Guest post by Robert Hodgson Van Wagoner, author of The Contortionists (Signature Press)

Guest post by Robert Hodgson Van Wagoner, author of The Contortionists (Signature Press)

Suspense is the locomotive pulling all good fiction, be it classic literature, contemporary literary fiction or the genre potboiler—if a narrative succeeds in drawing the reader along, it does so on the train of suspense. When I use the term suspense, however, I am not merely referring to devices related to plot. Rather, I am referring to tension and release in all its forms—the way consonants and vowels work with and against each other; the way words pile and bunch, then flow without restraint, only to pile and bunch once again; the way ideas juxtapose and compete for preeminence before shredding and reforming as something new; the way images appear and disperse, combine and refract to conjure colors and textures and shapes and motions wholly familiar or unexpected; the way setting and context give birth to antagonistic forces that propel the action forward; the way characters betray their own natures…the way they contradict their own beliefs…the way they raise the stakes by revealing and endearing themselves to the reader; and, yes, the way narrative withholds and reveals to create what John Gardner, in The Art of Fiction, calls “profluence”—a story’s forward momentum.

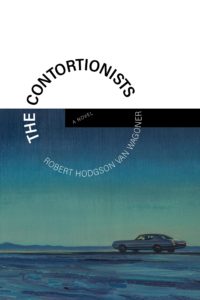

I love narrative suspense in all its forms. I’ve loved it, I suspect, since before I could read. I was raised by a mother, a voracious reader of fiction, who told me stories and read me books, by a father, a visual artist, whose images contained a narrative suspense all their own. (The oil painting featured on the cover above was made by my late father, Richard J Van Wagoner. Do you see what I mean about his paintings’ narrative suspense?) As an elementary school student, I could scarcely wait for the Scholastic books I would order to arrive. Even during the early grades, my favorite picture books contained some element of mystery—robbers or ghosts, an atmospheric, nighttime setting. But it was Mrs. Phyllis Shaw, Horace Mann Elementary School’s extraordinary librarian, who placed the first chapter-book mystery in my hands. Though I no longer remember the title and author (forgive me, it’s been nearly fifty years), I can still see the book, its blue and black cover, its dimensions smaller than most of the chapter books on the shelves around it. I remember precisely where it was located in the library, for I returned to it (and its sequels) many times. Thank you, Mrs. Shaw—I was utterly hooked. Hooked on suspense. So hooked, in fact, I spent the summer before my sixth-grade year selling frozen fish door-to-door so I could buy the entire library-bound collection of Alfred Hitchcock and the Three Investigators. Formulaic though they were, written by committee, I loved those books. I own them still. They formed the foundation of my most guilty reading pleasure.

But with time, alas, I began to see the machinery at work in most of the genre mysteries and thrillers I read. As is the case with all true junkies, the same dosage just didn’t deliver the same high. I simply couldn’t any longer find many genre suspense novels that carried the necessary punch. And so my tastes turned toward a more satisfying and lasting suspense I found in classic literature and contemporary literary fiction. The subversion and cooption, the sly twisting and turning and restructuring and abandoning, of the machinery delivered its own special kind of suspense. Literary fiction—which in my mind includes many literary crossovers—clutched me in ways few strictly genre novels any longer succeeded.

Once I’d written a literary novel of my own, it was inevitable, I suppose, I would eventually try to write a mystery/thriller that employed many of the elements one finds in literary fiction. By which I mean the following (by way of the questions I asked myself during the writing of said work): Could I coopt but subvert the machinery commonly found in the genre novels I’d loved growing up and thereby make something fresh and new? Could I create fully fleshed characters whose lives were real and whole and sympathetically realized? Could I employ a rich, textured language that was sonically pleasing yet transparent and subtle in its evocations? Could I address issues of relevance, discuss ideas that mattered, while still generating a page-turning “profluence?”

