By Liz Busby

This is the second of a five-part series on Mormon speculative fiction.

In my previous post, I talked about how Mormon speculative fiction really started in the 19th century with religious speculative fiction in the vein of Nephi Anderson’s Added Upon. This type of story continues through to the present day with works like Saturday’s Warrior and Tennis Shoes Among the Nephites, but it is hardly the main branch of the Mormons and science fiction story. For that story, let’s make a brief stop in the era of pulp science fiction before heading on to the main event in the 1980s.

Pulp-Era Mormon Science Fiction

Science fiction as a genre really began to take off in the early to mid-20th century, marked by the rise of the science fiction magazine. Dozens of serial magazines created a lively market for “pulp” science fiction short stories. Among the dozens of new writers were two Mormons of particular note, and the relationship between their faith and their writing characterizes the two primary modes of later Mormon science fiction writers.

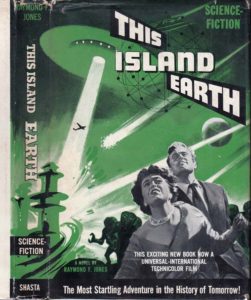

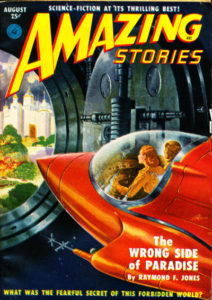

First, Raymond F. Jones, a Mormon living in Sandy, UT, was a prolific writer of short stories and novellas during this period. He is best known for his novel This Island Earth (Chicago: Shasta, 1952) which was the basis for a science fiction movie of the same title. Though his short stories show little explicit connection to Mormonism, they were part of a wave of more

First, Raymond F. Jones, a Mormon living in Sandy, UT, was a prolific writer of short stories and novellas during this period. He is best known for his novel This Island Earth (Chicago: Shasta, 1952) which was the basis for a science fiction movie of the same title. Though his short stories show little explicit connection to Mormonism, they were part of a wave of more  human science fiction, which focused on how technology would affect human behavior and society. Jones’ type of Mormon science fiction—one containing a general care for people but not any specifically Mormon themes or subjects—was the first example of a mainstream science fiction writer who happened to be Mormon, a type of writer which would explode in the eighties and nineties to include such writers as Tracy Hickman and Dave Wolverton/Farland.

human science fiction, which focused on how technology would affect human behavior and society. Jones’ type of Mormon science fiction—one containing a general care for people but not any specifically Mormon themes or subjects—was the first example of a mainstream science fiction writer who happened to be Mormon, a type of writer which would explode in the eighties and nineties to include such writers as Tracy Hickman and Dave Wolverton/Farland.

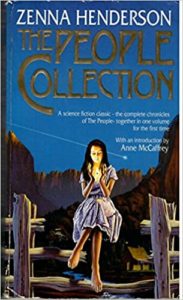

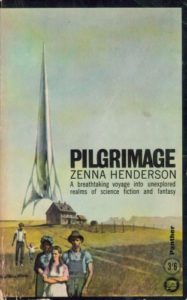

Ironically, the short stories of inactive Mormon Zenna Henderson from the same period show a more obvious LDS influence. In 1951, she published the first of her “People” stories. They featured an alien race, dubbed “the People,” who were forced to emigrate to Earth because of the impending  destruction of their home planet. Landing in the southwestern United States, the People established a society separate from humanity both to preserve their unique culture and to prevent persecution because of their unique psychic gifts.

destruction of their home planet. Landing in the southwestern United States, the People established a society separate from humanity both to preserve their unique culture and to prevent persecution because of their unique psychic gifts.

The analog to the flight from Nauvoo and establishment of Utah by the early Mormons is obvious, though it has apparently never been commented on by scholars, perhaps because the LDS faith of her childhood is not widely known. However, its echoes in her stories illustrate a second path of Mormon science fiction  writers, followed most notably by Orson Scott Card who has listed her as an influence on his work. Although Henderson never achieved bestseller status and is mostly unknown to Mormon readers, her stories were quietly and consistently published in prominent science fiction magazines throughout the 50s, 60s, and 70s. These stories inspired a 1972 TV movie The People, starring William Shatner. The most recent collection, titled Ingathering, is still in print and available on Amazon.

writers, followed most notably by Orson Scott Card who has listed her as an influence on his work. Although Henderson never achieved bestseller status and is mostly unknown to Mormon readers, her stories were quietly and consistently published in prominent science fiction magazines throughout the 50s, 60s, and 70s. These stories inspired a 1972 TV movie The People, starring William Shatner. The most recent collection, titled Ingathering, is still in print and available on Amazon.

The Rise of Orson Scott Card

The origin story of Mormon science fiction really begins to pick up in 1977, when Orson Scott Card began publishing his first science fiction stories, including the short story version of “Ender’s Game.” He studied drama during his undergraduate years at BYU and saw himself mostly as a playwright. He also wrote for the Ensign, but was struggling to make ends meet. In order to get a little cash, he began to submit science fiction short stories to Ben Bova at Analog magazine and was soon offered a book deal. The direction of his future career started to become evident when he won the 1978 Campbell Award for best new science fiction writer. You can hear more of Card’s version of this story on episode 56 of the Writers of the Future Podcast.

