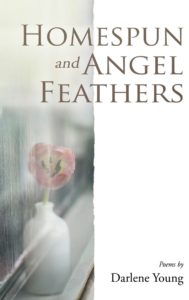

Title: Homespun and Angel Feathers

Title: Homespun and Angel Feathers

Author: Darlene Young

Publisher: BCC Press

Genre: Poetry

Year Published: 2019

Number of Pages: 84 + x

Binding: Paperback

ISBN13: 978-1-948218-17-7

Price: $9.95

Reviewed by Jenny Webb for the Association for Mormon Letters

The first time I read Darlene Young’s vibrant poems in Homespun and Angel Feathers, I laughed (a lot), cried (enough), and carefully folded down the corner on the page of each poem that went beyond the normal “Oh this is a great poem” reaction and on into the realm of “Oh, this is my poem—written for me, right now, and in the future, because I know I’ll be back.” Normally I leave a collection this length (there are 58 poems in total) with two, maybe three pages thus marked. Hardly ever more than five. My count upon finishing Young’s book? Fifteen.

To begin with, the poetry is solid. Young’s a wordsmith, striking while the iron is hot, and sparks fly as a result. She gives us the “torque and tonnage of dailiness” (27) in these poems, examining the ordinary to see if it reveals beauty, or humor, or even better: both. At times she steers straight at the holy, only to have the wholly human emerge as a result—prophets communing with God? Sounds like a pretty serious topic. In “Kintsukuroi for Joseph Smith” he becomes “Hick and height, / scrub and scripture, limp and lamp, he was a handshake / with the heavens … Not immaterial / his fumble and slop, his gimpy stuttering lope towards loft” (8). I’ve got my own “gimpy stuttering lope towards loft” to contend with, and that’s just the point for Young—we’re all shuffling towards God, prophets included.

Young sets her poems all about, in the places and times of a busy, devoted life that tries to pay attention to where it’s at. Her poems are titled “Twenty miles south of Malad, Idaho,” “To a Red Traffic Light,” “My son’s guitar class,” “In the Locker Room at the Temple,” “From Under My Desk at James E. Moss Elementary, 1981,” and my favorite “Depeche Mode in the Produce Section.” These seemingly mundane locations are punctuated with the witness of the way Young’s life has been shaped and contoured by a series of relationships both intimately particular and simultaneously universal: “On Living With a Teenager,” “The Guys I Didn’t Marry,” “Waiting at the Airport for Her Missionary Son,” “Marriage,” and “My Teenager Gets His Wisdom Teeth Out.” A consistent undercurrent of lived faith anchors Young’s poetry in the messiness—the joy and pain and service and sustenance—of a religious life. She considers Gethsemane, the tomb, the well, and the garden; she takes us to the temple, but it’s a sacred space filled with the banality of locker rooms and forgotten words.

I think it’s Young’s ability to work with the material that she’s been given—in life, in words, in faith—and hold it up with care, cradling the divine and the ridiculous with the same affection and love, that I’m drawn to in this collection. Everyone’s crowded together in the family minivan in “Frodo Escorts Us to the Campground Via Audiobook,” and the shepherds watching their flocks are “foul-smelling, lusty / men with dirty necks, greasy hands; snorting, arguing, joke-telling, nose-picking / men—one wearing stolen / sandals (although I admit he felt / guilty about it)” (6). The women in the Seventh Ward Relief Society try to decide whether a sister’s family should receive meals after her recent surgery (“no one was sure if ‘boob job’ qualified / as a legitimate call for aid” [9]) and if that makes you smile, wait until you get to the end (it’s just too good to give away here, sorry). Consider the delicate beauty and gut-punching truthiness wound around the wry, winking core of “‘Lord, Make Me an Instrument of Thy Peace’”:

Ok, let’s get this straight. When I said it,

I meant tool. Tackle, widget, implement, device.

Something cool and sharp with important work to do:

a screwdriver, maybe. Scalpel or forceps.

Ophthalmoscope. I would have settled for tweezers,

chopsticks—heck, even a toothpick has its dignity and place

(raspberry seed, lunch with the boss).

Or, if we’re thinking music, how about a harp

or piano? I could pluck and finger thy word

for the world. But I’m clumsy; I get that. Then

why not go large, with chimes, or a kettle drum?

Or a sassy trumpet, blazing with thy breath?

Sure, I’m not gong-strong, nor flute pure, but maybe

I could be bagpipes—or viola, the plain older sister?

Moving into middle age, I begin to see the joke

and joy of what you’ve made of my life: yes,

your breath has been in me, and on days

I manage to flatten myself thin enough,

translucent as waxed paper, I vibrate,

resonant in your wind. You humming through me:

curious timbre. Ticklish, tangy, and strange;

good enough. I’ll be your holy kazoo. Selah. (1)

This is the kind of holiness that hits home: painfully funny (I can’t get through it without actually chuckling out several of those short, barking laughs that let the author know they’ve successfully made their point) and, in the end, unmistakably true. We’re all kazoos here, with all the beauty and humor the metaphor implies.

I could go on, but at this point, if you’re going to be reading, I promise both you and I will be happier if it’s something out of Darlene Young’s Homespun and Angel Feathers. I can gush all I want, but the truth is, after writing this review, I’m anxious to dive back in and visit those pages I marked. Go get this book—for yourself, and a few copies to share. You won’t regret it, and if you’re like me, you’ll be eagerly awaiting more.

Thank you for a beautiful review, Jenny. I’m writing for a niche within a nice–the audience is small, and it’s hard to reach them. Thanks to you for spreading the word and, especially, to BCC for publishing.

These touch my soul! Thank you for sharing your talent.