By Moe Graviet

By Moe Graviet

An essay for the BYU “Literature and Spirituality” course, taught by Matthew Wickman.

A few months ago, my Baba told us that she was going to sell the house.

This probably shouldn’t have shook me up as much as it did, but I felt an acute sense of loss. Selling the house meant that she was going to sell the home my mother had grown up in; the room where she had taught me how to sew; the roof where we unclipped fresh laundry soaked in sunshine, piece by piece; the tatami mat that Yuki, Mika, and I would lay on and breathe in sunny nuttiness in the summer time; the kitchen where she taught my mother and then me how to fold gyoza after the way of the women in our family; the cement street with little holes carved into it that my mother and aunt used to walk down everyday for school; the bathtub where she sprinkled peels from a giant grapefruit for scent; the garden that smelt like time with its moss-covered rocks and Japanese maple trees; the shelves of pickled red plums with shisou that we made every summer; the closet that housed our butsudan with my great-grandmother’s smiling picture.

Selling the house felt like an acceleration of the loss of culture and self that I had been feeling in recent years and didn’t know how to mitigate. I realized that my grandparents would eventually pass on and our culture might die out in our family with me, as one of the few grandchildren, and future generations. And I was already losing it myself—my Japanese had been slipping since my mission; no matter how much I tried, the kanji never quite stuck. If I ever had kids, they would never experience any of what I had known. They would never know that garden smell, would never see themselves in their ancestors at the family butsudan, or know the Japan that I knew—that my mother knew—that my grandparents knew. Our heritage would only become a memory. Selling the house meant that my last tangible tie to Japan, to my Japanese heritage, would be cut; and that despite my best efforts, I would lose that part of my self.

As I have grown older, I have become acutely aware of a distancing between myself and my heritage—I am always trying to bridge this gap and to exist alongside a feeling of inevitable loss as our ties have stretched thinner. I have a fear of losing my self, because that self dwells in a web of connectedness, and I’m going to lose specific thing-events—my grandmother, mother, and language—that constitute that connectedness as the years go on. Who will I be afterwards? When you dwell in the space between things and one of those things disappears, what happens then? How do we navigate knowing that there are things that we simply cannot help but lose, despite our best efforts?

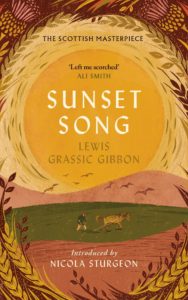

In Sunset Song, Lewis Grassic Gibbon paints Chris Guthrie as a character who is incredibility sensitive to the spirit of things, often tapping into the spirit of places and peoples—especially her homeland of Scotland. On a trip with her husband Ewan to the castle by Drumtochty Hill, Chris has a transformative experience as she senses things—and people—that have passed on:

In Sunset Song, Lewis Grassic Gibbon paints Chris Guthrie as a character who is incredibility sensitive to the spirit of things, often tapping into the spirit of places and peoples—especially her homeland of Scotland. On a trip with her husband Ewan to the castle by Drumtochty Hill, Chris has a transformative experience as she senses things—and people—that have passed on:

But Chris didn’t laugh at him, she knew right well that such beasts had never been, but she felt fey that day, even out here she grew chill where the long grasses stood in the sun, the dead garden about them with its dead stone beasts of an ill-stomached fancy. Folk rich and brave, and blithe and young as themselves, had once walked and talked and taken their pleasure here, and their play was done and they were gone, they had no name or remembered place, even in the lands of death they were maybe forgotten, for maybe the dead died once again, and again went on (Gibbon 166).

In her mediation upon the people who have lived and gone, Chris seems to commune with time. She reaches back through years of living and memory and superimposes the past upon the present, layering and pressing the folds of time together into a single sheet. In her pondering, her ancestral countrymen, even those who have passed and been “forgotten,” regain life and influence and seem to reach through the centuries to touch, to move her—and become part of her.

The connectedness that Chris is able to find through spirituality, to both past and present simultaneously, has an intensifying, heightening, occasionally even dizzying effect. It also invokes the idea of generational living—that narratives do not dissipate, but form anew as a type of spiritual heritage. The passage from Chris’s wedding is another that evokes similar thoughts:

It came on Chris how strange was the sadness of Scotland’s singing, made for the sadness of the land and sky in dark autumn evenings, the crying of men and women of the land who had seen their lives and loves sink away in the years, tings wept for beside the sheep-buchts, remembered at night and in twilight. The gladness and kindness had passed, lived and forgotten, it was Scotland of the mist and rain and the crying sea that made the songs…(Gibbon 158).

As Chris weaves a connectedness between “Scotland’s singing’ and the land’s sadness in “dark autumn evenings,” the cries of women and men, weepings, joys, kindnesses, and Scotland itself, bringing them all together, her passage seems to exemplify Wesley J. Wildman’s second definition of a spiritual experience as a “rich interconnection of ideas, memories, and emotions that weaves normally separated parts of life into a single field of meaning” (105). “Scotland’s singing” becomes a connecting factor for various parts of life and land, allowing Chris to tap into deeper, spiritual underpinnings imbued in the place. Through her sensitivities and spiritual attunement, she seems to tap into the soul of Scotland itself. She seems to establish a robust, grounded sense of self in the connection of these things, finding home and meaning in the living influences of both tangible and intangible entities.

As Chris weaves a connectedness between “Scotland’s singing’ and the land’s sadness in “dark autumn evenings,” the cries of women and men, weepings, joys, kindnesses, and Scotland itself, bringing them all together, her passage seems to exemplify Wesley J. Wildman’s second definition of a spiritual experience as a “rich interconnection of ideas, memories, and emotions that weaves normally separated parts of life into a single field of meaning” (105). “Scotland’s singing” becomes a connecting factor for various parts of life and land, allowing Chris to tap into deeper, spiritual underpinnings imbued in the place. Through her sensitivities and spiritual attunement, she seems to tap into the soul of Scotland itself. She seems to establish a robust, grounded sense of self in the connection of these things, finding home and meaning in the living influences of both tangible and intangible entities.

Thinking through my own questions of identity and Chris’s experiences has helped me to understand that perhaps spirituality is so important to me because I ultimately see it as a bridge between parts of myself that cannot connect, or a thing that makes space for me to live in and to find connectedness within lives and selves that do not align—even thing-events that have passed on. This connectedness does not rely on the physical presence or “live-ness” of thing-events, but can reach back through memory and touch them still. Just as Chris is able to find a deeper grounding in the connectedness that spirituality facilitates, spirituality is the medium where “I” meet; and in many ways, I see it as the binding agent of my selfhood. The meeting place where unlikely places can connect and find a home.

One of the most important things I’ve learned in this course is that spirituality is not just a medium where things are collected—it’s a place where things live. Through it, we are able to feel the wholeness that comes from the unification of the multitudinous facets of ourselves and our lives—both physically present, and intangible or beyond the veil. To me, spirituality means that nothing is ever truly lost.

.

The structure of this essay is topnotch. I just recently heard of “Sunset Song” but hadn’t developed an opinion whether or not I should seek it out. I take it the answer to that question is yes.