Guest post by Lynne Larson

In its July 2018 issue, the Ensign ran a story in its Latter-Day Voices section called “The Good People of St. George.” The brief piece was written by Claudio Gonzalez of Antofagasta, Chile, who recounted how as a boy he had seen a church movie showing President Lorenzo Snow praying for the people in southern Utah who were suffering from a severe drought. “Lord,” President Snow prayed, “bless the good people of St. George.”

Brother Gonzalez said the phrase, “the good people of St. George,” left a lasting impression on him as a youngster, and he always wanted to someday meet these faithful folks in faraway Utah, these people whose ancestors had earned a prophet’s prayer, these people of St. George whose goodness he could only imagine.

Later, as a man with college-age sons, Claudio Gonzalez saw an opportunity to visit St. George while he was in Utah to drop off one of his boys at Brigham Young University. Even though St. George was not on the itinerary and 260 miles from Provo, Brother Gonzalez insisted on making the trip. “I want to see the good people of St. George,” he said, remembering the phrase from the film he’d seen so many years before. The Gonzalez family made the journey, and Claudio Gonzalez finally got to fulfill his boyhood dream. He met “the good people of St. George” at last, and discovered they were good people, but really not much different from many other “good people” he had known throughout his life. His story in the Ensign ended with a beautiful lesson about where “good people” are always found, whether they live in Utah or Chile, or anywhere the faithful reside and congregate across the world.

Brother Gonzalez’s story touched me when I first read it, and I certainly appreciated and agreed with his ultimate conclusion at the time that “the good people of St. George” are indeed found wherever faithful Saints might gather. I still share that belief and love the idea of the St. George people in a boy’s imagination being symbolic of good people everywhere.

During the past two years, however, I’ve had reason to recall Claudio Gonzalez’s Ensign story often as my work has taken me on a journey similar to his. I have traveled to southern Utah, as well, conducting my own search for “the good people of St. George” just as Brother Gonzalez did. But while my journey certainly included the 260-mile modern freeway from Provo that Brother Gonzalez traveled, it also took me back in time, to the day in the 1930’s when a young woman named Maurine Whipple began taping handwritten pages to her bedroom wall, determined to organize her creative intuition into the story of her people. The masterpiece Whipple finally produced, under extremely arduous circumstances, became The Giant Joshua, considered by many to be the finest Mormon novel ever written. After re-reading it and the other Whipple literature I gathered, I was convinced again of what I firmly believed when I first read Joshua more than forty years ago. Maurine Whipple had given Mormonism an incomparable gift by simply introducing the rest of us to Erastus Snow, Lars Hansen, the Yeast Lady, Shadrach Gaunt, Brigham Young as we’d never known him, her unforgettable heroine, Clorinda MacIntyre, and the “whole heroic cavalcade,” of Dixie saints, “marching toward the deathless stars.” And though I still believe in Claudio Gonzalez’s conclusion about good people being everywhere, because of Maurine Whipple, I remain inspired by his first assumption: the good people of St. George were special all by themselves.

During the past two years, however, I’ve had reason to recall Claudio Gonzalez’s Ensign story often as my work has taken me on a journey similar to his. I have traveled to southern Utah, as well, conducting my own search for “the good people of St. George” just as Brother Gonzalez did. But while my journey certainly included the 260-mile modern freeway from Provo that Brother Gonzalez traveled, it also took me back in time, to the day in the 1930’s when a young woman named Maurine Whipple began taping handwritten pages to her bedroom wall, determined to organize her creative intuition into the story of her people. The masterpiece Whipple finally produced, under extremely arduous circumstances, became The Giant Joshua, considered by many to be the finest Mormon novel ever written. After re-reading it and the other Whipple literature I gathered, I was convinced again of what I firmly believed when I first read Joshua more than forty years ago. Maurine Whipple had given Mormonism an incomparable gift by simply introducing the rest of us to Erastus Snow, Lars Hansen, the Yeast Lady, Shadrach Gaunt, Brigham Young as we’d never known him, her unforgettable heroine, Clorinda MacIntyre, and the “whole heroic cavalcade,” of Dixie saints, “marching toward the deathless stars.” And though I still believe in Claudio Gonzalez’s conclusion about good people being everywhere, because of Maurine Whipple, I remain inspired by his first assumption: the good people of St. George were special all by themselves.

