The literature scholar Eugene England posted the following essay on the Association for Mormon Letter’s AML-list listserve in March 1997. He produced a shorter, revised version which he gave at the 2000 AML Conference, and was published in the Association for Mormon Letters 2001 Annual as “Whipple’s The Giant Joshua: The Greatest but Not the Great Mormon Novel” (p. 61-69). I have the archives of AML-List for 1997, and was able to retrieve the original essay, which I present here. England had met with Whipple in the 1990s, and bases his comments on her history on what he learned from her (not all of which is correct).

The literature scholar Eugene England posted the following essay on the Association for Mormon Letter’s AML-list listserve in March 1997. He produced a shorter, revised version which he gave at the 2000 AML Conference, and was published in the Association for Mormon Letters 2001 Annual as “Whipple’s The Giant Joshua: The Greatest but Not the Great Mormon Novel” (p. 61-69). I have the archives of AML-List for 1997, and was able to retrieve the original essay, which I present here. England had met with Whipple in the 1990s, and bases his comments on her history on what he learned from her (not all of which is correct).

Whipple’s The Giant Joshua: A Literary History of Mormonism’s Best Historical Fiction

Part 1

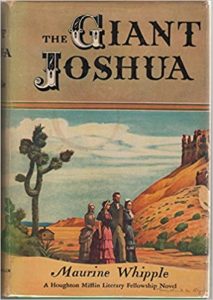

An editor told Maurine Whipple in the 1940s that her novel, The Giant Joshua, was thirty years ahead of its time. The growing interest of the past twenty years, which has made collector’s items of used copies of the Houghton Mifflin first edition of 1941 and the Doubleday paper-back edition of 1961 is a rather precise vindication of that prophecy. That interest led to a hardback reprint, sponsored by Sam Weller of Zion’s bookstore (Western Epics, l976), which is still available, and in the 1980s to work on a film version, which was to be produced by Sterling Van Wagenen (never completed), script (already written) by Brian Capener. The book seems to be finally coming into its rightful prominence for Mormon and Utah readers. It perhaps will even find its place as the minor classic of American literature some early critics prophesied for it. At any rate there is good reason to give it some extended historical and critical attention.

Let me say straight out that I find The Giant Joshua among the finest two or three novels yet produced by or about Mormons. And more, it compares favorably with other, much better known, regional American novels such as Giants in the Earth, Main Street, and even My Antonia. It is not only, as the critic of Western literature, Ray B. West has noted, “the most complete record of a small pioneer community,” [1] but it is also the richest, fullest, most moving, the truest fiction about the Great Basin pioneer experience that I have found.

Let me say straight out that I find The Giant Joshua among the finest two or three novels yet produced by or about Mormons. And more, it compares favorably with other, much better known, regional American novels such as Giants in the Earth, Main Street, and even My Antonia. It is not only, as the critic of Western literature, Ray B. West has noted, “the most complete record of a small pioneer community,” [1] but it is also the richest, fullest, most moving, the truest fiction about the Great Basin pioneer experience that I have found.

Despite the shocked initial reaction to the book in Mormon country, especially in St. George, Laurel Ulrich is right in her comment in Mormon Sisters (1976) that “thirty years later the book seems remarkably true to the faith, an excellent place to begin in developing an understanding of pioneer life.” [2] When the novel first appeared, the reviewer for the Christian Science Monitor singled it out as having “special interest because of the sympathetic treatment of Mormons” [3], and a long review in the New York Times, which called it “rich, robust, oddly exciting,” claimed it “brings Mormons as close home to the reader as they have ever been. They are not only likable, but they have a certain magnificence which fully explains their history.” [4]

West, in his substantial essay in the Saturday Review of Literature, pointed out that Joshua caught a side of the Mormon story missed by Vardis Fisher, “the tenderness and sympathy which existed among a people dogged by persecution and hardship, forced to battle inclement nature and struggle for each moment of happiness.” [5] All this is true enough. And if it is also true, as I was assured by a friend of mine, descended from the pioneers of St. John’s valley (that settlement near Whipple’s St. George which may have been an even tougher place to colonize because it did not survive), if it is true as my friend said that one cannot understand the Mormon experience without understanding the struggle of the Dixie Mission–the human cost and the faith that was willing to meet the cost and the human results won in the struggle, then we have in The Giant Joshua a most direct and perceptive avenue to deeper understanding of Mormon experience. I honor Maurine Whipple for providing our finest fictional access to our roots as Mormons and as Rocky Mountain, high desert people, our most profound imaginative knowledge of our spiritual ancestors, the Dixie pioneers.

Yet we must still continue waiting for the great Mormon novel. Whipple finally remains too much a part of that “lost” generation of Mormon writers of the 30s and 40s Edward Geary has described so well for us, what I have called the second major generation of our serious Mormon writers. Like them, Whipple is properly energized by her independence and disillusionment with her people and Church but not finally reconciled to her characters and subject. Whipple is nostalgic, even able to praise in epic terms the communal strengths of Mormonism, able to see those strengths with unusual insight, but finally, because of her lack of understanding and loss of faith in her own present, unable to keep faith with her ancestors, and thus finally with her own characters. She cannot keep the vision whole, even though she knows it integrated her own people within themselves and in their community in a unique way–and so she cannot bring her work to resolution and the novel loses its quality in the last 100 pages: Her powerful theme of human struggle is fragmented by indecision about what motivated the struggle, her fine central characters are a victim of her own fierce revenge and finally by her even more destructive sentimentality, and the rich, muscular plot is betrayed by a turn to melodrama. It is finally a disappointment of love and faith.

But that the book was written at all is a fair miracle–an evidence of faith and love to which attention must be paid, given the fragile nature of the novelist’s gift and human response to it. Without her knowledge, a friend sent a nearly forgotten manuscript of Whipple’s to a Colorado writers’ conference, and out of the blue she received an invitation to attend. There she remembers being given much attention and extremely flattering praise by the fine Harvard poet and critic John Peale Bishop. Here the story takes on almost mythic qualities: Bishop spending nearly all one night sitting with her on the steps of a fraternity house in Boulder, rejoicing over the unforced humor in her work, the absence of breast-beating and melodrama of self, the honesty, vitality, fidelity to her materials, to her landscape–all so unusual in a first novel. The mythic qualities of the story become tinged with the tragic when we hear it from Whipple or read her 1971 interview in Dialogue, which is full of breast-beating and melodrama of self. According to Whipple, “Bishop told me that I could be one of the greatest women writers of my time, if I had a little help. . . something like a decent environment and some encouragement. . . peace of mind, food, and a place to live. . . , but of course, I’ve never had any of that. That’s been the trouble.” [6] But there was extraordinary encouragement and help for awhile. Ford Maddox Ford, also impressed, asked for first refusal rights on the short novel, and took it to Houghton Mifflin, where a vice-president, Ferris Greenslet, to whom Joshua is dedicated, became Whipple’s editor.

All that could well have turned a young person’s head, but Whipple settled down to the actual task eventually agreed upon with Greenslet–risked moving beyond the security of that highly praised early work called (“Beaver Dam Wash,” a story of the southern oil boom that is still unpublished except in part) and conceived a trilogy on the people of southern Utah from settlement to the present. She supported herself by teaching school and giving tap-dancing lessons after school, which she learned by correspondence one lesson ahead of the students; and she kept up the writing far into the lonely morning hours until she got the first book out. She did this over a two year period, without assurances, and won the Houghton Mifflin Literary Fellowship prize from among thousands of entries (including Carson McCullers and Eudora Welty)–which she says brought her much less respect, or even attention from her friends and family, than if she’d gotten a story published in the Relief Society Magazine or a paragraph in the Deseret News. The miracle is only accentuated by Whipple’s long and so far unsuccessful struggle to write the other two volumes of her projected trilogy.

After her novel was published in late l940 (official publication date 1941) this unpretentious Mormon girl from rural Utah was wined and dined all over the literary East. There were a number of favorable reviews: Joshua was praised by Time magazine, which claimed it “approaches. . . the edge of grandeur,” and by Redbook, which mentioned “courage and tenderness never before put on paper.” It was circulated by the Dollar Book Club, which called it “a first novel that will be part of the permanent body of American Literature,” and for a long time it was the most popular item at the Salt Lake Public Library. Whipple’s own Utah people were apparently curious to read it but not willing to be known as having actually bought such a questionable book. This was probably especially true after the official word came out in February 1941 through the review Elder John A. Widstoe wrote for the Improvement Era.

