We are devastated to hear of the passing of Béla Petsco, the author of one of the most remarkable works of modernist Mormon literature, the short fiction collection Nothing Very Important and Other Stories.

We are devastated to hear of the passing of Béla Petsco, the author of one of the most remarkable works of modernist Mormon literature, the short fiction collection Nothing Very Important and Other Stories.

Béla András Petsco (also known as William Andrew Petsco) was born March 10, 1943, the third child of Béla (William) and Etelka (Ethel) Bódi Petsco, in Queens, New York City, and lived among his extended Hungarian-American family. He first became interested in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints  after seeing the movie Brigham Young. He looked up the Church in the library, and was drawn to the principles of eternal marriage and baptism for the dead. He contacted missionaries, and was baptized around 1965. He remained firm in his faith throughout his life. Not long after this he was married, and the couple lived in California. Tragically, his wife died in childbirth. After his wife’s passing, he decided to serve a mission, and was called to the California South Mission, where he served from 1967 to 1969.

after seeing the movie Brigham Young. He looked up the Church in the library, and was drawn to the principles of eternal marriage and baptism for the dead. He contacted missionaries, and was baptized around 1965. He remained firm in his faith throughout his life. Not long after this he was married, and the couple lived in California. Tragically, his wife died in childbirth. After his wife’s passing, he decided to serve a mission, and was called to the California South Mission, where he served from 1967 to 1969.

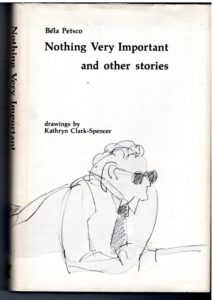

In 1970, Petsco started studying as an undergraduate at BYU, and went on to receive a Master’s degree in English, where his advisor was Richard H. Cracroft. His 1977 Master’s thesis, Nothing Very Important and Other Stories, was a series of connected short stories about LDS missionaries serving in Southern California and Arizona, based on Petsco’s own experiences. An expanded version was published in 1979 by a small Provo publisher (Meservydale Publishing) and was reissued in a trade paperback under Signature’s Orion Books imprint in 1984. The collection won the 1979 AML Short Fiction Award, and was hailed as a milestone, the first view of missionary life from someone born and raised outside the Wasatch front. It was to be the second in a trilogy about Mihaly Agyar, a character based on his own life. The first novel was called Salem, about his marriage and the death of his wife, a chapter of which appeared with that title in BYU’s literary magazine the Wye in 1974. Petsco destroyed and rewrote the manuscript for Salem more than once.

In 1970, Petsco started studying as an undergraduate at BYU, and went on to receive a Master’s degree in English, where his advisor was Richard H. Cracroft. His 1977 Master’s thesis, Nothing Very Important and Other Stories, was a series of connected short stories about LDS missionaries serving in Southern California and Arizona, based on Petsco’s own experiences. An expanded version was published in 1979 by a small Provo publisher (Meservydale Publishing) and was reissued in a trade paperback under Signature’s Orion Books imprint in 1984. The collection won the 1979 AML Short Fiction Award, and was hailed as a milestone, the first view of missionary life from someone born and raised outside the Wasatch front. It was to be the second in a trilogy about Mihaly Agyar, a character based on his own life. The first novel was called Salem, about his marriage and the death of his wife, a chapter of which appeared with that title in BYU’s literary magazine the Wye in 1974. Petsco destroyed and rewrote the manuscript for Salem more than once.

After receiving his Master’s degree, Petsco taught composition for a time as an adjunct in the BYU English Department. However, some of the more controversial passages in Nothing Very Important, including depictions of mission politics, seduction, dishonesty, homosexuality, and insensitivity, appear to have made publication of the book and employment at BYU difficult. Gary Bergera and Ronald Priddis, in their book Brigham Young University: A House of Faith, claim that the book was rejected by the BYU Press because its treatment of missionary life was “too controversial”. They also record a 1979 letter from BYU President Dallin H. Oaks to Apostle Ezra Taft Bension, which stated, “The book [i.e., Nothing Very Important], of which I had no previous knowledge, surely does not strengthen [the author’s] efforts for employment at BYU.” (Oaks to Benson, 16 Oct. 1979.)

