training. A hedge witch who has been denied the gates of both Hogwarts and Brakebills1. Or who in the attempt at mastering the craft should be ignored for lack of credentials, like Jude the Obscure who mastered Greek and Latin and yet is turned away from academia, lacking the requisite privileges and connections, and so finds the gates of Christminster ever closed. So yes, I suppose I am the writing equivalent of a hedge witch. But if Brakebills has taught us anything, it’s that a good hedge witch can capture different powers. Often surprising.

Steve: Fine. <yawning> You’re rambling. Tell us about Leere.

Continued at By Common Consent.

Steven Peck is a Brigham Young University biology professor and teaches classes on ecology, evolution, and philosophy of biology. He has published over 50 scientific articles in the fields of evolutionary ecology and philosophy of biology. He has published two books exploring science and religion. The first was Evolving Faith published by the Maxwell Institute; the second was, Science the Key to Theology, published by BCC press. In Summer of 2018 he with Terryl Givens led The Bushman Summer Institute for the Study of Mormon Culture at the Maxwell Institute to explore the relationship between science and the Latter-day Saint thought. During the summer of 2019 Peck will be joining the Maxwell Institute as a Research Fellow to study the relationship between faith and science.

His creative works include three literary novels including the magical realism novel, The Scholar of Moab, published by Torrey House Press—named the Association of Mormon Letters’ (AML) best novel of 2011 and a Montaigne Medal Finalist (national award given for most thought-provoking book). His novel Gilda Trillim, Shepherdess of Rats, was winner of the 2017 AML novel award, and was a finalist for the Whitney award for adult fiction. His soon to be published novel, King Leere Goatherd of the La Sals, was a semi-finalist for the Black Lawrence Press Big Moose Prize for literary novel, which received a starred review from Publishers Weekly; it will be released in Spring of 2019. His novella A Short Stay in Hell, continues to have a large following and remains his most popular book and audio book.

His book of short stories, Wandering Realities was a finalist for the AML award for short fiction collection, and contains his AML award-winning short story, “Two-dog dose“, originally published in Dialogue. His short stories have been published in many venues and widely anthologized. In addition to his collection Incorrect Astronomy, his poetry has appeared in New Myths, Pedestal Magazine, Prairie Schooner, Red Rock Review, and other places.