Elder Widstoe started out mildly enough, praising Whipple’s success in bringing the story of the pioneer battle with the desert to dramatic life with her skillful use of detail and only referring mildly to “a few serious historical errors.” [7] But then, though he gave her credit for showing with a high degree of fairness that polygamy rested on high spiritual motives, he accused Whipple of selecting as her central example “a life defeated by polygamy,” which “leaves a bitter, angry distaste for the system.” He wrote, “That is unfair,” and asserted there were fewer unhappy marriages under Mormon polygamy than under monogamy. He went on to talk about what he called “the evident striving for the lurid” (which may actually have gained Whipple some readers); he claimed this “obscures the true spirit of Mormonism, and misleads the reader.”

I think Elder Widstoe is essentially right about Whipple’s unfair treatment of polygamy and her inclination toward the lurid. And I can in good conscience excuse us Utah Mormons–the readership who failed to materialize for Whipple–as probably no more guilty than any other people of honoring our dead writers and stoning the living ones. Our rather unusual history of severe persecution for our beliefs and severe hardship and suffering in leaving Nauvoo and planting a civilization in the desert–our costly struggles with the powers both of intractable earth and devilish men–give us an extra burden of defensiveness, special difficulty in responding to literature that deals honestly, and therefore somewhat critically, with our religion and our history.

But I can’t feel good about what happened to Whipple. Someone, apparently Elder Levi Edgar Young, who was then President of the New England States Mission and was asked to review the book for the publisher, convinced Houghton Mifflin to reduce the press-run because it was anti-Mormon and would not sell in Utah. (According to Whipple, Houghton Mifflin originally planned on a big Utah sale–and even thought Joshua might be made required reading for all Mormons, it was so sympathetic!) I qualify all of this because, having yet found no independent verification, I have only Whipple’s word (although Clinton Larson tells me he was present as a young missionary in the mission office in the fall of 1940 when Elder Young was reading the page proofs and pronounced the book a damned lie). The only real fact we have is that Whipple developed, as a result of something that happened to her, a crippling paranoia, a persistent bitterness about her experience, and did not complete any more novels, or many more Mormon stories. And some kind of attention must be paid to that as well, by anyone who cares about Mormon literature–especially perhaps by anyone like me who agrees with the substance of Elder Widtsoe’s critique. At least I can’t help feeling a haunting, unfocused guilt–a feeling of responsibility which I try to discharge by being a friend to Maurine, and by trying, as I am now, to pay honest, appreciative attention to her achievement. The reality remains that we do have Joshua and that now many more (including a whole new generation) can read a work which, despite its flaws, remains probably the very finest piece of fiction about Mormon history.

Part 1 Notes

[1] Ray B. West, Jr., Writing in the Rocky Mountains (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1947), 34.

[2] Laurel Ulrich, “Fictional Sisters,” in Claudia L. Bushman, ed., Mormon Sisters: Women in Early Utah (Cambridge, Mass.: Emmeline Press, Ltd., 1976), 254.

[3] M. W. S., The Christian Science Monitor, 1 February 1941, 10.

[4] E. H. Walton, The New York Times, 12 January 1941, 6.

[5] Ray B. West, Jr., The Saturday Review of Literature, 23, no. 1 (January 4, 1941): 5.

[6] “Maurine Whipple’s Story of The Giant Joshua,” as told to Mayrruth Bracy and Linda Lambert, Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon thought 6, nos. 3&4 (Autumn-Winter 1971):56.

[7] John A. Widtsoe, The Improvement Era 44, no. 2 (February 1941): 93.

Part 2

The narrative tells the history of the colonization of that area in southwest Utah called “Dixie,” which Brigham Young directed, beginning in 1861, in order to provide various products for the Mormons in his self-sufficiency program, especially the cotton which the Civil War made unavailable. A major focus in the settlement story–and a skillfully developed central plot line–is the struggle with a terribly alien land, especially the struggle to control for irrigation the Virgin River, with its sudden catastrophic floods. After twenty-five years of losing progressively larger and more costly dams–as well as their crops and even lives–the settlers harness the Virgin with a diversion damn and spillway system that I know Whipple believes was divinely inspired.

This central drama of pioneering–so central that some think the land is the novel’s true protagonist–is handled extremely well, with unique richness of historical detail, partly because of Whipple’s unmixed pride in the achievement of this victory of her ancestors over their natural, non-human antagonist. The defensiveness that Dixieites have always felt because of snobbery and even unChristian treatment by their more fortunate northern brethren and which Whipple felt personally when her own work was met with “What good can come from St. George?” is baptized in a saving, though poignant, humor–partly through the use of ready-made folklore and native poetry.

Actually, the real protagonist is, of course, Clorinda MacIntyre, a marvelous creation of a woman. Clory is from a wealthy Philadelphia family, and her mother occasionally sends her luxurious objects which are totally out of keeping with her practical needs but which serve as important symbols of her rebellious yearnings and of her sense of the legacy she wants to build for her children, a hope that sustains her through her great sacrifices. One of these gifts, a paisley shawl, becomes the shroud for her daughter, when all three of her children are taken by Black Canker; another, a rosewood desk which she imagined her children sitting at in civilized comfort, ends up in a museum. Such a fate for Clory and her dreams was determined when her father, while she was still an infant, left her mother to join the Mormons and then lost his life crossing the plains. The man who had converted her father, Abijah MacIntyre, raised Clory and then, when she was only seventeen and falling in love with a young Gentile soldier, took her, at Brigham Young’s direction, as his third wife and as part of the colonizing mission to Dixie.

We first see Clory on the last leg of the late winter journey to the site of St. George, and we are quickly and skillfully made to experience through her senses the hostile landscape and the details of Mormon pioneering: the building of a dugway, interrupted by a childbirth, the healing through anointing with oil of a crucially needed ox. We also quickly begin to see her as a complex, delightful, exasperating human being, whom we come to care about deeply and whose extraordinary burdens we feel with great pain. Clory responds to the landscape, which is “white and crimson, or black and yellow and blue, spewed in fantastic violence . . . unreal . . . glittering with such intensity that she closed her eyes . . . A regular crazy quilt of a country; savage, repellant, challenging, wildly beautiful,” [8] and it is clear she both fears it and is kindred to it. She brings life to a weary caravan with her singing and finds a rare harmony with Abijah, the man she had grown up thinking of as an uncle, through their singing together. She flirts, at first innocently, with that man’s son by his first wife; he is a boy nearly her own age whose name, Freeborn, becomes increasingly ironic as he is imprisoned in a hopeless love and the resulting conflict with his father, finally destroyed essentially by the conditions of his birth.

Clory is charming, vivid, intelligent, spunky, in ways I imagine Maurine Whipple was as a young woman–and still is behind the bitterness. Her first sexual experience with Abijah, with his annoying “Hawcck” and repellant grinding of his teeth in his passion, is rather explicit, revolting–in fact, in Elder Widtsoe’s words, “lurid.” Clory turns away bitterly, realizing she would never think of him as Uncle again. But Whipple shows Clory, not long after this first experience, as Abijah spends his allotted week with her and then stays on, in a continuing passion, succumbing to “breathless fluttering and mute terrors,” an awakened sexuality that she can’t talk about but enjoys. Whipple reveals a significant ambivalence as she shows her heroine in various ways enslaved by her passions and their results–using her sexual attractiveness as a tool to get what she wants, even as a weapon to hurt Abijah. We see Clory change, as any male chauvinist would predict, when she has a baby, revelling in the life that courses through her as she nurses it, seeing with new wisdom through the child’s eyes, for a time at least turning from her love of Freeborn and “the alarms and qualms of girlhood” that now seem foolish. But before long we see that spunk again; she again longs to batter life to gain her desires and wants the plain, gentle second wife, Willie, to battle too. It is Willie who tells her, “It’s harder for you to be brave, because you’ve got so much imagination.” And she does: She constantly tries to stretch the physical and spiritual walls that crowd her; she builds her own dugout home and furnishes it with those few things she has saved to leave to her children; she plants the highly incensed Italian shrub, bergamot, in her doorway to use for a unique perfume that Whipple makes into a fine symbol. She takes organ lessons at great cost and learns the arduous process of making buckskin gloves to pay for the price of imagination.