In 1982, a group of students and former students, led by Dennis Clark and Harlow Clark, put on a readers-theater version of Nothing Very Important at Orem Public Library. The play included a scene in which a missionary was seduced by a woman, which resulted in some criticism from the community, and Petsco deciding not to allow any more performances of the play. He appears to have been employed at BYU until around 1982, when his contract was not extended.

Around this time Petsco began suffering from serious health problems. His decline in health, together with his disappointment with those who had rejected his writing, dissuaded him from completing or publishing any more major literary works, one of the great tragedies of Mormon literature. Dennis Clark and Harlow Clark convinced him to publish some poems in Sunstone and Irreantum, and he completed an opera libretto about Joseph Smith’s last days, titled “And on to Carthage”, which was never published.

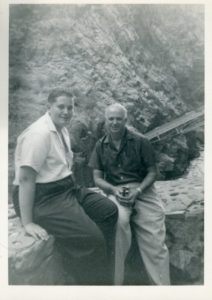

His widowed father came to live with him in Provo for a time, until he passed away in 1999. At some point Petsco lost the ability to walk and had to live in assisted living facilities in the Provo area. Since 2010 Sam Brooks has been his primary caretaker. Béla passed away on May 12, 2022.

His widowed father came to live with him in Provo for a time, until he passed away in 1999. At some point Petsco lost the ability to walk and had to live in assisted living facilities in the Provo area. Since 2010 Sam Brooks has been his primary caretaker. Béla passed away on May 12, 2022.

Funeral services will be held at 2:00 p.m., Wednesday, May 18, 2022 at the Berg Drawing Room Chapel, 185 East Center Street, Provo, Utah. Friends may call from 12:30-1:50 p.m. prior to services. Interment, Provo City Cemetery. Condolences may be expressed to the family at www.bergmortuary.com.

Béla Petsco’s published works

“Salem”. Wye, 1974. (short story, an excerpt from a planned novel)

“The Mustard Seed”. In Twenty-two Young Mormon Writers, ed. Richard Cracroft and Neal Lambert. Provo: Communications Workshop, 1975. (short story)

Nothing Very Important and Other Stories. Meserveydale, 1979. Orion/Signature, 1984. (short fiction collection/novel)

“Carved in the Soft-stone of a Tomb”. Sunstone 11:1, January 1987. (poem)

“And She Loved to Dance” and “Elegy”. Irreantum 4:3, Autumn 2002. (poems)

Reviews of Nothing Very Important and Other Stories

Richard H. Cracroft. “Seeking ‘the Good, the Pure, the Elevating’: A Short History of Mormon Fiction, Part 2. Ensign, July 1981.

Béla Petsco’s Nothing Very Important and Other Stories (1979) traces, in independent but tenuously related short stories, and in a manner similar to Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio, the unusual missionary experiences of Elder Mihaly Agyar, an LDS missionary in Southern California. Petsco’s book underscores the continuing interest among LDS writers in attempting to capture, in fiction, the essence of a mission.

Elouise Bell. “Stories About People Who Happen to Be Mormons”. AML Newsletter, 3:4, September 1979

Despite its title, Bela Petsco’s new book, Nothing Very important and other stories, is important and worth serious consideration. Petsco, who published the book himself, is publicizing it with the tag, “Stories about people who happen to be Mormons,” but that’s not quite right. The people don’t happen to be Mormons, they are Mormons because Mormons and Mormon problems are a central part of Petsco’s knowledge and experience, and it’s the ambivalence of the Mormon lifestyle that he has chosen to deal with. Were his characters Catholic or Jewish or agnostic, they would be entirely different people with entirely different conflicts. But perhaps what Petsco wishes to emphasize in using the tagline is that his characters are human beings, flesh and blood creature who are men and women first and Latter-day Saints next. Indeed, it is when the realism of the human animal encounters the idealism of the Mormon soul that the author’s best stories result—as in “The Shell,” the story of a sensitive, idiosyncratic loner who tries with painful awareness to become a satisfactory missionary but simply cannot find enough support in his world to sustain life. The story, though dealing with individual sensitivity and the problems inherent in its excess at either end of the spectrum, is not over-wrought or precious, but bittersweet told through a narrative choice that is both ironic and compassionate.