My journey through time was actually made with two colleagues, Andrew Hall, a history professor at Kyushu University in Japan, and Maurine Whipple’s award-winning biographer, Veda Hale. Together, we have compiled a collection of Whipple’s finest work—short stories, essays, magazine articles, and novellas—and published them with By Common Consent Press under one title, A Craving for Beauty: The Collected Writings of Maurine Whipple. The volume also includes several chapters of Cleave the Wood, Whipple’s planned sequel to The Giant Joshua, which focuses on the next generation, Clorinda’s children.

My journey through time was actually made with two colleagues, Andrew Hall, a history professor at Kyushu University in Japan, and Maurine Whipple’s award-winning biographer, Veda Hale. Together, we have compiled a collection of Whipple’s finest work—short stories, essays, magazine articles, and novellas—and published them with By Common Consent Press under one title, A Craving for Beauty: The Collected Writings of Maurine Whipple. The volume also includes several chapters of Cleave the Wood, Whipple’s planned sequel to The Giant Joshua, which focuses on the next generation, Clorinda’s children.

Hours of research in the Whipple Collection at Dixie State University were made more pleasant and possible with the invaluable assistance of staff members Kathleen Broeder (special collections chief librarian), Tammy Gentry and Tracey O’Kelly, marvelous ladies to work with and to know.

Having gained an affection for Whipple’s Joshua through the years, as well as a sincere fondness for St. George and her people, past and present, it was a privilege for me to participate in this venture. I have always considered it a tragedy that a great novel like The Giant Joshua remained generally unread and unappreciated by so many of my fellow Latter-day Saints, and this project seemed one way to possibly resurrect our greatest Mormon novelist and give her the honor she deserved. As a boy, Claudio Gonzalez became intrigued with the “good people of St. George” because of a church movie and Lorenzo Snow. I first became intrigued with the “good people of St. George” because of a book and Maurine Whipple. The words of each inspired both of us long after our first encounter. I have driven southward to St. George many times, but only in The Giant Joshua can I read the following lines and imagine Clory MacIntyre entering the valley, a naïve young girl of seventeen in 1861.

Having gained an affection for Whipple’s Joshua through the years, as well as a sincere fondness for St. George and her people, past and present, it was a privilege for me to participate in this venture. I have always considered it a tragedy that a great novel like The Giant Joshua remained generally unread and unappreciated by so many of my fellow Latter-day Saints, and this project seemed one way to possibly resurrect our greatest Mormon novelist and give her the honor she deserved. As a boy, Claudio Gonzalez became intrigued with the “good people of St. George” because of a church movie and Lorenzo Snow. I first became intrigued with the “good people of St. George” because of a book and Maurine Whipple. The words of each inspired both of us long after our first encounter. I have driven southward to St. George many times, but only in The Giant Joshua can I read the following lines and imagine Clory MacIntyre entering the valley, a naïve young girl of seventeen in 1861.

White and crimson, or black and yellow and blue — behind her and ahead and around her — spewed in fantastic violence, in every shade and nuance, the colors of this unreal landscape glittered with such intensity that she closed her eyes and for a moment her breath clung in her throat. She felt hemmed in with untamed, imponderable forces. This land was different from the gentle valleys of the North as she imagined hell would be different from heaven . . . . Shivering, she lifted her gaze beyond the valley to the west. There, continuing their mad dance, the ridges behind her joined hands with others and circling, tier on tier, concentric rings of color, vermillion, scarlet, maroon, or striped white and pink and gray . . . At the very vortex of this tangled network of canyons there was a long black hill standing smoothly and soberly in the midst of the frenzy about it. Uncle Abijah said that a similar black ridge faced it, although she could only see its crest from here, and that between the two black ridges lay the valley, the valley of sagebrush where she was going to spend all the rest of her life — the valley that was already named, President Young had told them, the city of St. George.