We perhaps see Whipple’s most stark identification with Clory when she is shown listening to a friend’s husband and a visiting Gentile, who are “discussing the state of the universe, wrangling over religion, debating dogma . . . Clory listened and listened. Hunger for knowledge can be as real as hunger for meat. Hunger for knowledge and dreams of far places and shining cities” (363). But the hunger is never really met, the dreams realized, despite even some spunky preparations and efforts by her to leave St. George. And it finally appears that the great antagonist is not really the land, but polygamy. In a horrifying, powerfully symbolic scene toward the novel’s end, during the Great Polygamy Raid of the late 1880s, Clory hides under a bed in friend’s house while federal officers who are prosecuting polygamists (The Deps) taunt a woman in labor with obscenities: “‘I can’t stand it,” she cried with all of her being, ‘I can’t stand it.’. . . No longer was she strong, mistress of her life and her own soul. Sometimes polygamy seemed more than a condition, it was a Thing and she had thrown herself against it and been bruised” (580-81).

Indeed it is polygamy, the creation of blind and unfeeling men, including a male God, in Clory’s view–and I think Whipple’s, that destroys her life. The loneliness and emotional struggle, from sharing Abijah with two others, and the added physical struggles when she doesn’t have him much at all under the polygamy persecutions, leave her at forty, losing her beauty and health, plagued by repeated miscarriages despite medical advice she should no longer bear children. Then Abijah marries a young flirt, “a pert minx with bold, big-boned bustle,” to take as his one allowed wife under new Church policy, when he leaves to be President of the Logan Temple. When he leaves Clory is again pregnant, from a period of renewed passion where she tried to win back his love so he would take her with him, and after a horrible miscarriage in the street–“lurid” again–she dies. But it is a lingering death in which she has time to come finally to what Whipple has her call a testimony, a mystical sense of a Great Smile beckoning among a thousand exploding light-balls and a vision of the Joshua trees of the title, pointing toward her Promised Land.

The Giant Joshua Tree of California is also used as an effective symbol, beginning with the telling, early in the novel, of how the Saints, returning from the San Bernardino colony in 1857 for the Utah War, had seen these huge desert trees with their outstretched arms as like Joshua pointing the Israelites toward the promised land. They become for Clory and Free an image pointing outward–a symbol of the freedom and fulfillment of desire they imagine lies outside the confines of St. George, Mormonism, and polygamy. But Clory, in telling her children the meaning of the trees, is true to the original myth–the arms pointing toward Utah and the Mormon community. At the end the symbol has lost any definiteness of direction as it merges into the disturbing mystic irresolution of the novel’s conclusion.

That ending, and the religious and artistic difficulties that it entails, are the major fault of the novel. The other flaws are, I think, quite minor. There is perhaps too vivid dwelling on suffering and on the sexual complexities of polygamy. There are some historical mistakes, like having “fast day” on the first Sunday instead of Thursday as it was then, referring to the Mormons practicing polygamy at the time of the Haun’s Mill Massacre in 1839, and the implication that the Church approved Abijah’s desertion of his first wives when he took a new young one to Logan as temple president. There are also occasional false notes of dialogue or interior monologue, some undigested exposition of Mormon doctrine or history or folklore, seams in the fabric of reality, the believable new world that it is the novelist’s gift and task to create for us. But Whipple does create that world with brilliant vividness and freshness, humor and believability.

Ray B. West once wrote that the American novel–and especially the Western novel–has not been characterized by excellence of style or compactness of design, but has been known for “a native vigor, a robust and almost reckless kind of energy” and criticized for a consequent “roughness.” [9] And the critic and novelist George P. Elliot has pointed out that “the novel is odd in this: great representatives of the form are impure and imperfect.” [10] Joshua, though not in company with the great ones Elliot cites like War and Peace and Huckleberry Finn, is similarly strengthened by not being pure in form, by being alloyed with folklore and vernacular poetry, history and doctrine, by audacious changes in point of view as Whipple breaks from Clory as the central consciousness to the mind of Erastus Snow or Brigham Young or even to the whole world itself personified–even moving a few times into her own undisguised voice in the present.

But it is Whipple’s own point of view that poses the problems of the last part of the novel–the major flaws I mentioned. Though I think Whipple is, next to Virginia Sorensen, the best of the Mormon regionalist writers, and is able at times to transcend their perspective and limitations, she finally remains, to quote Sorensen’s own description of those writers, including herself, “incapable of severe orthodoxies . . . striving to somehow balance the importance of the individual (the writer’s respected and ancient concern) with the importance of the great events that weld people into vast groups and crowds into anonymous armies.” [11] Clory, with whom Whipple deeply identifies, is like the protagonists of Sorensen and the other “lost generation” novelists, also “in the middle,” caught between the instinct for freedom and the demands of loyalty and obedience. Geary, the most thorough critic of these writers, notes that “With the ambivalence which is almost the hallmark of Mormon regional fiction, Clory resists the demands of the community and yet finally dies in harness, abandoned by those she would not abandon.” [12] But that conflict is not the problem; great fiction of course depends on conflict. The problem is that Whipple created an epic, deeply-moving frame for that conflict, carried it powerfully toward a climax and then–through some failure of knowledge or faith, some lack of tough-mindedness, perhaps merely a deep-seated anger at males and authority–could not hold true to her vision of the paradox of public duty and private inclination, of integrity both to group and to self, through which we must work out our salvation in fear and trembling. As a result, for many the novel seems to dissolve in rancor, sentimental mysticism, and melodrama.

Mormon writers have tended to have either the community vision of the zealot insider, as we find in what might be called the first or pioneer generation and the second, “home literature,” writers, or else they have had the individualistic, critical insights of the sometimes sympathetic but nevertheless detached outsider, the third or “lost” generation Geary has examined. The first and second groups were provincially inward-looking; the latter group might be called provincials precisely because of their self-conscious rejection of provinciality, their outward-looking unwillingness to give themselves wholly to understanding their own people and place.

Whipple came closest to combining these two valuable sets of insights. But finally, it seems to me, she failed to fulfill her promise. She let youthful inexperience and immaturity, focussed in her bitterness toward Abijah and polygamy, destroy the ending of Joshua; then she let her bitterness about the Church’s reaction to her book keep her from finishing the trilogy, where she might have worked out the problems of Joshua and given us the great Mormon novel.

Richard Blackmur has said that tradition, or a traditional system (which is certainly one of the advantages Mormon culture provides its writers), “can become a satisfactory objective symbol for the expression of human emotions only when that tradition is decadent, when it becomes something more than an exacting guide for living, then the artist is free to use those materials as an objective correlative.” [13] If you will allow me a slightly different definition of decadent than Blackmur may have intended, I think him right. The advantage of Mormon writers have, of a usable past, what Ray West has called “an institutionalized cultural core which provided a preconceived attitude, a scale against which personal experience could be evaluated” [14]–this advantage is lost I think when the writer’s own ignorance or ambivalence or pride or whatever let him either be enslaved to the past as a continuing code or turn against it in anger or bitterness. Wallace Stegner has said of Western writers–and it seems true of Mormon’s lost generation including Whipple, “We cannot find, apparently, a present and living society that is truly ours and that contains the materials of a deep commitment.” [15] I believe the great Mormon novel will be written by someone at peace with the Mormon past and at home in its present–yet someone who retains both the critical objectivity and the artistic flexibility to mold the raw materials of the Mormon tradition, while holding true to their essence, and thus reveal a unique esthetic perception of human acts and motives. She, or he, will have a balanced sense of both individual and community integrity, will have 20 x 20 vision in both the eye of faith and the eye of knowledge, will see the faults without rancor or self-righteous pride and the virtues without sentimentality or self-consciousness. The writer of the great Mormon novel will be someone whose conscience remains sensitive and courageous but whose wounds have healed. Maurine Whipple was not quite that person; the tragedy is that with some help, not so much the material kind she now sentimentally thinks she most needed, but serious encouragement, loving criticism, she perhaps might have been that someone. [16]

Part 2 Notes

[8] Maurine Whipple, The Giant Joshua (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1941; rpt. Salt Lake City: Western Epics, 1976), 3. Subsequent references are in parentheses in the text.