Indeed, it is that particular voice that makes Nothing Very Important significant.

Here is a collection of fiction pieces—not quite stories, many of them, some critics are calling the book a “fragmented novel.” Whatever.—that does what so many LDS readers have looked for literature to do: it deals maturely and unflinchingly with the ambiguities involved in being a Latter-day Saint in the twentieth century; it offers no easy answers, indeed few answers at all; yet, it is completely free of bitterness and the hard, grating rasp so often found in books that purport to “tell it like it really is.”

The book’s central characters is Milahly Agyar, a convert of Hungarian ancestry (like Petsco himself), working as a missionary in California and Arizona. Agyar’s age (he is perhaps five or six more years older than the average missionary), his convert status, his exotic genealogy, and his artist’s temperament make him a rich, perceptive intelligence through which to tell the various tales.

Though Petsco’s writing is not without flaws, it is smooth, professional, and highly readable. He has yet to master the integration of theme and narrative in such a way as to produce a self-contained short story that really feels like a short story, yet these pieces taken together do give us the satisfaction that a short novel gives.

Petsco is a major new talent on the Mormon letters scene, and his first book can be read and recommended without any serious reservations, but with whole-hearted pleasure.

Elizabeth Shaw, Sunstone, March-April 1980.

I haven’t been on a mission. And I don’t feel bad (momentary foot shuffling, only) when I say that I never wanted to go on a mission. But Bela Petsco’s Nothing Very Important and other stories makes it clear that a mission presents peculiar opportunities, not only for spreading the word but also for thinking about it. The questions Petsco’s characters think about aren’t all that new. Bob Elliot’s Fires of the Mind and Christy Ackerson’s Tales from a Tracting Book, for example, explore more thoroughly dilemmas of faith and fact, obedience and integrity, love and labels. And other LDS fiction writers have also confronted the particular problems of mission politics, seduction, dishonesty, homosexuality, and insensitivity.

What, then, is my delight in Nothing Very Important? It has little to do with plot and a lot to do with feeling. A reader’s feelings about himself, his friends, and his beliefs when he’s through with a book are not an irrelevant standard despite their subjectivity. And by that standard, this is an unusual book.

The mood that emerges from Petsco’s understated, almost off-hand prose allows me to face–without guilt–the cultural vagaries I assume by virtue of my membership in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. And that’s a major accomplishment. There is no Mormon past haunting Petsco’s characters–no lingering odor of blood atonement or decaying hometowns or unacknowledged indiscretions.

Through Elder Mihaly Agyar, Hungarian convert from Brooklyn, we have in each day a refreshing present reality. He shows it’s possible to be committed but also free of the Mormon self-consciousness, collective or personal.

Sufficient to the day are the problems Agyar encounters, of course. A fellow missionary–a friend–who commits suicide. A single woman he admires with her own particular tragedy, “overly ordered,” like her front yard. The young Utah mother of five who escapes to California. Her husband, who sends flyers (complete with photograph) through the wards there to locate her. But eighty-two-year-old Lena Gill knits her way into Agyar’s missionary life, too, as, while visiting with him, she recollects her past without rancor. And there is the Mormon woman who stands by her man. And the little, fortunate coincidences. “A mission is a mixture,” says Agyar in his homecoming report, “something to be experienced ….”

I guess what I’m saying is that this is a book about converts–about perpetual rebirths. Even the missionary is a convert. And liberally laced throughout the book are characters who keep us hoping.

What Petsco makes of the mission is kind of a second second-estate, with ambiguity and sensitivity the lessons to be learned–or, in gospel terms, faith and love. But there is no Sunday School epigram. From the title to the last line of the last story, the book modestly eludes simplification.

