A guest post by the poet J. S. Absher.

A guest post by the poet J. S. Absher.

I grew up in the mountains of southwest Virginia and northeast North Carolina, a land rich in family stories and family storytellers. A couple of my family’s stories go back to the end of the Civil War. In one, a soldier walked from his Yankee POW camp in New York to the house on Dog Creek (a house still in the family) in the mountains of North Carolina. He must have been filthy and starving; according to family legend, on his return he was welcomed with a feast, he ate more than his body could tolerate and he died in agony. Some stories had living witnesses. My mother’s father was murdered in 1938, 13 years before my birth. And some are part of my own story, as when my father killed himself 45 years ago, when I was in grad school at Duke. His father was illegitimate but he was recognized as his father’s son and welcomed at family events. My grandfather fathered at least one child by another man’s wife. Although he was bad-tempered and verbally abusive to his wife and children and even (though far less often) his grandchildren, this child has only fond (if sparse) recollections of him.

I did not know all these things as a child but knew enough to understand that those who gave us life were flawed, often hard to live with, sometimes guilty of grievous sins, imperfect in giving and accepting love. This has been an important theme of my poetry.

When I was five or six, my mother was visited in dream by Jesus just before the missionaries knocked on her door and found her receptive to Joseph Smith’s vision. She’s nearing 90 and has served three times as Relief Society president, the last time in her 80th year. When I was a child, she fervently believed she would be alive to greet Christ at His second coming, but perhaps that belief is waning as she prepares to meet Him as we all will. When I was a teenager, I had a waking vision of the intelligences hiding in or behind the leaves of a black cherry on the edge of the yard crying “holy, holy, holy.”

When I was at BYU, a friend who was very enthusiastic about my poetry suggested I write a Mormon epic. But from Paradise Lost, I understood a little of the daunting effort required, and I thought that I would more likely be a Southern writer. I almost escaped being a writer at all. My first book, The Burial of Anyce Shepherd (Main Street Rag Publications, 2006) was not published till more than 30 years later. It recounts my maternal grandfather’s murder and my grandmother’s fifty-year widowhood. The killer’s reasons are not clear—family stories relate differing motives, most reflecting ill on my grandfather—but the one constant is racial: my grandfather was a white deputy sheriff, his killer an African American well-known to my family and possibly a partner with my grandfather in bootlegging liquor. In answer to my enthusiastic friend, I could have quoted Czeslaw Milosz, had I then read him: “The awareness of one’s origins is like an anchor line plunged into the deep, keeping one within a certain range. Without it, historical intuition is virtually impossible. That is why a writer of our century, William Faulkner, [confined] his stories … to the borders of a single county” (Native Realm (Doubleday, 1968), 20). I began as a Southern writer, working within the frontiers of a family, but over time my range has expanded, perhaps without losing touch with my origins.

When I was at BYU, a friend who was very enthusiastic about my poetry suggested I write a Mormon epic. But from Paradise Lost, I understood a little of the daunting effort required, and I thought that I would more likely be a Southern writer. I almost escaped being a writer at all. My first book, The Burial of Anyce Shepherd (Main Street Rag Publications, 2006) was not published till more than 30 years later. It recounts my maternal grandfather’s murder and my grandmother’s fifty-year widowhood. The killer’s reasons are not clear—family stories relate differing motives, most reflecting ill on my grandfather—but the one constant is racial: my grandfather was a white deputy sheriff, his killer an African American well-known to my family and possibly a partner with my grandfather in bootlegging liquor. In answer to my enthusiastic friend, I could have quoted Czeslaw Milosz, had I then read him: “The awareness of one’s origins is like an anchor line plunged into the deep, keeping one within a certain range. Without it, historical intuition is virtually impossible. That is why a writer of our century, William Faulkner, [confined] his stories … to the borders of a single county” (Native Realm (Doubleday, 1968), 20). I began as a Southern writer, working within the frontiers of a family, but over time my range has expanded, perhaps without losing touch with my origins.

That first book was published when I had been inactive in the church for seventeen years. It ends with my grandmother’s vision of her mourners dreaming of resurrection and with a revelation of God’s love—He is a fisherman “angling for them all, / hooking and crooking those well-worn lines,” lines by a wary almost-believer.

That first book was published when I had been inactive in the church for seventeen years. It ends with my grandmother’s vision of her mourners dreaming of resurrection and with a revelation of God’s love—He is a fisherman “angling for them all, / hooking and crooking those well-worn lines,” lines by a wary almost-believer.

My next book, Night Weather (Cynosura, 2010), consists largely of haiku-like short poems (“the white-faced cattle / muzzle down in the grass / March rain”), organized by season, with longer poems  placed midway in each season and between seasons. After years of writing poems to come to terms with my father’s suicide, these poems were a relief. Mouth Work (St. Andrews University Press, 2016) includes poems about my father’s life and my childhood. By the time the book was published, my wife had been baptized, I had returned to fellowship, and we had encountered a delightful family of refugees from a camp in Rwanda. The youngest son joined the church shortly after my wife. The poem reflecting this renewal of life is “A Song”:

placed midway in each season and between seasons. After years of writing poems to come to terms with my father’s suicide, these poems were a relief. Mouth Work (St. Andrews University Press, 2016) includes poems about my father’s life and my childhood. By the time the book was published, my wife had been baptized, I had returned to fellowship, and we had encountered a delightful family of refugees from a camp in Rwanda. The youngest son joined the church shortly after my wife. The poem reflecting this renewal of life is “A Song”:

bless the safe place we have made,

the wooden bowl on the table,

the fruit that fills it, the gnats

eating the ripe fruit, the fruit

of prayer and meditation;

and bless the headboard in whose

shadow we dream the tree

whose fruit we are—logger,

surveyor, poet and spouse,

lads: same tree, same fruit.