[9] Writing in the Rocky Mountains, 25.

[10] George P. Elliott, Conversions: Literature and the Modernist Vocation (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1971), 95.

[11] “Is It True?–The Novelist and His Materials,” Western Humanities Review 7 (1952): 182.

[12] “The Poetics of Provincialism: Mormon Regional Fiction,” Dialogue 11 (Summer 1978): 15. See also, on this group of writers, Geary’s “Mormondom’s Lost Generation: The Novelists of the 1940s,” Brigham Young University Studies 18 (Fall 1977): 89-98.

[13] Quoted by West in Writing in the Rocky Mountains, 74.

[14] Ibid., 75.

[15] The Sound of Mountain Water (Garden City, N. Y.: Doubleday, 1969), 178.

[16] For a suggested Mormon literary history, including an analysis of three separate generations of good writers and some evidence that the third is beginning to achieve the balance and quality I suggest might produce “the great Mormon novel,” and already has to its credit many other fine literary achievements, see my “‘The Dawning of a Brighter Day’: Mormon Literature after 150 Years,” in Thomas G. Alexander and Jessie L. Embry, eds., After 150 Years: The Latter-day Saints in Sesquicentennial Perspective (Provo, Utah: Charles Redd Center for Western Studies, 1983), 97-146 (with select bibliography of Mormon literature).

Part 3

I turn to the novel now, to see if there is evidence for my generalizations. The first hints of the problem come with the passages describing Clory’s religious experiences. Ulrich is right in noting that Whipple is to be commended for making Clory one of the very few romantic heroines in Mormon novels who has religious experiences, but that even so these are awkwardly rendered: “Whenever things get too bad for her, she turns to a kind of kindergarten mysticism, dwelling on thoughts of ‘The Unopened Door’ and ‘The Great Smile’ (which has a way of turning into Charlie Brown’s ‘Great Pumpkin’ once the spell of the book is broken).” [17] For me these resounding abstractions (Whipple always helps the reader know what’s happening by capitalizing them), these vague and unsatisfactory mental Solutions to Clory’s problems turn into Emerson’s Oversoul or Transparent Eyeball.

And it is quite possible that Whipple’s destructive confusion came not only from a lack of thorough knowledge of genuine Mormon theology but from having been uncritically exposed to Emersonian Pantheism, perhaps in her general reading or the general climate of l930s liberalism, perhaps, an ultimate irony, from some Mormon Sunday School teacher or even Authority who, like some today, quote Emerson without considering what pious heresy is thus being distilled into innocent ears.

Without more solid underpinnings in a secure knowledge–in an informed testimony–of Mormon thought, Whipple finds herself toward the end of the novel with two developing explanations for the epic and tragic story of the pioneers she is telling: On the one hand she creates a marvelously-realized emotional sense of their gritty faith and genuine religious experience, and on the other she indulges in imagining for them humanistic and pantheistic perceptions that are closest to her own. She tries to have it both ways, in the last scene having Clory recognize the Great Smile at last: “That which she had searched for all her life had been right there in her heart all the time. She . . . had a testimony” (633). But as my students always point out, “That isn’t a Mormon testimony!” and the reader tends to feel Clory has lapsed into a kind of religious insanity, that a tragic and heroic life is ending trivially–especially when her next, and last recorded, notion is to ask her son to “see that my fingernails look nice. Sometimes the women neglect fingernails.”

It is that trivializing that most disturbs me, that is most destructive to the novel. It begins in Whipple’s unresolved rancor about polygamy and the male chauvinism that produced it, begins to express itself in revenge upon those males involved, especially Abijah, but finally leads to a loss of control that trivializes the plot through melodrama and even undermines the protagonist, Clory. Clory is torn constantly. On the one hand is the genuine and heroic faith of Abijah’s second wife, Willie, who even just after losing her first child because of neglect by the first wife, Sheba, still has a “serenity Clory had come to trust, that look of peace and infinite wisdom, still lived behind the grief.” On the other hand is Clory’s growing sense that “as the old world turned she was conscious only of a bad taste in her mouth. A nameless longing . . . polygamy was a prison with bars stronger than iron” (180).

A great strength of the novel is Whipple’s effectiveness through most of it in showing in convincing detail the reality both of Willie’s kind of faith and of the prison of polygamy.The novel declines when the author’s resentment takes over and she focuses solely and self-indulgently on the horrors of polygamy. She first takes revenge on Abijah. Though men have, from the first reviewers, found him so uncongenial as to be unconvincing, he is, as Geary has suggested, up to a point quite a good portrait of a man who lacks self-knowledge. His self-righteousness and male chauvinism are certainly believable and not merely one-dimensional. Whipple writes of him, “Thwarted at the beam in his own eye, he plucked at the mote in his neighbor’s.” His helplessness in the face of Oedipal conflicts that he does not understand and will not learn to be patient about lead to self-defeating efforts with Free and then with Clory’s son Jimmy, vicious circles of inarticulate love, thoughtless neglect, and then physical punishment when the boys act out–a cycle that we can all understand and share his pain about.

We can even forgive Abijah’s incredible cruelty in writing Clory from the mission field in England that the death of their three children is God’s punishment on her. We can because he later admits his wrong and especially because Clory forgives him. One of the dynamics of dramatic fiction is that characters accrue their virtues and their credibility in part from the assessments of them by others we trust. When Abijah anoints and heals the ox and thus saves a woman in childbirth, Clory “suddenly . . . shared [a] childlike belief in Abijah; it came to her that Abijah was in many ways a great man. He was ruthless, fanatical, bigoted–a man more capable of winning respect than affection–but a man to be depended on when you needed him” (47).

Our respect grows with Clory’s own, and when her affection for him develops ours does too. Listen to Whipple’s description, from Clory’s point of view, of Abijah blessing their unconscious daughter Kissy after a wagon has turned over on her:

Abijah was like a madman. “Help me, Mother,” he said, holding the child up, putting his ear against her chest, fanning her face. Not until after did Clory remember he had called her “Mother.” “I haven’t any oil,” he said, “but–” He had always prayed as if God were there beside him, but now placing his hands upon Kissy’s head, he pleaded with such desperate eloquence that Clory leaned to kiss the horny knuckles. At that moment, with the blood of his wound, the dust of the accident, the sweat of his terror still upon him, stripping him of overlaid emotions, stripping him to the core, she loved him. All her life there would be instants, lost in memory, when the authentic passion for Free returned. . . . But she could live with Abijah. She knew it now. She saw beneath the shell, and with what she saw, she could fashion a life. (386-87)

Whipple is untrue to this man she has created, or to Clory’s influential appraisal of him, when she turns him into a grotesque old fool at the end–and in the process she begins to turn Clory herself in to a grotesque and to damage the quality of her own writing.

For instance Whipple combines the useful and believable theme of puritanic male chauvinism with what I can only see as her own ambivalence about sex and then carries it to unbelievable extremes as Clory tries to literally seduce Abijah into taking her with him to Logan:

Now in her thirties she had taken on a second blooming that left Abijah, trying to make his nights with her dull fulfillments of duty, weak-kneed with passion and torn with a thousand remembered intimacies. To pacify his conscience he reverted to the old resentment against her attraction for him, telling himself that her eternal feminine sorcery was really what stood between his soul and God, rather than his own nature. (539)

That is right out of the middle ages, the impulse and theological justification that led to the murder of hundreds of thousands of “witches,” but Clory is there in the middle ages with Abijah: “She wheedled him, coaxed at the abysmal, innate sweetness she loved and that he could never quite hide” (541). That word “abysmal” is a dead give away, a Freudian slip by Whipple that reveals a corrupted view of sex and of character that continues to grow until we see Clory on her deathbed, able to laugh at the news that Abijah’s young bride he took to Logan has had a miscarriage.

