“Can YOU pass the Acid Test?”

“Can YOU pass the Acid Test?”

—Merry Pranksters, quoted in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test

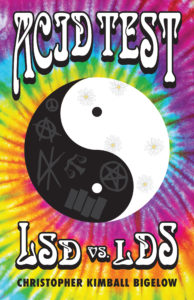

Acid Test: LSD vs. LDS is a memoir of my mid-1980s spiritual journey. The book relates my experience with what I eventually figured out were the dark and light sides of an unseen spiritual dimension. At first, I was just going to tell the tale of my wild years and then have a concluding chapter about getting spooked by the dark side and retreating back into Mormonism. As I wrote, however, and received high-quality feedback from pros, I found myself equally interested in portraying my struggle to find palatable ways to embrace Mormonism. Some readers enjoy the book’s initial dark half better, and others prefer the light side in the second half, but I see the two sides as necessary to explore together, in the correct order. As the title and cover suggest, this book is propelled by duality and juxtaposition. I appreciate what D. Michael Martindale wrote: “The tale seems to ramble from one disjointed thing to another at first, but slowly over chapters, you notice a pattern emerging, a plot arc arising from the punk chaos, and you realize [Bigelow] is an accomplished storyteller who knows what he’s doing without letting on.”

With Acid Test, I wrote a book that I would want to read, rather than trying to target a certain readership or market. I call it a memoir, but it could also be tagged as an autobiographical novel. The reader goes through the story as if in real time with the protagonist (my late-teens self), rather than receiving it filtered through a present-day interpreter and judger. But I don’t like the term “novel” because it implies the book could be mostly fiction, and I definitely consider this book nonfiction. Like any memoirist, I reconstructed things, especially dialogue, but I did so to the best of my memory, refraining from consciously fictionalizing. (In a couple of cases, I couldn’t remember where an event fit in the chronology, so I placed it where it was most dramatically useful.) I learned that when you reconstruct a memory, your brain starts to turn the reconstruction into what feels like real memory, and you can never again be sure which is which.

Sometimes I think writing a memoir is simply a way to crowdsource your own psychoanalysis. I can be a somewhat exhibitionistic person, and my aim was to make Acid Test a fully confessional account, an exercise in “radical disclosure,” as I’ve heard it called. Not only is Acid Test somewhat of a passive-aggressive response to repressed Mormon culture, but I’m also admittedly influenced by today’s mega-transparency and micro-shame (for me, exhibit A would be the comedian Louis C.K.). I’m also inspired by my favorite author, John Updike: “I’m willing to show good taste, if I can, in somebody else’s living room, but our reading life is too short for a writer to be in any way polite. Since his words enter into another’s brain in silence and intimacy, he should be as honest and explicit as we are with ourselves.” I included almost no profanity and not a single dreaded F-word, because I didn’t want to give Mormons such an easy excuse for not reading it, but I did include some drug experiences and nonpornographic accounts of sex, the most notorious of which involves Crisco. I wanted readers to go through the dark side with me and experience how it impacted me, so I could dramatize why a Mormon kid could get caught up in such misadventures and explore reasons—and perhaps suggest some blame—for his spiritual confusion and alienation. Unless a reader finds the content provocative in an entertaining way, perhaps similar to how true-crime stories can be compelling, it may be a challenge to get through the book’s dark first half. Personally, I think some of the book’s most disturbing and most funny parts both have to do with sex.

I consider Acid Test as ultimately an expression of faith, a bearing of testimony. Nonetheless, I haven’t yet had an “active” Mormon outside my family express robust appreciation and acceptance of the book, although it’s still early days. However, I have started getting fans from outside the faith, and maybe that’s where the book’s readership mostly lies, if it has one at all. “An honest, entertaining, and moving expression of what it is like to be a human being,” wrote the director of the Institute for the Advancement of Psychedelic Christianity (I love that this organization exists). “I felt happy while I was reading it.” As I tested earlier drafts, my most enthusiastic proponent was a novelist who grew up Mormon but later became an atheist. My drug-pusher friend depicted in the memoir said the book spoke to him as, thirty-five years later, he now tries to move forward with his long-time girlfriend who recently returned to Mormonism. I also appreciate what Kirkus Reviews wrote: “While the author is an able storyteller with plenty of colorful anecdotes, his interest in morality provides a unique ballast in what would otherwise be a typical but entertaining tale of adolescent mischief. His evocative depiction of the time and its subcultures helps make this a memorable and ultimately quite surprising autobiography.”

I plan a follow-up volume called Zion Test, in which I try to find a place within corporate Mormonism and then branch out into independent, alternative Mormon avenues, ultimately meeting a guru who extrapolates from the Joseph Smith Papers to show how the LDS church could decentralize its structure and thus transcend its corporate and cultural failings. Earlier, I was planning a memoir trilogy with Mission Test as the middle volume, but I decided I don’t need a whole book about my mission—though it would be fun to write—because so many others have already depicted that experience.

Christopher Bigelow began his career as an editor at the LDS Church’s Ensign magazine. A graduate of Emerson College and Brigham Young University, he co-founded and edited the Mormon literary magazine Irreantum and the satirical Mormon newspaper The Sugar Beet. He is the author, co-author, or editor of seven books on Mormonism, including a novel, with more on the way. He has received an editing award and an honorary lifetime membership from the Association for Mormon Letters. He runs the small Mormon press Zarahemla Books and works as a freelance writer, editor, and instructor.

Christopher Bigelow began his career as an editor at the LDS Church’s Ensign magazine. A graduate of Emerson College and Brigham Young University, he co-founded and edited the Mormon literary magazine Irreantum and the satirical Mormon newspaper The Sugar Beet. He is the author, co-author, or editor of seven books on Mormonism, including a novel, with more on the way. He has received an editing award and an honorary lifetime membership from the Association for Mormon Letters. He runs the small Mormon press Zarahemla Books and works as a freelance writer, editor, and instructor.