Mouth Work concludes with a poem where each cherry on a tree cries out “Holy! Holy! Holy! To the Lord—/the Lord of Listening and of Metaphor/who leads us to graze by the moving water.”

My latest book, Skating Rough Ground (Kelsay Press, May 2022) reprises many of these themes—the life and death of my father and his mother and my childhood as an observer and reader (in Flying Above the Steeple). One section (What Sorrel Is For) deals with the pandemic and my relationship with my son and neighbors. The book begins with a sequence, His Own Hand, that won Dialogue’s Bodies of Christ contest, and ends with Holy Commerce, a section that considers aspects of living the Gospel in a beautiful but fallen world. But prayer, death, suffering, natural beauty—all ways of penetrating or thinning the veil—figure in poems throughout the book. Another way is art. Interrupted at the Crucifixion is a sequence of ekphrastic poems. Arranged in chronological order, they deal with suffering in art—suffering and trauma as themes, the suffering of the models, and the pathos and arrogance of the artists who want to depict “how a thin man of Adam / is altered by crucifixion” (“Léon Bonnat, Christ on the Cross”).

Once I was ambitious but lazy, little understanding how much effort is required to be merely competent in poetry; now I am industrious but disabused of any notions of grand success. Industry can do only so much. In sports, wrote Milosz, “a certain comfort with passivity allows the body to work in harmony. This is even more true in poetry; straining comes to nothing, for we receive the gift whether we are deserving of it or not” (“Ambition,” Milosz’s ABC’s, trans. M. G. Levine (FSG, 2001), 25). Now I try to approach the writing of poetry as a natural if important part of living. Sometimes I try a new plant in our garden, sometimes I learn how to write ballades, sestinas, and villanelles; Skating has one of each, as well as three sonnets and a double sonnet, rhyming quatrains, several poems in syllabics, one in trochaics, and the usual cargo of free verse.

I rarely have a good sense of my audience beyond those somehow incorporated into my sensibility—my father, my maternal grandmother and my first mother-in-law, Keats (“Ode to a Nightingale” is vividly present in “Gentile Bellini, John the Baptist”), and others. The best teacher I ever had, Arthur Henry King, wrote, “An important experience is an end in itself.” Writing poems is an important experience of my life, and perhaps one or two of my poems will offer such an experience to readers. King wrote: “If we come away from an experience and ask ourselves what it means or what it is all about, we are asking ourselves the wrong kind of question because what we have just experienced is what it is all about. An important experience is an end in itself. It isn’t something that is to prepare us for something else” (“Total Language,” Arm the Children (BYU Studies, 1998), 190).

I am deeply grateful to Patti who indulges my time at the keyboard with little reward beyond the experience offered by the poems. Skating Rough Ground acknowledges my “unpayable debts to the lord / of hellebore and dogwood and bleeding-heart” (“In my yard are henbit”) and to many more than I could name here:

Always carried—by loving wife,

quorums of doubting believers, siblings and friends,

even rank strangers—

so I learned grace. (“Your Graces and Your Gifts”)

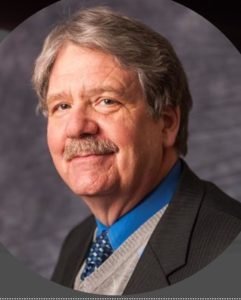

J. S. Absher (www.js-absher-poetry.com) remembers four of the six great grandparents that were living when he was born, lending him memories that go back to just after the Civil War. In a largely uneventful life, thirty years of it in the health insurance industry, he has been a missionary, offset printer, teller, janitor, project manager, director of ethics and compliance, records manager, editor, consultant, unit clerk in a hospital, and surveyor’s helper. Though a lazy student, he managed to get a B.A. in English from Brigham Young University and a PhD in 18th-century English Literature from Duke University, though it took the length of the Trojan War for him to finish the dissertation. He taught briefly at Southern Virginia University as an adjunct and once taught a class on the traditional ballad in Belize.

J. S. Absher (www.js-absher-poetry.com) remembers four of the six great grandparents that were living when he was born, lending him memories that go back to just after the Civil War. In a largely uneventful life, thirty years of it in the health insurance industry, he has been a missionary, offset printer, teller, janitor, project manager, director of ethics and compliance, records manager, editor, consultant, unit clerk in a hospital, and surveyor’s helper. Though a lazy student, he managed to get a B.A. in English from Brigham Young University and a PhD in 18th-century English Literature from Duke University, though it took the length of the Trojan War for him to finish the dissertation. He taught briefly at Southern Virginia University as an adjunct and once taught a class on the traditional ballad in Belize.

.

I just read Night Weather!

(It was excellent.)