Such moral corruption inevitably corrupts the style, which becomes increasingly breathless and uncertain, and even the plot, which has sustained for much of its first 500 pages the painful logic and disciplined leanness of fine historical tragedy, but at the end falls off into sheer melodrama. Clory and Sheba descend on Abijah, as he sits in a neighbor’s house with a fatuous grin on his face and on his lap the young flirt he is courting, “being very kittenish stroking his beard” (604). Clory and Sheba, finally united, and the two wives of that household, including the girl’s mother, plead against the match, and some hope is raised that the girl’s father might be able to dissuade Abijah. But he is away hiding from the Deps. But then again Clory looks out the window to see him coming just in the nick of time. But wait, now he falls, shot down in cold blood by the waiting Deps as he plunges out of the brush–and his death only serves to tie Abijah more strongly to the young flirt because of his pity for her grief.

Finally all thematic and stylistic restraint is lost. Whipple has Clory get involved in temple work for consolation and then, when she meets there a sterile and unctuous old polygamist who has also taken a young wife, she abruptly flees in terror, “ran all the way home, and even in the stifling dusk, banged the door tight against all the nameless horrors of widowhood.” Whipple even has Erastus Snow, the sensitive, humane and devoted Apostle who has been one of her finest creations, undercut himself by lapsing into a vague mysticism akin to Clory’s. Snow, who has maintained throughout the closest thing to intelligent faith, an understanding both of individual need and group necessity, is pictured as equivocating about what testimony is–perhaps, he says, an Idea: “Thou Shalt Love Thy Neighbor” (507).

Part 3 Notes

[17] Laurel Ulrich, “Fictional Sisters,” in Claudia L. Bushman, ed., Mormon Sisters (Cambridge, Mass.: Emmeline Press, Ltd., 1976), 75.

Part 4

Actually, though that “idea” of loving your neighbor isn’t exactly the unique core of Mormon theology and the main motivating basis for Mormon commitment, it really isn’t a bad idea. And one of Whipple’s fine achievements is in conveying a sense of how central that Idea of neighborly love really was to the Mormon endeavor. There are many other achievements as well.

Even that ending could be argued about, of course. Time‘s review for instance, found that “only in the last 30 pages does the novel approach its promise, providing a strong groundswell almost to the edge of grandeur.” The critic Robert Scholes, in an essay about four Midwestern “frontier” novels, focussed on the abiding final image in each in a way that suggests a more positive perspective that could be taken of Whipple’s conclusion. In his essay, Scholes analyzes the flawed pioneer vision, the exploitive “prairie consciousness,” that the original Lutheran settlers of the Midwest indulged in and which, through morally ruinous to their subsequent societies, provided a base for fine literature in the skillful criticism and satires of Ole Rolvaag, Sinclair Lewis, Willa Cather, and William Gass. In each novel Scholes discusses it turns out that at or near the end the protagonist is presented looking in a direction and with a perspective that epitomizes the central concerns of the novel, which Scholes sees as being the failure of that heroic but tragically flawed pioneer vision.

At the end of Giants in the Earth, the protagonist, Per Hansa, has perished in a blizzard after somewhat guiltily succumbing to his wife Beret’s irrational insistence that he seek help for a dying minister; he is shown sitting against a haystack, staring with dead, sightless eyes into the West, that immense frontier that he had wrongly thought infinite and infinitely exploitable and a direction that represents both the driving hope of his kind and a future that will indeed be dead for his children. In Main Street, Carol Kennicott, a diminished version of Beret whose own rebellion against the materialistic and benighted preoccupations of those around her is smaller and even more futile, also looks West in the final scene; she is not sitting on the earth like Per Hansa but riding in a car like any other woman of Main Street, and she looks out on the West sweeping across fields to the Rockies and Alaska in hopes that out there will be a “dominion which will rise to unexampled greatness”–but that she realizes will come only after “a hundred generations of Carols will aspire and go down in tragedy . . . the humdrum inevitable tragedy of struggle against inertia.” And rather than Beret’s genuine if excessive and crazed spiritual vision that Rolvaag thrusts against the lust for exploitation, Carol can only offer the “civilized” values of the great cities of Europe, which Sinclair Lewis himself could not see the thinness and shallowness of. Lewis apparently forgot what Beret, and certainly the Mormon pioneers, knew–that they had left those decadent cities, built on exploitation not of mere land but of human beings, for very good reasons.

Similar images of ironic futility occur at the end of Cather’s My Antonia and Gass’s In the Heart of the Heart of the Country. But the final image in Joshua is tellingly different: The protagonist is dying following a miscarriage, having suffered incredible extremes of physical, emotional, and spiritual pain. However, different from the protagonists or narrators of the novels Scholes discusses, Clory is surrounded by the sacrificial help and love of a successful community which never lusted toward the West; and she looks upward, not Westward, and comes to a special realization of her fundamental faith:

Sometimes she sang, little catches of the songs that had defied a wilderness. “Come, come, ye Saints . . . ” Singing as if she wrote in her heart’s blood her own wistful cadenza, singing as if to seal with her blood the final resolving chords. (631)

Despite my grave misgivings about the thematic and characterization weakness in that ending, it does, in terms of Scholes’s analysis or moral perspective, have a certain symbolic rightness. And Whipple is remarkably true throughout to those crucial elements of Mormon pioneer vision that make it different from the Mid-western one Scholes found so flawed. She shows, honestly and movingly, the building, under prophetic direction and against private inclination, of communities with the aid and challenge of the Law of Consecration and of families with the aid and challenge of polygamy. Despite her realistic revelation of their failings and failure, Whipple puts the arguments for both the United Order and polygamy in the mouths of sympathetic, convincing characters. And undergirding all she shows the search for effective group religious life and individual redemption. The following passage gets at the heart of the struggle and achievement, as Erastus Snow meditates on the first year under the United Order:

That Christmas . . . Erastus surveyed his community and was not ashamed to uphold its accomplishments even to Brigham, whose face these days seemed more than ever like parchment, whose eyes could not hide their longing for proof that this work of his lifetime would stand.

“Enoch hats, a half-finished Temple, brush grubbed from the sidewalks and the square,” inventoried Erastus, “and above all, something you can’t see but is worth much more to a man–a sense of responsibility toward his neighbor, an armor against selfishness and greed. . . .” (520)

The central (and I believe true and in modern times unique) religious vision that makes The Giant Joshua live in our minds and hearts is the central Mormon one. However much that vision may have failed in former times, or is forgotten today, Mormonism is committed to an egalitarian communal ideal in which all of life–including the social order–is integrated together and motivated by religious faith and love rather than economic sanction, in which life is not divided between sacred and secular. Whipple builds and reveals in detail that vision, with remarkable skill, right up to the end. One effective device she uses is showing a well-educated, articulate, visiting Gentile in conversation gradually coming to express the Mormon vision for them all: “‘Togetherness.’ His voice was very soft. ‘You were persecuted because you had togetherness, but it also gave you your strength'” (364).

Whipple is even able to capture, with remarkable intuition, perceptions about the Mormon colonization and its guiding vision and leadership that historians have just recently been coming around to. For instance, Brigham Young once said that the immigrants coming to Utah from Europe and the East, the people he sent out to colonize places like Cache Valley and Parowan and Whipple’s St. George, were “like clay on a potter’s wheel,” people who “have got to be ground over and worked on the table until they are made perfectly pliable, and in readiness to be put on the wheel, to be turned into vessels of honor. [18] Whipple, through the eyes and voice of her creation of Brigham Young and of Erastus Snow, gives the clearest and one of the earliest expressions of that central idea that the colonists were created basically as good places to make the Saints, that the terrible physical trials would be in the main a help, and that the truly destructive trials would be the trial by riches–and the people who came as a natural consequence of riches, the Gentiles. And Whipple’s artistic intuition leads her naturally to what only one Mormon historian, Charles Peterson, and only recently, has begun to articulate–that the Church leaders fought a rear-guard action against the Federal government and the Gentiles that delayed accommodation for two decades and allowed them to continue their colonizing process into isolated rural communities, particularly in southern Utah. Thus through a creative withdrawal Mormon peculiarity peaked in the Mormon village and the conscious rejection of mainstream American institutions and values, to which the flight into the desert in 1847 first gave maximum expression, was re-enacted and protected for many decades, and most of the towns were preserved in their essential nature until about 1940. This is the imagined Erastus Snow:

