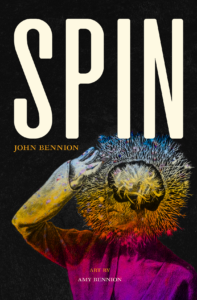

The AML Book Club will be discussing John Bennion’s experimental novel Spin on September 18, 7pm (Mountain). John will join us at 7:30 pm to answer questions about his work.

The AML Book Club will be discussing John Bennion’s experimental novel Spin on September 18, 7pm (Mountain). John will join us at 7:30 pm to answer questions about his work.

Our next Book Club will be a discussion of Noah Van Sciver’s graphic novels “One Dirty Tree” and “Joseph Smith and the Mormons” on October 16 at 7pm. Noah will be joining us for the discussion.

To prepare for the event, here is John’s post introducing the book. You can also read Theric Jepson’s review of the book, and the John’s AML Lifetime Achievement Award citation.

Lily knew her husband of three years was rich, powerful, and cunning, but he still surprises her when, after their divorce, he drains her bank accounts, turns her few friends against her, and gets custody of their baby, Anne. Lily tries ardent pleading, assertiveness, rage, dishonesty, bartering, manipulation, and appeal to authority, but nothing works. Faced with sudden homelessness and the knowledge she cannot outfox her ex and discover where he has hidden Anne, Lily turns to the irrational. She spins a wheel that she found in a thrift store, and this randomizing device leads her straight to Anne. She takes the child and runs. She spins again and again, staying off the grid and avoiding capture.

Like Lehi and his family, Lily trusts a device to guide her, in her case, the “Executive Decision Maker” that she finds in a thrift store. The spindle on the Liahona was powered by the Lehites’ faith in God, a physics beyond their understanding. Lily’s wheel is powered by an unlikely synthesis of will and chance. Counterpoint to the fictional wheel Lily bought is the one I own, a prank gift from a friend. As I wrote the first draft, I spun it when Lily needed to make a decision, so the wheel operates in both the dimensions.

Like Lehi and his family, Lily trusts a device to guide her, in her case, the “Executive Decision Maker” that she finds in a thrift store. The spindle on the Liahona was powered by the Lehites’ faith in God, a physics beyond their understanding. Lily’s wheel is powered by an unlikely synthesis of will and chance. Counterpoint to the fictional wheel Lily bought is the one I own, a prank gift from a friend. As I wrote the first draft, I spun it when Lily needed to make a decision, so the wheel operates in both the dimensions.

I am a fan of George Eliot’s novel Middlemarch, which Virginia Woolf wrote was the only novel in English for adults. It is a feminist novel describing the industrial town of Middlemarch and the surrounding estates. Set in the years just before the First Reform Bill in 1832, Eliot’s narrator describes the tensions as power begins to shift from the upper to the middle class. How does community survive through such an enormous transition? As well as considering the macrocosm of community, Middlemarch also explores the microcosm of individual behavior, largely through the story of several marriages, good and bad. At the center is Dorothea Brooke’s stifling first marriage and her hopefully successful second.

The United States doesn’t have a class system, but inequities are still high between rich and poor, men and women, and whites and people of color. Spin is an experiment in what might happen when a divorced woman falls from her husband’s level, wealthy upper middle class, to the level of a homeless person. I’m also a fan of Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles, the story of a woman who is raped before her marriage to another man and then is abandoned by that husband. She wanders Dorset trying to keep herself alive. What will a woman do when all her resources except for her own intelligence are taken from her? What does community mean to a homeless person?

Another aspect of Middlemarch that I admire is that Eliot’s narrator periodically digresses from the story to reflect on politics and marriage, philosophy and human perception. These riffs enhance the narrative rather than detract from it, and are similar to the perambulations of essayists during her time and now. As Lily tries to escape her husband and survive, I periodically essay on psychotherapy, perception of the Other, homelessness, probability theory, space-time, human volition, philosophy, literary criticism, the lore and science of love, visual art, and personal experience—also on beer making, First Peoples, Mobius bands, gangs, and cockroaches. Lily is an artist and her sketches populate the novel, drawn in this reality by my daughter Amy, who teaches art at the University of North Florida.

![]() I have no illusion that this collaboration ever rises to the level of Middlemarch and Tess. I would have to be completely out of touch with myself to think that. I can claim, however, that through studying Eliot and Hardy, I have come to have some of the same concerns. Is it a good novel? I don’t know. Try it out. Take it for a spin.

I have no illusion that this collaboration ever rises to the level of Middlemarch and Tess. I would have to be completely out of touch with myself to think that. I can claim, however, that through studying Eliot and Hardy, I have come to have some of the same concerns. Is it a good novel? I don’t know. Try it out. Take it for a spin.

![]()

![]() A native of the Utah desert, John Bennion has published a collection of

A native of the Utah desert, John Bennion has published a collection of ![]() short fiction, Breeding Leah and other Stories (Signature Books, 1991), and three novels other than Spin—Falling Toward Heaven (Signature Books, 2000), An Unarmed Woman (Signature Books, 2019), Ezekiel’s Third Wife (Roundfire Books, 2019). Another novel, Ruth at the End of the Earth is forthcoming next year from BCC Press. He has published short stories and essays in Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment, Hotel Amerika, Southwest Review, AWP Chronicle, Hobart, Palaver, High Country News, Utah Historical Quarterly, Journal of Mormon History, Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, Sunstone Magazine and others. He has retired from teaching creative writing in the English Department at Brigham Young University. For three decades he led outdoor writing programs that use the writing of personal essays to promote student growth. He has developed the Experiential Writing Project, sponsored by the Humanities College at BYU; this website provides training materials and other resources to experiential educators who use reflective writing in their programs. He is the recipient of the 2021 Association for Mormon Letters Lifetime Achievement Award. He lives in Provo with his wife, Karla, a writer and psychotherapist.

short fiction, Breeding Leah and other Stories (Signature Books, 1991), and three novels other than Spin—Falling Toward Heaven (Signature Books, 2000), An Unarmed Woman (Signature Books, 2019), Ezekiel’s Third Wife (Roundfire Books, 2019). Another novel, Ruth at the End of the Earth is forthcoming next year from BCC Press. He has published short stories and essays in Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment, Hotel Amerika, Southwest Review, AWP Chronicle, Hobart, Palaver, High Country News, Utah Historical Quarterly, Journal of Mormon History, Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, Sunstone Magazine and others. He has retired from teaching creative writing in the English Department at Brigham Young University. For three decades he led outdoor writing programs that use the writing of personal essays to promote student growth. He has developed the Experiential Writing Project, sponsored by the Humanities College at BYU; this website provides training materials and other resources to experiential educators who use reflective writing in their programs. He is the recipient of the 2021 Association for Mormon Letters Lifetime Achievement Award. He lives in Provo with his wife, Karla, a writer and psychotherapist.