Despite its title, despite its understated style and tone, despite its impressionistic vignette structure, Nothing Very Important and other stories accumulates an intensity that is almost cathartic by the book’s end. Like a Bartok folk song, it is quick and clear and complex and renewing. In the words of Elder Agyar’s mother, “I feel ever so better today because of it.”

Wm Morris. AML Review, 2002.

I first came to know Bela Petsco through his silence. I don’t remember where. Some essay on Mormon literature, I believe, that mentioned that he hadn’t published any fiction since his groundbreaking collection of short stories. And shortly afterward his name was invoked on the AML-List where I was lurking at the time. His name was invoked in respect tinged with sadness and frustration. I don’t remember the thread topic or who (there were several) brought his name up, but I, hungry Mormon lit. novice that I was, imprinted it in my mind. And though his name came up again in my studies and discussions on the AML-List, what Petsco meant to Mormon literature remained hazy for me. The impression I carried was of a promising young writer gone silent, perhaps intimidated by the burden of expectation, possibly bowed by an unsympathetic Mormon audience. I’m sure it’s a false impression. And it feels strange to speak of him like this — especially to those who know him and his work from when it was freshly ripened. But I can’t cover the distance and treat his work as if it has just been published, so that has colored my reading and this review.

Nothing Very Important and other stories is a collection of 20 connected short stories punctuated by brief (a paragraph or two) bits of narration or description or dialogue. Most of the stories are narrated from the point of view of Elder Mihaly Agyar, an older convert born of Hungarian immigrants. But not all. The first story takes place shortly before his mission to Southern California and Arizona; the last two stories take place shortly after his return to his home in New York City.

Agyar is not a model missionary — he breaks mission rules. But only the ones he perceives as trifling. As an older missionary and recent convert, he finds the bureaucratic trappings of mission life amusing and frustrating. He remains conflicted about the emphasis on the number of baptisms and steadfastly credits other elders for “his” converts (the story “Numbers” deals directly with this conflict and also exposes readers most explicitly to Agyar’s thought processes — it’s a masterful work of Mormon discourse interiorized and in conflict). But throughout the stories he maintains a strong belief in the importance of the gospel and especially in connecting with and loving others.

What happens in these stories is sometimes relatively insignificant; sometimes it’s shockingly real. People, even missionaries, make mistakes and sin. The style is fairly sparse. Some of the stories are quite short. But things are said or done because of Agyar’s presence, because people — elders, members, investigators — open up to him. The flow of energy, of attraction and frustration and hope, is almost always towards him. He is a touchstone both for the reader and the people around him.

I’m not sure how to label it, but the flow of the stories feels to me like memories of a mission — a mission recalled. The connections between stories aren’t always clear. Certain moments, certain attractions remain, but they can’t all be tied together in a package and adorned with a prim bow. The short paragraphs between stories add to that effect. They often capture an archetypal moment or theme of mission life, a gesture or conversation or attitude. But the stories themselves create that feeling too, and, in the end, it’s obvious that the form of the collection is recreating Agyar’s own attitude towards his mission. All the events and places and people add up to “no form — no pattern” (207).

From Agyar’s homecoming talk: “A mission is neither all good — nor is it all bad. A mission is a mixture. It is something to be experienced” (191).

I am glad that I finally read Nothing Very Important and other stories. My mission experience was somewhat different, but my memories of it remain fragmented. Reading these stories was a resonant experience.

Perhaps it’s my peculiar critical view or the twenty intervening years of Mormon cultural history, but this collection seems naive. No. Simple is probably the better word. Maybe even innocent. What I mean is that the stories demand to be read as just that — stories. Trying to tie them into large ideological discussions and concerns is a futile, arrogant gesture. So I guess I’m defending Petsco’s silence even thought I know nothing about it. These stories deserve readers who will react to them on a personal level — readers who will cringe and cry, exult and mourn. Readers who will interact intensely with the text, yet at the end, not draw any conclusions or insist on interpretation, but will, with Agyar, shrug their shoulders and say that, well, it was nothing very important. I’m sure these readers existed in 1979. They do now. But there should be more. And they should be Mormon.