White and crimson, or black and yellow and blue — behind her and ahead and around her — spewed in fantastic violence, in every shade and nuance, the colors of this unreal landscape glittered with such intensity that she closed her eyes and for a moment her breath clung in her throat. She felt hemmed in with untamed, imponderable forces. This land was different from the gentle valleys of the North as she imagined hell would be different from heaven . . . . Shivering, she lifted her gaze beyond the valley to the west. There, continuing their mad dance, the ridges behind her joined hands with others and circling, tier on tier, concentric rings of color, vermillion, scarlet, maroon, or striped white and pink and gray . . . At the very vortex of this tangled network of canyons there was a long black hill standing smoothly and soberly in the midst of the frenzy about it. Uncle Abijah said that a similar black ridge faced it, although she could only see its crest from here, and that between the two black ridges lay the valley, the valley of sagebrush where she was going to spend all the rest of her life — the valley that was already named, President Young had told them, the city of St. George.

Always enthusiastic about my Mormon heritage and history, I had often been amazed by the power of good people who worked together for a worthy cause – the Stripling Warriors, the 1847 Pioneers — people who were valiant in their mission and in their spiritual resolve. But as a writer, I sometimes wondered, how could such devotion ever be sufficiently described? When I first read the following sentences from The Giant Joshua, I realized my question had been answered. The tabernacle in St. George was ever afterward a special place, and the temple, shining in a desert where even decent homes came at a heavy price, was no longer just a place where Brigham Young once stood and pounded his cane upon the pulpit.

The building arose from the barren ground like a great white wedding cake. It was eighty-four feet high to the top of the parapet, battlemented like an old castle, and there was a hundred-and-thirty-five-foot tower on top of that. There were twelve gothic buttresses along each side and five along each end, and the three-tiered spire had panels to balance the line of buttresses. Inside, there were two spiral staircases winding upward the entire height of the building, eleven rooms in the basement and one main room above, with eight smaller rooms around it.

The building arose from the barren ground like a great white wedding cake. It was eighty-four feet high to the top of the parapet, battlemented like an old castle, and there was a hundred-and-thirty-five-foot tower on top of that. There were twelve gothic buttresses along each side and five along each end, and the three-tiered spire had panels to balance the line of buttresses. Inside, there were two spiral staircases winding upward the entire height of the building, eleven rooms in the basement and one main room above, with eight smaller rooms around it.

Long before the ceremonies were to start, a vast throng of people wandered around the block, squinted upward from the roadway, felt of the solid rock walls with their hands as if to bolster the evidence of their eyes. A Temple that would cost a million dollars. The world would have said it couldn’t be done, and so they did it.

‘Do you remember the angels in the sky when we dedicated the Nauvoo Temple?’

Keturah Snow sat in her husband’s coach and studied the chaste white walls through half closed eyes.

‘And the rushing sound,’ said Martha in an awed voice, ‘the “spirit of God like a mighty rushing wind.”’

‘I remember the tiled floors and the Bible scenes painted on the plastered walls, and the font they said was a copy of the baptistry in King Solomon’s Temple,’ said Hannah Merinda, ‘but it wasn’t as grand as this.’

‘No,’ sighed Aunt Ket. ‘Nothing could be as grand as this!’

To these lines we can now add examples from essays like “The Miracle of the Spillway,” Whipple’s dramatic tale of the day Brigham Jarvis and the men of Dixie finally conquered the Virgin River in 1885. “That night Brig Jarvis couldn’t sleep,” she begins, and from there the stunning victory is related in colorful detail.

