By Michael Hicks

Monday, September 26, 2022: an anniversary that probably escaped your attention. That’s okay. We all have enough on our minds—hurricanes, pandemics, scandals, you name it. But that day was the 25thanniversary of the passing of one of Mormonism’s most estimable men of letters: Samuel Woolley Taylor. Noticing that anniversary, I emailed Andrew Hall and volunteered to write a piece on Taylor for this website. Now I’m feeling sheepish. I’ve never read any of Taylor’s novels, not even  Heaven Knows Why! (1948), which more than one friend of mine regards as the funniest Mormon novel. I’ve never read any of his short stories, even though a signed collection of them beams at me from the shelf. I’ve done no biographical research on him, never interviewed him or anyone in his literary circle. Indeed, I never met the man, even though for years he lived just a few miles from my house. But—hear me out—he’s probably the most important voice in my Mormon upbringing. In fact, it’s fair to say that when I was baptized in December 1973, it was into the Church of Jesus Christ of Sam-Taylor Saints.

Heaven Knows Why! (1948), which more than one friend of mine regards as the funniest Mormon novel. I’ve never read any of his short stories, even though a signed collection of them beams at me from the shelf. I’ve done no biographical research on him, never interviewed him or anyone in his literary circle. Indeed, I never met the man, even though for years he lived just a few miles from my house. But—hear me out—he’s probably the most important voice in my Mormon upbringing. In fact, it’s fair to say that when I was baptized in December 1973, it was into the Church of Jesus Christ of Sam-Taylor Saints.

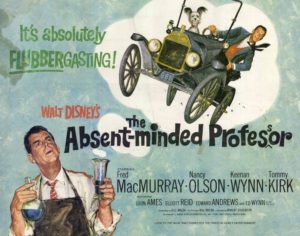

That baptism was in Menlo Park, right next to Stanford where Dialogue was born, right below Redwood City, where Sam lived, and close to Los Altos, where I lived. Although I had a “testimony” of my new church, what we all had steaming in our blood was the same testimony that migrants to the West Coast felt for over a century: the San Francisco Bay Area was its own kind of Promised Land, from its sea air to its sequoias, from Jack London to City Lights Books, from Joan Baez to the Grateful Dead, and on and on, all laid out in a dewy, temperate climate with fertile soil underfoot. I had no idea who Sam Taylor was, although as a kid I loved two Disney movies based on the “Flubber” stories he’d written. Now, as a Mormon convert at 17, I heard in hushed tones about a book called Nightfall at Nauvoo, whose title seemed to foreshadow the darkness some people thought lurked between its covers. Was the book accurate? Was it fair? Some of my friends called it anti-Mormon, others called it genius. I bought a paperback copy and with the opening sentence of its first chapter, “The Phantom City,” I was a fish on the line. “Steam from the foot-bath coiled upward around the frail young man at the writing desk, mingling with the sharp aroma of the rum-soaked towel around his head and the odor of the oil lamp.” Talk about “first visions.” I was having one, transported back to 1840s Illinois in thirty-six words.

That baptism was in Menlo Park, right next to Stanford where Dialogue was born, right below Redwood City, where Sam lived, and close to Los Altos, where I lived. Although I had a “testimony” of my new church, what we all had steaming in our blood was the same testimony that migrants to the West Coast felt for over a century: the San Francisco Bay Area was its own kind of Promised Land, from its sea air to its sequoias, from Jack London to City Lights Books, from Joan Baez to the Grateful Dead, and on and on, all laid out in a dewy, temperate climate with fertile soil underfoot. I had no idea who Sam Taylor was, although as a kid I loved two Disney movies based on the “Flubber” stories he’d written. Now, as a Mormon convert at 17, I heard in hushed tones about a book called Nightfall at Nauvoo, whose title seemed to foreshadow the darkness some people thought lurked between its covers. Was the book accurate? Was it fair? Some of my friends called it anti-Mormon, others called it genius. I bought a paperback copy and with the opening sentence of its first chapter, “The Phantom City,” I was a fish on the line. “Steam from the foot-bath coiled upward around the frail young man at the writing desk, mingling with the sharp aroma of the rum-soaked towel around his head and the odor of the oil lamp.” Talk about “first visions.” I was having one, transported back to 1840s Illinois in thirty-six words.

