*Note: I fully support the prophet and his counsel that we use the term “Members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints” when we are referring to members of the Church. In this piece, I’ve decided to use the term “Mormon” because I am referring to a shared culture as much as actual membership.

I made the decision a few years ago to stop fighting my inclination to be very “Mormon” in my writing. I decided, in fact, to embrace my religious background and influences in my work. Some people question that choice, but it’s been the right one for me. I’d like to share some of my reasons for this choice.

First of all, Mormonism is what interests me. (And an artist is at her best when she is writing from her interest, her passion, her curiosity, her heart.) The fact is, it’s worth writing about. Mormonism is endlessly fascinating. It’s strange and wild and beautiful and, yes, sometimes frustrating and provincial and musty. It’s quirky and awesome (in the original definition of that word), detailed and huge. There is so much to explore, both in terms of cosmic philosophy and intimate personal application. Eons, constellations, temples—and the crumbs at the bottom of a church tote bag. In fact, the best simile I can come up with for Mormonism is that it is like a good poem: it touches the eternal through the quotidian. (My poem “Utah Mormon” touches on this, so I’ve included it below.)

Related to this is my second reason: Mormonism is what I know. We’ve all heard the saying that writers should “write what they know.” The fact that we are all human means that there is an awful lot I know about life that applies to all humans, but I can’t deny that I have a worldview that is inescapably Mormon. I was born into it. I can’t remember a time when I didn’t believe that my spirit existed before this life and will exist after it. And I can’t write beyond that, even if I try. But I don’t want to try.

Third, and maybe most important: I believe that Mormons are worth writing for. True, some of them are suspicious of art, believing that the only good art is Deseret Book-sanctioned art that has a clear message and no unsettling elements. Such readers may have difficulty recognizing artistic quality separate from message. Others feel fine consuming art that doesn’t relate to their religion—in fact, they prefer it, doubting that anything Mormon-ish could be satisfying or even entertaining. But there is such a thing as artistic excellence in a Mormon-themed work—I’ve seen it. I have friends who are producing it. I’m trying to produce it. It’s still harder to find than I would like, but it’s out there, and more and more of it is being produced. I believe that the Mormon audience, though less used to it than I would like, responds to artistic excellence, even when they don’t understand why one thing is better than another. And they deserve the very best we artists can give them.

Fourth, I think that Mormons are hungry for art that speaks to their own experiences and worldview—starving for it, in fact. So starving that they often consume “art” that isn’t very good but that speaks to their own culture because they don’t know where to find better stuff. They’ll take what they can get.

Finally, I actually believe that if I can do it well, my Mormon-themed art will speak to non-members as well. People recognize truth. They respond in some subconscious way to a true story, even when they struggle with its premises (which is why we can feel truth in good science fiction, for example). When we tell the truth of our experience, even—or especially—a very specific truth, and do it well, it appeals to people outside of that experience, too. Our souls sense truth, even when it’s someone else’s truth, and respond to it. People outside the church may not understand everything that’s going on in one of my temple poems, for example, but if I write it well, they can understand and access the poem’s yearning for a transcendental experience, and the juxtaposition of human and holy.

As a side note, I should mention that my involvement with the Association for Mormon Letters beginning in the 1990s was not incidental to my growth as a writer. I began thinking seriously about the things that would make their way into my poetry because of conversations on the early AML-List. And I began trying to craft those ideas into poetry because of the work Chris Bigelow and Harlow Clark were doing with Irreantum.

Following my heart in my work makes me more interested in it and, I think, better at it. I also think it has made me more productive. It is like manna: when I use up, trust in, and take care of what I have with all my heart, God sends me more. I find this a beautiful way to work, and to live.

Utah Mormon

The people you want for employees

but not friends. Big families

too shiny for belief—we must

be paper dolls. Look at me: I’m heavy

books, white teeth, organ music

and casseroles, but I crank

up the radio in my car same

as you, scream at God

sometimes, haul myself

bedraggled through awkward

misunderstandings. Half of me

fears you see me as wacko;

half of me knows you don’t

see me at all. Still, I’ll smile

my big white teeth. I’m the suit

and the dress, spires and spurs.

I am my people, bonneted,

ancient, dusty as sage,

but tangy. Let me get close

and you’ll hear the shiver

of juniper, the cricket’s

dry thrum. I carry

a landscape in my blood, brown

haunted by green. Scrub oak

fringes my dreams, and out there,

across a weed-scrabbled

mountain valley, the cottonwood

advertises a riverbed, probably dry.

Always the possibility of a house

sheltered there, always at a distance.

I never arrive. The longing

becomes the destination, sweet

in its way. Without the motion

I’d be bereft: Eve stuck

forever in a garden going

nowhere. Mormon

is the horizontal of the flinty earth,

the vertical of spires. Every year

a camp-out; every year the farm.

We can’t escape the land

but it is never an end.

Permanent nostalgia, a home

made of homesickness.

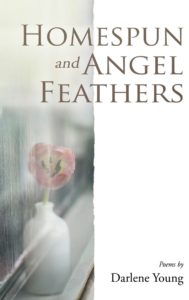

(This poem is used by permission from BCC Press, who will be publishing my forthcoming book, Homespun and Angel Feathers, on May 6. This poem, and many others that speak to our culture, will be included.)

Darlene Young is a poet and essayist, who teaches creative writing in the BYU English Department. She is the poetry editor at Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought. She lives in South Jordan, Utah with her husband and sons.

I’m so glad you gave in, Darlene. The results have been fantastic. The two poems over at BCC are astounding, but I like this one best. It says something that needed to be said, but does it slyly.

Thanks, William!