Brig Jarvis sat up in bed . . . there was the river with a hogsback of rock cutting it almost in half, forcing the surging waters of a flood to slow down, to spill harmlessly over the reef, or breakwater.

The next day, staring at the desolate waste of mud where the pile dam had been, Brig still saw the hogsback. All at once he understood what it meant and marveled that he had not perceived the connotation long before. ‘How simple!’ he cried aloud. ‘What fools we’ve been!’

Charley Seegmiller, working beside him, looked up from his shovel and scowled, ‘Be ye daft?’

But Brig was too agitated to care. ‘Don’t you see?’ he shouted. ‘No dam, no matter how large, can contain a rising wall of water unless it has an outlet. Water’s like steam. It has to escape!’

The story goes on. There is struggle and hard work and mistakes, and the accidental drowning of a team of horses, but as Whipple concludes . . .

The details don’t matter . . . the point is that the idea was right — and so the spillway dam has held from that day to this. Coincidence? Consider the odds: Brig Jarvis was an unlettered man in an unheard of corner of a poverty-stricken territory — at the time, Utah wasn’t even a state. Neither he nor Erastus Snow, who had the original dream, had ever heard of the ancient Egyptians or Romans who first utilized the spillway concept. Yet by some magic, that concept came to Brig Jarvis out of the ether over three thousand years of time . . . take time to marvel at the green, green fields [as you drive today around Dixie], the hundreds of acres of sugar beet seed watered all winter long by the once terrible Virgin River . . . That, my friend, is the miracle of the spillway.

The details don’t matter . . . the point is that the idea was right — and so the spillway dam has held from that day to this. Coincidence? Consider the odds: Brig Jarvis was an unlettered man in an unheard of corner of a poverty-stricken territory — at the time, Utah wasn’t even a state. Neither he nor Erastus Snow, who had the original dream, had ever heard of the ancient Egyptians or Romans who first utilized the spillway concept. Yet by some magic, that concept came to Brig Jarvis out of the ether over three thousand years of time . . . take time to marvel at the green, green fields [as you drive today around Dixie], the hundreds of acres of sugar beet seed watered all winter long by the once terrible Virgin River . . . That, my friend, is the miracle of the spillway.

In her 1952 article, “Arizona Strip: America’s Tibet,” Whipple reminded the reader that there is a “myth-breeding wilderness” just south of St. George where “dark legends were muttered in in the little towns along its perimeter.” The Strip was inhabited by characters with names like Slats Jacobs and Skunk-Eye, a fellow “with a Falstaffian belly with friends in half a dozen states who would vie for the privilege of buying his overcoats and grub.” No, Whipple did not limit her writing to the history of Mormon colonization. Real people appealed to her, no matter their stripe, and she made them vivid, colorful, and natural, wherever she found them, courageously infusing honesty rather than unblemished heroism in her writing.

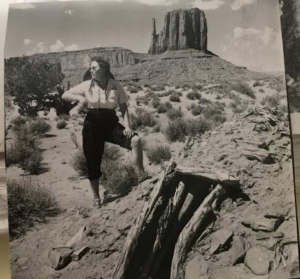

Whipple successfully published stories and essays in Collier’s and The Saturday Evening Post and worked hard to produce travel articles to promote her beloved Dixie. Health problems and a series of failed romances proved debilitating as she unsuccessfully struggled to write the Joshua sequel and live up to the promise of her gift. But all of Whipple’s work, published and unpublished, reflects her remarkable literary genius, even the “small” pieces that have little to do with Dixie. Her short story, “Mormon Saga,” which will be published for the first time in an upcoming issue of Dialogue, is an excellent example.

Because it dealt harshly and realistically with polygamy, “the good people of St. George” gave The Giant Joshua mixed reviews when it was first published by Houghton-Mifflin in 1940. But the book has outlived the mild censorship of the past. “Time has proven that the novel is bigger than even valid criticisms,” says Hale, who admits that Whipple let any negative response stifle her subsequent success far more than it should have. While Whipple’s own family members dismissed the book and were generally embarrassed by it, many hometown friends congratulated her, recognizing her accomplishment. The words of her high school principal, Joseph K. Nicholas, sum up the messages of several. “You have written beautifully [about] the achievements of a superior people through their purposes and emotions. The background of your great study is true, therefore, your book will live.”