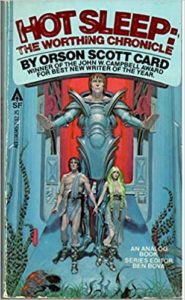

In the next few years, Card published several other science fiction novels, including Hot Sleep, the first novel length incarnation of what would eventually become Card’s The Worthing Saga. The story has a distinctly Mormon ring, as the main character Jason Worthing becomes the de facto god of a new colony planet (the memories of the other colonists having been erased). He must therefore shape the morality of the new society. The book’s central focus is on the need for opposition in all things, a message pulled straight out of 2 Nephi 2. Reading the book, I was shocked at just how Mormon the worldview of this book is, though it has received less scholarly attention than his more popular works.

In the next few years, Card published several other science fiction novels, including Hot Sleep, the first novel length incarnation of what would eventually become Card’s The Worthing Saga. The story has a distinctly Mormon ring, as the main character Jason Worthing becomes the de facto god of a new colony planet (the memories of the other colonists having been erased). He must therefore shape the morality of the new society. The book’s central focus is on the need for opposition in all things, a message pulled straight out of 2 Nephi 2. Reading the book, I was shocked at just how Mormon the worldview of this book is, though it has received less scholarly attention than his more popular works.

The Class That Wouldn’t Die

In 1980, Card was scheduled to teach a creative writing class at BYU to focus on science fiction writing, which generated much excitement among the student body. Several science fiction courses had recently been added to the curriculum in the English department in an attempt to draw more students to the declining major. Between Card’s success and the Mormon references in Battlestar Galactica on television, interest in the genre was high.

When Card instead moved his family to Indiana to pursue further education, the responsibility for teaching the writing class was shifted to Marion K. “Doc” Smith. The result was one of the most told stories in the history of Mormon science fiction. At the end of the semester, the class morphed into the Xenobia science fiction writing group, the longevity of which earned it the title “the class that wouldn’t die.” The group continues to meet today, and several members of Xenobia have gone on to notable speculative fiction writing careers, including M. Shayne Bell of the original group and Dave Wolverton, who joined the group in its later years.

When Card instead moved his family to Indiana to pursue further education, the responsibility for teaching the writing class was shifted to Marion K. “Doc” Smith. The result was one of the most told stories in the history of Mormon science fiction. At the end of the semester, the class morphed into the Xenobia science fiction writing group, the longevity of which earned it the title “the class that wouldn’t die.” The group continues to meet today, and several members of Xenobia have gone on to notable speculative fiction writing careers, including M. Shayne Bell of the original group and Dave Wolverton, who joined the group in its later years.

However, the real contribution of the Xenobia group was the founding of two key establishments at BYU which would greatly enable the Mormon science fiction movement. The first was The Leading Edge magazine which began publication in 1982. Though originally a student journal of questionable quality (the first issue was produced on a Xerox machine with two different colored covers because they ran out of green paper), The Leading Edge has become an institution in BYU’s English Department, rising to the level of a semi-professional magazine, even paying for the submissions they accept. The journal has served as a jumping off point for many new Mormon science fiction writers including Dave Wolverton/Farland, Brandon Sanderson, and Dan Wells. Orson Scott Card also published some short stories in The Leading Edge, perhaps because they are too overtly Mormon for mainstream journals.

However, the real contribution of the Xenobia group was the founding of two key establishments at BYU which would greatly enable the Mormon science fiction movement. The first was The Leading Edge magazine which began publication in 1982. Though originally a student journal of questionable quality (the first issue was produced on a Xerox machine with two different colored covers because they ran out of green paper), The Leading Edge has become an institution in BYU’s English Department, rising to the level of a semi-professional magazine, even paying for the submissions they accept. The journal has served as a jumping off point for many new Mormon science fiction writers including Dave Wolverton/Farland, Brandon Sanderson, and Dan Wells. Orson Scott Card also published some short stories in The Leading Edge, perhaps because they are too overtly Mormon for mainstream journals.

The Xenobia group also founded BYU’s science fiction and fantasy symposium, which soon took the name Life, the Universe, and Everything (or LTUE), after the book by Douglas Adams. Since then, the symposium has maintained a continuous presence in Utah County, bringing high profile science fiction and fantasy writers and editors to BYU each year. The early years of the conference began “with an emphasis on the question, ‘Why would a Mormon want to write science fiction?’” (Parkin, Scott. “A New Mormon Battalion: The Rise of Speculative Fiction Among Mormon Writers.” Annual of the Association for Mormon Letters 1998).

The Xenobia group also founded BYU’s science fiction and fantasy symposium, which soon took the name Life, the Universe, and Everything (or LTUE), after the book by Douglas Adams. Since then, the symposium has maintained a continuous presence in Utah County, bringing high profile science fiction and fantasy writers and editors to BYU each year. The early years of the conference began “with an emphasis on the question, ‘Why would a Mormon want to write science fiction?’” (Parkin, Scott. “A New Mormon Battalion: The Rise of Speculative Fiction Among Mormon Writers.” Annual of the Association for Mormon Letters 1998).