“I remember in ’47, Sam Brannan fresh from California’s sunshine and flowers, saying to Brigham Young, ‘For heaven’s sake, don’t stop in this God-forsaken land. Nobody on earth wants it!’ And Brother Brigham answering him, ‘Brannan, if there is a place on this earth that nobody else wants, that’s the place I am hunting for.’ . . . Well, folks, only the lizards want Dixie. But think what that means! . . . We’ve got tested men here, handpicked for endurance, to wrest out of hell a cotton supply. But we’ll wrest out of hell a great deal more. . . Long after the gentiles have invaded the North, they’ll let us alone . . . Forever alone, folks, to tame the lizards, to sink roots we’ll never have to tear back up, to build the Land-of-the-Unlocked-Door.” (91)

I only wish that Whipple could have seen, though even Charles Peterson doesn’t see it, that Brigham Young’s success in perpetuating in the Mormon village that essential program for making Saints–a self-governing community, cooperative irrigated farming, practices of resources utilization based upon stewardship and the public good rather than speculation and competition, and an economy of cooperating self-sufficiency–that she could have seen not only how these were preserved through the pioneering phase in villages like St. George but how the ideal lives on in the hearts and expectations of faithful Mormons, fostered by the ideals of leaders and artists raised in these times and by a number of concrete religious experiences in their congregations, even while they engage quite fully in the American economic institutions that were once seen as a threat. But perhaps that would have been hard to see in St. George in the 30s; perhaps the cultural breakdown in the towns–the post-isolation malaise, materialism, and loss of the familiar forms of the ideal–was too difficult to see beyond and Whipple was left, like the rest of the lost generation, only able to celebrate a more heroic age and lament its passing.

And there are many things that Whipple did see more clearly than nearly anyone. Brigham Young, for instance, is created with a combination of humanity and prophetic power that leaves me in awe. I worked two years writing a book on Brigham Young, with sources that include many which could not have been available to Whipple, and have become convinced of things about him that contradict the preconceptions of myself–and of many others–from antagonistic gentile biographers to Mormon historians to General Authorities. And on rereading Giant Joshua I find her not only intuitively dead center on his qualities but able to give them marvelous imaginative life. There are some strained set pieces which Whipple has taken too obviously form Widstoe’s edition of Brigham Young’s Discourses, but in general the speeches and conversation and action are convincing and captivating.

We see Brigham first in the admiration and love of people we have come to respect, who talk of him and wait all day in the sun for the first glimpse of him; we hear his speech, pungent, practical, moving. We see him invite the ladies to come to the welcoming dance in homespun, at the dance asking that all that participate be pure in heart, see his wife Emmeline Free Young arrive in States’ goods and hear Sheba’s comment, “Even a prophet o’ God can’t boss some women,” and then see Brigham’s joy in his own correct and lively dancing, his feet “like two crickets.” We see his intense interest in every detail of his people’s life as he visits and advises Sheba while she is soap-making and strikes at her hidden depths of selfishness by suggesting she share the soap with her neighbors at the same time that he compliments her on it. He goes down into Clory’s dugout to advise her to use soft flannel instead of rough cloth on her baby and gives the child a blessing.

Whipple draws back to her narrator’s voice for general impressions of Brigham that ring true to what she has shown us: “There was none more steadfast than Brigham, none in whom success had developed so little of pride and vainglory” (212). She describes “the strength, the human kindliness that emanated from his compact body” (217). Again, part of our feeling for Brigham accrues from the credit Whipple gains from our feeling from Clory, who in turn loves and admires Brigham, but it is a credit fully justified by what I have been able to find out about him:

How she worshipped him! She had gone into the Endowment House that day ready to “spit on his robes,” but she had come out ready to walk over coals of fire for him. He had said, “I am now almost daily sealing young girls to men of age and experience. Love your duties sisters. What is your duty? It is for you to bear children, in the name of the Lord, that are full of faith and the power of God–that you may have the honor of being the mothers of kings, princes, potentates–I would not care whether my husband loved me or not, but I would cry out, like one of old, in the joy of my heart, ‘I have got a man from the Lord! Hallelujah! I am a mother–I have borne an image of God.'”

Well, she had “loved her duty”; but she was sure he had no idea what a cross he had given her to bear. Yet even now, she would gladly have married ten more Abijahs to win his word of praise. (249-250)

There are many other things that Whipple knew and knew how to say well. Perhaps most surprising, given her tendency toward romantic mysticism and her poor reception among her own people, is her ability to capture the unique spirit of Mormon devotion and what Lavina Anderson has called “spiritual realism,” the author’s unself-conscious witness to the direct presence of spiritual experience within the realities of physical human life. A prime example is Willie, dying painfully after the birth of her child, telling Clory the secret, kept hidden through most of the novel, of her strange withdrawal from life, especially from the often superficial religious gossip of the women around her:

Bit by bit during those long night reaches, the story of Willie’s past came out, that past so dreadful that she had kept it hidden all her life. And bathing her pain-wracked limbs Clory saw deep, embedded scars along her elbows, her knees, the bottoms of her feet. And in an anguish of contrition Clory understood that queer hobble, like a jointed mechanized doll.

” . . . So happy,” muttered Willie, her eyes staring vacantly at the ceiling, “Joe and me and the two kids on the ocean. ‘Ow good the chicken bones tasted after the sailors had thrown them away! . . . They said it was too late to start but the men was anxious. And we women didn’t know nothin’ except we ‘ad to push them ‘eavy carts a thousand miles.”

. . . . “I remember one elder says we should trust in common sense as well as the Lord. . . .”

Greasing axles with bacon and even soap. Chewing a crumb of buffalo meat until it got white and tasteless. Rationed to less than half a pound of four a day. Feet festered, wrapped in rags. Remnants of human bodies eaten by wolves. Five hundred head of cattle stiff amid the snowbanks. Tents and wagontops blown away and wagons buried up to the tops of the wheels. Men pulling their handcarts up to the moment they died. Wading a river and cutting shins against the block of ice. Joe eating a dead horse in the moonlight, mistaken for a wild animal, shot. Ground too frozen to dig graves. Sixteen die in one night, bodies piled up. Not enough men with sufficient strength to pitch tents. Sat on a rock until morning with dying children on my lap. Feet frozen, bare upon the snow, I crawled forward on hands and knees, then on elbows and knees. . . .

. . . . “I’m sorry to ‘ave such a ‘ard time dyin’ . . . Don’t let ‘Sheba lay me h’out. I’ll be just another dead body to ‘Sheba!”

And then when Clory had promised, and the pale eyes had lost their look of desperation:

“A voice, not a whisper, but still and low said to me: ‘If you will leave your ‘ome, father and mother, you shall have Eternal Life.’ I ‘ave heard the same voice since, not in dreams but in daylight, when in trouble and uncertain which way to go; and I _know God lives_ and guides this people called Mormons. . . .”

Her eyes, already filled the mystery of the last long trek, were dark with faith.

“Don’t never knuckle under to life, Clory. Don’t never knuckle under, if you ‘ave to crawl–all–the–way!” (496-99)

There is also the marvelous creation of Tutsegabbett, the local Indian chief who becomes a Mormon. He joins the other authorities as, standing in the sun, they wait for Brigham Young’s visit, “sensible in his nakedness among the sweating broadcloth-covered bodies of the white men. This celebration seemed more like an ordeal or endurance to him, but he had cast in his lot with the Mormonies and he was trying his long-suffering best to live up to them” (231). At one point when Free’s horse is shot with a poisoned arrow during some Indian trouble, Tutsegabbett sucks out the poison and says to his beloved friend Jacob Hamblin, “We cannot be good . . . we just be Paiutes. We want you to be kind to us. It may be that some of our children be good, but we want to follow our old customs.” Later Whipple has him appear before the High Council with a complaint that makes perfectly good sense to us in the l980s but was an unusual insight for a young rural Utahn in 1939: He felt that although the horse, the rifle, and the saddle blanket he had been paid for a certain spring were long since used up, the spring was still as good as new, and he should be paid more horse, more rifle, and more saddle blanket.