If Whipple’s neighbors were curious but cautious readers, The Giant Joshua proved to be a literary sensation in the East where one editor said the book made him think Mormons were “a wonderful people,” and another called Joshua’s heroine, Clory MacIntyre “one of the most appealing women in modern fiction.” Critic Avis M. Devoto added, “Perhaps Miss Whipple’s greatest achievement is getting on paper the social history which brings the period into focus. Here are the engrossing details of living—the clothes, the food, the remedies, the deaths and births, the preparing of bodies for burial. These people appear in the round—a rough, hardy lot, rough of tongue, bursting with vitality.” Devoto’s husband, Bernard DeVoto, offered what was perhaps the finest praise of all. “The Giant Joshua,” he wrote, “is excellent reading and it catches a previously neglected side of the Mormon story and that is the tenderness and sympathy which existed among a people dogged by persecution and hardships, forced to battle an inclement nature for every morsel of food they ate and to struggle for every moment of genuine happiness.”

It is that struggle which Maurine Whipple immortalizes in The Giant Joshua and in her other literature, the struggle Clory thinks of at the end of her own story.

She would not have changed a moment of it. Tomahawk and war whoop, bran mush and lucerne greens, Virgin bloat, the Year of the Plagues, the Reign of Terror. She felt a detached pity for the generations yet to come who couldn’t plan and build a world . . .

Yes, I agree with Claudio Gonzalez. The “good people of St. George” are everywhere. But some of them still thrive in Maurine Whipple’s Red Rock country as they always have. Tammy and Tracy, those wonderful staff members in the library at Dixie University are still there, keeping Maurine Whipple’s literary heritage protected for future generations. And their long- departed ancestors remain as well. Their voices echo on the canyon wind and linger in the rapidly changing world between Hurricane and Washington, Santa Clara and St. George. They would hardly recognize the place, good Erastus Snow, Lars Hansen, the Yeast Lady, old Shadrack Gaunt, David Wight, Willie and Sheba, Maurine’s beloved maternal grandmother, Cornelia McAllister, after whom Clory was modeled. And, of course, Clory herself, “the most appealing woman in modern fiction.” Some of these folks linger only in spirit, some in the flesh through their descendants. They live in Dixie still, on Whipple’s eloquently crafted pages. Because of her, it’s still possible to know and love them, and forever claim them as our own.

Lynne Larson is one of the editors of A Craving for Beauty: The Lost Works of Maurine Whipple (BCC Press). She turned her full attention to reading, writing, and promoting western literature and history after an award-winning career as an educator in Idaho. She has published several novels, short stories, articles, essays, and magazine columns of her own, but considers her contribution to A Craving for Beauty perhaps her most important work. She is a graduate of Brigham Young University and has an M.A. degree in English from Idaho State University in Pocatello. She and her husband, Kent, are the parents of three children.

I enjoyed this article! I read The Giant Joshua over 50 years ago and I have ancestors who settled St. George. I am eager to read more of Maurine’s writings.

Thank you, Lynne.

This is wonderful writing, Lynne! Your essay certainly rises to the standards Maurine set with her colorful language and stye. And I love the photograph of he purple and pink mountains all of us who have lived in St. George have grown to love! I am reading”Dixie Saints” by Douglas Alder, and in it I can see how many of the “good people of St. George” are available for all of us to care for, meet, and celebrate by adding our own artistic observations. You have stimulated us with this excellent report, and all of us will be happy to read of Maurine’s “cravings for beauty.” I am so grateful you introduced this work in such an outstanding way. To echo Suzanne Stott’s gratitude, “Thank you, Lynne!”