The Contortionists is my attempt at answering these questions and more. Whether I have succeeded or not is up to the reader to determine, but my goal was to write a literary crossover in which suspense was layered into the novel’s every element. As some may note, it took me a long time to produce a version that satisfied my intentions—some fifteen years of writing and revising, then revising and revising and revising some more. I am not easily satisfied by my own work, and I do not like to let go. But overall, I am content that this novel represents a worthy attempt at answering those questions and meeting those goals. And whether that attempt succeeds or not, I’ve come to love the characters who inhabit their story. I’ve enjoyed the untold hours we’ve spent fighting it out together.

A few semi-fun factoids: The manuscript’s first draft was 1000 pages. The published novel comes in at 358 pages (so many characters and scenes left on the cutting floor!). It went through dozens and dozens of hard revisions. I’ve read it many multiple times of that. Should I ever have occasion to read it again, I’ll find elements I’ll wish I’d written differently. If you have any interest, I’ll read The Contortionists to you—I narrate the forthcoming audiobook version.

Allow me to share the novel’s short, opening chapter:

In the Garden

1:12 p.m.

The neighbor, Natalie MacMillan, would tell essentially the same story as Melissa Christopher, the missing boy’s mother. They would both say the child had been gone twenty minutes before anyone noticed, twenty silent minutes book-ended by two telephone calls, the first from the mother to tell the neighbor five-year-old Joshua was on his way to the birthday party, the second from the neighbor to ask the mother if she had sent him yet.

Two hours later scarcely a person in Utah hadn’t heard the terrible news. But in the upper Ogden Valley near a town named Eden, Karley did not yet know her nephew had gone missing. Bare-bottomed, she bent to examine her peas and lettuces. They were up, tiny things yet, but up. It was a gift for Hans, this lingering. She could feel his eyes on her.

Smiling, Hans reached to the nightstand for his water. He enjoyed this view through the open French doors, his wife’s dark hair still riled from lovemaking. Playful Karley, she was childlike in gardens and skin. He returned the water to the nightstand and rolled from the bed, stretched, then gathered his jeans from the floor. Zipping and buttoning, he wandered through the open doors. At the edge of the deck, he wiggled his bare toes and contemplated the twenty-odd yards of wet grass between himself and his wife. The hard May rain had softened and the interloping mist braced his naked torso. He’d nearly decided to return for a shirt when Karley stood up.

Cocking an ear, she fingered back her hair. Yes, she’d heard correctly, the downshift whine of a vehicle slowing on the highway below. She listened to the car turn up their long drive, the cascade of wheels spinning fast in gravel. Smiling over her shoulder, she primly tugged down the hem of her T-shirt. It barely covered her bottom. She might almost make it to the house if she ran. Instead she turned back toward the highway, her gaze aimed at the gap in the shrub oak and ponderosa. When Caleb’s Jeep crested, moving much too fast, she and Hans exchanged a quick glance.

“You’re here?” the boy shouted. “We’ve been calling for over an hour!” Long-legged, he hurried through flowerbeds, over crowning boulders too massive to excavate.

Karley stretched the shirt to her bare thighs and watched her eighteen-year-old brother lumber into the garden, his approach heedless of all including the young plants he crushed beneath his feet. Karley received him with upstretched arms, hands reaching to still his face.

“Slow down,” she said. “I don’t understand what you’re saying.”

Hans started down the stairs. He could hear the boy’s voice but couldn’t make out the words. Karley said something, and again Hans failed to understand. Crossing the yard quickly, he tried to read lips. Karley stared up at Caleb’s face, gave her head an incredulous shake, then touched her throat and took a half step back. Turning–Caleb still talking, doing better now, making sense–she met Hans’s gaze.

She was a good athlete, Karley, sure-footed. She crossed the wet lawn at a sprint without slipping, her feet black to the ankles with mud.

Robert Hodgson Van Wagoner’s debut novel, Dancing Naked, received the Utah Book Award and the Utah Original Writing Competition’s Publication Prize. His short stories and interviews have appeared in periodicals, e-zines, and anthologies, and have been selected for various awards, including Carolina Quarterly’s Charles B. Wood Award for Distinguished Writing, Shenandoah’s Jeanne Charpiot Goodheart Award for Fiction, Sunstone’s Brookie and D. K. Brown Memorial Fiction Award, and Weber: The Contemporary West’s Dr. O. Marvin Lewis Award for Best Fiction. He resides in Washington state.