But we see this interesting man first in a scene that for me shows us the full range of Whipple’s skill with plot, character, and symbol, as well as some of her flaws of sentimentality and vague humanism–but also shows her courage to create an epiphany. Clory and her friend Pal have decided to leave the community; Pal’s husband finds out, and he comes and tells Clory he’s made a bargain with his wife that if he could show her one pretty thing in all the desert she’d stay. He then takes the two young wives on horseback at dawn up over Steamboat Mountain, led by Tutsegabbett and Jacob Hamblin. The Indian tells them on the way, translated by Jacob Hamblin, the legend of Neab and Nannoo, two lovers who, with Neab’s father, have tried to stop their people from burying the sick and older Indians in caves to die. The girl becomes extremely ill and the U-ano-its tribe takes her to be put in the cave, despite Neab’s pleas:

“What you are doing is evil,” he said; “Ah-bat Moap, the great On-Top God, will take away the rain and [you] will die. You have not listened to [my father]. I go to prove his words to you. I go to intercede for you. I go to coax the anger from Ah-bat Moap.”

His people begged him to come out, but when the women rolled the boulder back into place, Neab was there to keep Nannoo Company. . . . The voice stopped. Clory was still in her dream . . . . Tutsegabbett pulled up his pony and waited for the others to catch up with him. . . . [He] spread wide his arms and Jacob matched the solemnity of his intonation.

“Ah-bat Moap, pleased with his servant, set His footprint before the cave of Neab to show his stubborn people the way.”

The Indian pony took another dainty step or two. The others followed, the girls craning their necks to peer around the figures of the men. They lined up at the very lip of a huge basin scooped out in the solid rock.

“See-coe!” cried Tutsegabbett.

Clory sucked in her breath transfixed in amazement and delight.

“David!” Pal gasped, and the two girls were on their knees among the stones of the lip.

There before them, carpeting the depression, were thousands of fairy bells with lavender hearts, tossing their lovely heads. Flowers wilting at a touch, so delicate as to be almost other-earthly there among the black rocks.

Sego lilies! Sown as thickly as a desert sky with stars. Poised like heavenly butterflies there on the grim lava surface as if they needed no roots, would float upward at a breath . . .

“. . . The U-ano-its resolved never to fight on a battlefield where sego lilies grew: thus the sego lily became an emblem of peace. . .”

Ah-bat Moap and His mighty footstep before the cave of Neab. Neab, who did not run away. (173-74)

And, of course, Clory does not run away–and also pays with her life for her devotion.

Bruce Jorgensen has compared Whipple with the remarkable group of younger American women writers whose work appeared along with hers in l94l, with similar or even less national attention: Eudora Welty, Carson Mccullers, Janet Lewis, Caroline Gordon. They each went on to a larger body of durable work and greater reputation than Whipple, and Jorgensen suggests that one of the main reasons for Whipple’s relative failure is that she did not persist in developing her strength–intuitive insight into the language, folk customs, and moral strength of her own people–and did not discipline her weaknesses–lack of understanding of Mormon spirituality and indulgence in a vague Romanticism as substitute: “A relatively ill-equipped and undiscriminating abstractionist mind undercuts the best work of a splendidly endowed folk imagination, and we can watch the struggle play itself out in passage after passage in which homely imagery gives way to ballooning cliches typical of the slick popular idiom of the thirties and forties” (8). But when she is able to remain true to her root strength, especially when she dares to attempt an epiphany grounded in genuine folk experience that she believes is true, as in the passages I have quoted above, Whipple achieves something none of those writers has. Their novels, and the ones Robert Scholes discusses by Rolvaag, Lewis, and Gass, are in many ways superior to The Giant Joshua–for instance, in stylistic consistency and uniformity of vision, in unobtrusive steadiness of characterization, in the structured power of denouement and resolution, all of which are essentially formal qualities, ones which fulfill our esthetic sense and training. But despite all this, Whipple’s novel is moving and extremely valuable, it seems to me, because it successfully conveys to our minds and hearts and a rare and challenging moral and religious vision. Her flawed masterpiece, perhaps most sadly her only completed novel, stands as a blessing and challenge to Mormon culture, perhaps especially to Mormon writers, who have yet to learn what they might from her achievement and to surpass it.

Part 4 Notes

[18] Quoted in Eugene England, Brother Brigham (Salt Lake City, Utah: Bookcraft, 1980),

WORKS CITED

England, Eugene. Brother Brigham. Salt Lake City, Utah: Bookcraft, 1980.

—. “Great Books or True Religion?” Dialogue 9 (Winter 1974): 36-49.

Geary, Edward. “The Poetics of Provincialism: Mormon Regional Fiction.” Dialogue 11 (Summer 1978):12-20.

—. “Mormondom’s Lost Generation: The Novelists of the 1940s.” BYU Studies 18 (Fall 1977): 89-98.

Jorgensen, Bruce. “Retrospection: Giant Joshua.” Sunstone 3.6 (September-October 1978):6-8.

Sorensen, Virginia. “Is It True?–The Novelist and His Materials.” Western Humanities Review 7 (1952):182.

Ulrich, Laurel. “Fictional Sisters.” In Mormon Sisters, ed. by Claudia Bushman. Cambridge, Mass.: Emmeline Press Ltd., 1976.

West, Ray B. Writing in the Rocky Mountains. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1947.

Veda Hale, who was working on Maurine’s biography in 1997, replied to England’s essay on AML-list with this post.

I think I desire to inject more of Maurine’s intention into, perhaps, the biggest criticism of the book, that she blew it in the last 100 pages.

I think many Mormons can’t understand where she is coming from here. But don’t we Mormons understand that the gospel has been here since the beginning? Don’t we accept Jesus’s words that the first and greatest commandment is to “love thy neighbor as thyself?” Well, England says it really isn’t a bad idea but that it isn’t “exactly the unique core of Mormon theology and the main motivating basis for Mormon commitment.” (page 3) Maurine thought it should be, that, indeed, it really was, but it was usually unreachable. But unreachable though it might be, the reaching was still the true fuel for human celestial-hood.

Why is it that some readers, myself included, as was the writer of that early Time review, are lifted “to the edge of granduer?” with the ending?

May I try to explain my point of view, and I’m assuming for others who liked the ending and so am going to use “we”.

First, we appreciate the little chapter before the end when that “other Clory” (her granddaughter) visits the relics of the first, because it has the effect of lifting our perspective to the high and long view. In other words, it sets the stage

and suggests we readers push the tragedy aside and look to the real message Clory is trying to hand us.

Second, we remember Willie telling Clory “Don’t never knuckle under to life, Clory. Don’t never knuckle under, if you ‘ave to crawl–all–the–way!” We take that, not as pure stubbornness, but as the admonition from someone who knows the gentle way from experience, someone who has held to the belief that life is meaningful and there is a beyond.

Third, we put the above perspective with Erastas Snow’s reverence of The Idea. We do this where he says: “Maybe, human nature being what it is, the world will always stamp upon that Idea… But you can’t kill it, Clorinda Agatha — it’s older than the world.” (620) and, though he says that he might lose, Clory might lose, Zion might lose, but “‘the Idea’–he saw

all those myriads, the oppressed and downtrodden, marching hand in hand straight into the dawn of a better world — ‘the Idea can’t lose'”, and we take heart and feel balm on our own damaged souls. (And the world outside of Mormondom did use it for this purpose. Remember this book came during and after a terrible war. It brought comfort to many people trying to come to grips with the worst horror they could imagine. Perhaps it did more real God work (missionary?) than anyone ever imagined.)

Fourth, many of us have read far outside the usual, trying to seek comfort. We read people like Paul Brunton, Mary Baker Eddy, Emerson, even Blavatsky, and the Mormon “we” pondered our own scriptures, like D&C 88: 13, 37-38 & 47 (the ALL-THINGS-ARE-BY-HIM,-AND-OF-HIM, EVEN-GOD,-FOREVER-AND-EVER scripture) and we resonated to the “All the rivers run into the sea: yet the sea is not full.” (TGJ page 632) and in our reading the last of Joshua we are pulled up to a communion with the mystic whole and rejoice.