Unfortunately, the conference did not begin publishing its proceedings until 1993, so much of the early thought generated about the Mormon/science fiction connection is lost, though some was published in The Leading Edge magazine. (This series of blog posts is expanded from a paper I originally presented at LTUE in 2004.) The conference continues today, though it has moved off campus in recent years and has moved mostly off the topic of Mormons in science fiction to a more general convention. Still, the presence of this academic, creator-focused convention has encouraged many would-be speculative fiction writers.

An Explosion of Experimentation

With these three institutions in place (BYU’s Writing Science Fiction and Fantasy class; The Leading Edge magazine; and the LTUE convention) Mormon science fiction was equipped for an explosion in the following decades. The official declaration that Mormon science fiction had come into its own was the publication of Orson Scott Card’s Ender’s Game (1985) and Speaker for the Dead (1986): both novels won science fiction’s top prizes, the Hugo and Nebula awards, in successive years, a feat which no writer has since duplicated. During this period several Mormons won the Writers of the Future contest or received publication in the contest anthology, including M. Shayne Bell and Dave Wolverton in 1987 and Virginia Baker in 1989.

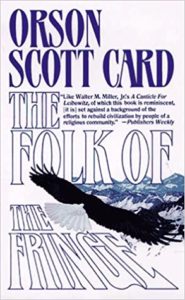

Much experimentation in more specifically Mormon science fiction also began to take off. In 1989, Card published his Folk of the Fringe short story collection, which examines the Mormon religion as a power structure in a future, post-apocalyptic Utah. This theme had been dealt with in a hostile way in mainstream science fiction (for example in Dean Ing’s Systemic Shock), but Card’s attempt presents a view that is radically Mormon as he looks into the possibilities for a future LDS theology which includes the demise of America and the rise of the Lamanites’ descendants.

Much experimentation in more specifically Mormon science fiction also began to take off. In 1989, Card published his Folk of the Fringe short story collection, which examines the Mormon religion as a power structure in a future, post-apocalyptic Utah. This theme had been dealt with in a hostile way in mainstream science fiction (for example in Dean Ing’s Systemic Shock), but Card’s attempt presents a view that is radically Mormon as he looks into the possibilities for a future LDS theology which includes the demise of America and the rise of the Lamanites’ descendants.

Additionally, three collections of specifically Mormon science fiction were published during the late 80s and early 90s entitled Latter-Day Science Fiction. These collections were inextricably tied to Mormon culture: the second volume contains an introductory essay by Hugh Nibley and stories that speculate on missionary work involving time travel and a future church where only women have the priesthood. (A copy with marginal notes by Hugh Nibley can be found in the BYU library’s Ancient Studies room.) These books were of mediocre quality and are generally little known, but their appearance certainly indicates the ripening of the Mormon science fiction movement.

Additionally, three collections of specifically Mormon science fiction were published during the late 80s and early 90s entitled Latter-Day Science Fiction. These collections were inextricably tied to Mormon culture: the second volume contains an introductory essay by Hugh Nibley and stories that speculate on missionary work involving time travel and a future church where only women have the priesthood. (A copy with marginal notes by Hugh Nibley can be found in the BYU library’s Ancient Studies room.) These books were of mediocre quality and are generally little known, but their appearance certainly indicates the ripening of the Mormon science fiction movement.

Next time, we’ll move into current times to examine two modes of mainstream Mormon speculative fiction.

Liz Busby is a writer of creative non-fiction and speculative fiction. She loves reading science fiction, fantasy, history, science writing, and self help, as well as pretty much anything that holds still for long enough. Liz graduated from BYU with a BA in English, and lives in Bellevue, WA, with her husband and four kids. Follow her writing at www.lizbusby.com.

Liz Busby is a writer of creative non-fiction and speculative fiction. She loves reading science fiction, fantasy, history, science writing, and self help, as well as pretty much anything that holds still for long enough. Liz graduated from BYU with a BA in English, and lives in Bellevue, WA, with her husband and four kids. Follow her writing at www.lizbusby.com.

.

Are The People, Pilgrimage, and Ingathering all essentially the same book?

This is really great work, Liz. I didn’t realize LTUE published their conference proceedings in the 1990s. Wish I had had access to them back then.

This reminds me too that Zenna Henderson’s People stories were as Kindle editions back in April of this year.

.

I don’t know who her literary executor is, but reading the reviews on Amazon it’s clear there is a hunger for her books being rereleased in inexpensive lovely forms. Penguin or someone should get on this. She could be their next Shirley Jackson.

Mention might be made also of Samuel W. Taylor, national market novelist and historian as well as a strong proponent for Mormon literature. Taylor is probably best described as tangentially a sci-fi author and mid-century contemporary of both Jones and Henderson on the strength of Taylor’s two short stories published in the national “slick”magazine Liberty that later were adapted into the Disney films “The Absent-Minded Professor,” “Flubber,” and “Son of Flubber.”