In short, this collection should be republished. With the surge of fictional mission narratives that have been published in the past five years, it’s time for this one to reappear. I don’t know if it would find a wide audience, but at least it could find the next generation of those Mormon readers who have similar reading sympathies as those who championed it when it first came out. I had to wait two months for my university library to order it from BYU. And I’d gladly pay for a used copy (including shipping) if anyone has an extra one.

Love that collection.

Appreciated this additional insight into Bela’s life.

On second Saturdays I serve lunch at the Food and Care Coalition in Provo, which would be just a short walk from the care center Bela was in, if not for the railroad tracks. A couple of months ago I stopped by and knocked on his door, and it was locked. The aid told me he had gone home, but they were keeping the room till the end of the month in case he had to come back. I called him. He told me that because Sam had been living there and wired it for computers so he could work from home, and is a capable caretaker, Bela’s hospice decided he could go home. However, Sam was not there at the moment to let me in, so I stopped by the next month. He gave me a couple of dozen CDs, and we spent an enjoyable hour together.

I was going to call him this afternoon, but when I got on the bus to go to the Food and Care Coalition, I checked my email and found a letter from Andrew Hall, with the subject line, “Bela Petsco’s Passing.” I had a copy of Nothing Very Important with me (one of three) so I read three of the stories on the way home. The book is a novel told in a series of interconnected stories where Mihaly Agyar is either a main character, or someone the others talk about. In between the stories is a series of vignettes, like the intercalary chapters in The Grapes of Wrath. Here’s one that got him in trouble:

Agyar walked into the living room. Snowfield was on the floor doing push-ups. Agyar watched him a while, then snapped his fingers and said, “I know! Missionary intercourse.”

He told me he wasn’t thinking of sexual imagery there, that back East “intercourse” didn’t have a primarily sexual meaning, that he was thinking of social intercourse, and thought it was a perfect way of suggesting that two elders weren’t getting along–that Snowfield was doing pushups to avoid talking to Agyar, I suppose.

He said if he had known the connotation it would have for readers in Utah he wouldn’t have included it in his MA thesis, but it was there, and he wasn’t going to remove it. He had asked Janice Cracroft what he could have done to highlight the social aspect of “intercourse,” and she said he couldn’t have.

Anyway, the vignette comes between “Two Minutes before Midnight,” one of the stories about Agyar’s friendships with troubled missionaries, and “Point Loma,” which shows a post-mission resolution to the missionary’s troubles. Then the next story (after a vignette about going to Ensenada because the mission president had forbid the missionaries to go across the border to go to Tijuana, “Now remember, we did not cross the border to go to T-j–our destination was Ensanada.”) is Snowfield telling another elder about him and Agyar “Riding Around One Night” with a member who was a police officer. The tone of Snowfield’s story is affectionate towards Agyar, suggesting they solved the problems between them.

It’s a remarkable book, and he was full of interesting stories about his family, and New York in the 40s and 50s and cross country travel before Eisenhower decided the country needed an interstate freeway system. I kept thinking, “You should be recording these stories,” and I should have asked him if he minded my recording him. I told him I’d like to do a recording on the StoryCorps app and send it to the Library of Congress.

I will miss him greatly, and I greatly appreciate his counsel that I need to write more, and editing other people’s writing, like I do at wok, didn’t count. I had to do my own writing.

I’m sorry to hear of Bela’s passing. I worked with him too at BYU in the 80s and 90s. Thank you for this kind report.

RIP Bela Petsco. His volume of Mormon shorts “Nothing Very Important and Other Stories,” was a seminal work of Mo-lit for me at BYU. I still have the copy after all these years.

Here is the video of Bela’s funeral service. The bishop read Bela’s lovely poem “Elegy”, which was published in Irreantum.

https://www.bergmortuary.com/obituaries/Bela-Petsco/