Fifth, we have suffered and have had moments in our own lives when something indestructible and indescribable broke through for the briefest of instants, and we liked the words “The Great Smile” to attempt to handle it.

Sixth, we took the words “the land of the unlocked door” to not only mean that the land is unlocked for physical development, but that there is more than land unlocked, there is an unlocking so one might cross a threshold into richer spiritual understanding.

Seventh, and finally, we took the last words of Clory, “see that my fingernails look nice…” as not a trivial or vanity request, but as a subtle hint that Clory had won the struggle not to knuckle in to life, she had retained her self worth. No matter how desperate the circumstances, how poor her worldly goods, she could still do small things to celebrate her

“Child-of-God-ness”. She had the confirmation of that Great-Smile feeling to assure her that she did matter, that she wasn’t reaching a beaten end. It says to we, perhaps the down trodden, that it can be the same for us.

Thank you, Maurine! Thank you for your great, flawed, book! And the few of us who have the biography know that it is your very mangled, sad life and the lives of your family cut up and served, like John’s head on a platter, to a people needing a jolt to perhaps help them see beyond the “I-know-the-Church-is-true,-I-know-Joseph-Smith-was-a prophet,-I-know….” kind of testimony. No, maybe Clory’s testimony isn’t the kind most Mormons want, but it is the kind I want. I now take it to be the kind that comes after the other kind.

Veda

See also Harlow Soderborg Clark’s essay, written partially in reply to England, “She, Clory, Had a Testimony, and a Great Smile”. AML Annual, 2001, p. 69-79. https://www.associationmormonletters.org/aml-publications-documents/aml-annuals/aml-2001-annual/

Here is an excerpt:

The ending is generally disliked, even among those who think The Giant Joshua Mormondom’s best novel. I find it a good ending, and I am here to speak in contro to the versers who dislike it. The most common objection is to the penultimate paragraph . . . General objections [are]: 1. It seems too easy a resolution to a lifelong quest. It seems like deathbed repentance or a deus ex machina. 2. The vocabulary is not Mormon. As Laurel Thatcher Ulrich said in her “Fictional Sisters,” the phrase reminds one of the Great Pumpkin . . .

Testimony—especially in LDS culture—is a communal matter. We stand before our religious community and bear testimony. The metaphor is worth noting, not only because bear is the word we use for delivering a child, not only because bear is what prophets do with their burdens (songs), or what the Lord asks his disciples to do with his and each others’ burdens, but also because the word sounds like that wonderfully (or frighteningly) intimate verb, bare.

I salute Maurine Whipple’s understanding of how being rejected by a religious leader would add to Clory’s sense that she doesn’t have a testimony, and her guilt over that lack. I also salute Whipple’s ending the novel by affirming Clory’s testimony. But the affirmation is stated in terminology most Mormons wouldn’t recognize, and Whipple has been consistently faulted for not understanding Mormon spirituality. There is a deep, deep irony in this. At the end of the second to last chapter is a homecoming party for David Wright and Erastus Snow, just home from prison. Clory walks up Mount Hope—an expression of her sense, pregnant and abandoned, that she no longer belongs in the community—seeking for peace and watching the homecoming parade from that place. Apostle Snow seeks her out up there and she pours out her grief to him,

“Why, I haven’t even got a testimony” (619)

Erastus replies:

“Prison has taught me many things, Clorinda Agatha. . . . But I’ll tell you—I’m not sure what a testimony is myself.”

He laughed a little. Heresy!

“The way I look at it, the thing we’ve got that’s immortal is an Idea. And maybe that’s why we’ve been persecuted. . . . Maybe, human nature being what it is, the world will always stamp upon that Idea. . . . But you can’t kill it, Clorinda Agatha—it’s older than the world.”

His words seemed to come from out of the past, as if they had lived forever, as old as time, as old as the rocks.

“Thou shalt love thy neighbor . . . Everybody’s reaching for it, only some religions are going ‘cross-lots, some kitty-cornered. . . . None of us have yet come within a million miles of it, but the big thing is that we try. And as long as we try and admit we’re trying, there’s hope. A mosque or a pagoda or a Tabernacle . . . and maybe we’re a little closer to it in the Tabernacle because we’ve gone out for it deliberately, colonized for it. I believe that to be Zion’s mission to mankind, Clorinda Agatha—to create among these barren hills a little inviolate world, a little sanctuary where the Brotherhood of Man and the Fatherhood of God are not just words but living, breathing realities. . . .” (620)

That doesn’t sound very Mormon, certainly not like Erastus Snow or any other 19th-century Mormon leader, and some have cited it as further evidence that Whipple just didn’t understand Mormon spirituality. But there are two passages of scripture that could help us interpret the scene differently. Doctrine and Covenants 1:24 tells us that God speaks to his servants “in their weakness, after the manner of their language, that they might come to understanding.” Sure, it doesn’t sound like Erastus. It sounds like Clory. He’s speaking to her “after the manner of [her] language.”

He’s also speaking to her “in her weakness,” a phrase that restates Alma’s baptismal covenant at the Waters of Mormon to “bear one another’s burdens that they may be light” (Mosiah 18:8). In saying, “I’m not sure what a testimony is myself,” Erastus is taking upon himself Clory’s burden, her sense that she doesn’t have a testimony.

The deep irony is that, while Maurine Whipple portrays her faith community as bearing each other’s burdens, that community burdened her with the label of one who didn’t quite fit, indeed uses the very scene that celebrated their empathy as evidence she didn’t understand their spirituality.

If, instead, we choose to interpret the ending as evidence that she did understand Mormon spirituality, it becomes possible to ask why she chose to state that spirituality in terms most Mormons wouldn’t use. Veda Hale told me that she thinks Whipple wanted to relate Mormon spirituality to the great spiritual/mystical tradition, that she wanted to tell her non-Mormon readers that Mormon spirituality stands right alongside any of the great spiritual traditions.

She ought to be celebrated for that. . . .

Mormonism reasserted a high degree of physical detail, with Joseph Smith proclaiming God’s embodiment in the King Follett Discourse and “The Father has a body of flesh and bones as tangible as man’s; the Son also” (D&C 130:22). But Mormon descriptions of spirituality tend to be highly abstract. To use a platitude I’ve heard over and over in the last 25 or 30 years, “Trying to explain the Holy Spirit to someone who’s never felt it is like trying to explain the taste of salt to someone who’s never tasted it.”

That may sound like a solid, salt of the earth metaphor, but it’s really saying, “If you don’t know what a spiritual experience is I can’t tell you.” It’s a totally abstract statement—much more abstract than comparing one’s spirituality to the warmth and tenderness and affection and openness and joy and enigma and sensuality and generosity of —a Smile.

The Mormon answer to such abstraction is to invite the Holy Spirit to communicate one’s message to the readers or audience. This can create difficulties for an artist—who probably can’t assume readers will be aware of the Holy Spirit in the same way the artist is . . .

But most Mormon depictions of spirituality are not visual. Instead, they rely on the sense of touch. Two metaphors figure prominently when Mormons discuss spirituality. The first is the veil. In Mormon thought, the dead live on the same planet as the living. We don’t see them because a veil separates this world from the next, but we can sometimes feel their presence just as we can feel the presence of ther people in a room even if we can’t see them. This sensing the presence of the dead often happens in the temple, where people perform ordinances like baptism as proxies for the dead. “The veil is very thin in the temple” is a phrase commonly used to express the sense of the dead’s presence.

The second metaphor is the burning in the bosom. I’ll spare you all the jokes about heartburn. The important thing here is that “burning in the bosom” is used to describe a feeling of peace, joy, warmth, affection, reassurance—everything conveyed in . . . a smile.

I’m suggesting that Maurine Whipple’s images of the Great Smile and the Grand Idea are attempts to translate Mormon spirituality into terms non-Mormons might recognize . . .

Many LDS feel that Whipple did not re-present their spirituality faithfully. But I wonder how that might change if we changed our assumptions, decided that the image of the Great Smile is an attempt to relate our spirituality to a larger audience—a way of saying, “We are people just like you.”

.

I am so glad to read this. Thanks for finding and sharing!