That was how Sam wrote: like an old-school pulp author who knew how to churn out the butter of slick, tasty prose. But he was bilingual, too—or at least could slide swiftly from one prosy dialect to another. Look no further than the last line of his preface to the memoir of his mom and dad—exiled apostle John W. Taylor—Family Kingdom, published five years before I was born but reissued right after my baptism. “This book is not intended to be representative of Mormons or Mormonism. It is the story of a girl who hitched a wild ride for time and eternity with a human rocket.” From schoolroom to barroom in two sentences.

That was how Sam wrote: like an old-school pulp author who knew how to churn out the butter of slick, tasty prose. But he was bilingual, too—or at least could slide swiftly from one prosy dialect to another. Look no further than the last line of his preface to the memoir of his mom and dad—exiled apostle John W. Taylor—Family Kingdom, published five years before I was born but reissued right after my baptism. “This book is not intended to be representative of Mormons or Mormonism. It is the story of a girl who hitched a wild ride for time and eternity with a human rocket.” From schoolroom to barroom in two sentences.

Still, he could blend these dialects into a plainspoken hybrid that I, at least, could not resist. As in, say, the majesty of Nightfall‘s closing passage on the exodus from Illinois:

With them they took cuttings of the trees, roots of shrubs, bulbs and vegetable seeds, wheat and corn from Nauvoo, the spark of life that would be planted in the new land in the wilderness.

What they left behind were soil, brick, timber, the empty shells of houses and stores, municipal buildings and former church edifices. But the living city—the people and the records, the seeds and sprouts of vegetable life, the livestock, the living faith of the Peculiar People—this was all enroute across the frozen continent, headed for an unknown destination, some place where they dreamed of finding peace, and here they would restore Nauvoo, intact, in the never-never land.

Nauvoo wasn’t being abandoned; it simply was being moved to another location.

What reshaped my teenage life, though, and plowed open my career as both a Mormon and a historian was reading his annotated bibliography to Nightfall at Nauvoo. Here, from one of the smartest brokers around, was the backstage pass to the Mormon intelligentsia, from the Church Historian’s Office to Utah Lighthouse Ministry, all couched in his sly, nudge-in-the-ribs polemics.

The introduction to the bibliography throws down the anti-academic gauntlet. “I have looked at Nauvoo as a writer, not as a historian. There is a difference. A writer lives by ideas, while a historian isn’t allowed to have one.” He takes Thomas Kane’s The Mormons as a model. It’s “a gem of Mormon literature (a field containing precious few jewels), but historians reject it because of the very quality that makes it great: it ignores nit-picking detail to achieve a powerful statement of essential truth. And this is what I prize above all.”

Not “prize alone,” though, just “above all.” He did pursue facts, even “details,” and was a tiger against anyone trying to hide or paint over the uncomfortable ones. Thus, he turned a rogue’s gallery of alleged anti-Mormons into proto-investigative journalists—T. B. H. Stenhouse or even Edward Bonney in the nineteenth century and, above all, Gerald and Sandra Tanner in the twentieth. (His longest annotation in Nightfall is for the Tanners’ Mormonism: Shadow or Reality?) These and others on the wrong side of the Union Pacific tracks wrote heroically, right alongside Mormon defender of the faith B. H. Roberts, whom Taylor praised for his “courageous battle against censorship.” Taylor’s verbal gunfire against attempts to soak-and-rinse Mormon history was not to discount, say, fervid Mormon memoirist Parley P. Pratt, let alone the church’s Faith-Promoting Stories series, which he called “among the very best products of the church’s internal literature, [which] do more than a dozen university theses to reveal the character and incandescent faith of the early Mormons.” That’s because, for him, stories well told always cover a multitude of sins, whichever side you’re on. Nevertheless, Taylor’s unspoken maxim was: don’t undervalue the chips on people’s shoulders.

I’d have loved to read a Sam Taylor biography of Brigham Young. But Taylor had a family errand to run: The Kingdom Or Nothing: The Life of John Taylor, Militant Mormon (1976), which lionized his grandfather—Brigham’s successor as church president—while honoring Sam’s brother Raymond, who did the research for the book but was no writer. (“Except for circumstance, it would have been Raymond’s book.”) I had recently lapped up B. H. Roberts’s Life of John Taylor but couldn’t wait to get my hands on this one, which I expected would be a Taylorized, intimate, gossipy, guerilla-style yet ultra-reverent treatment—at least as I’d come to define “reverent,” which included allegiance to “essential truth.” It was just what I expected. The opening chapter, “The Strange Death of Brigham Young,” begins with the words “A blue-bottle fly buzzed in the muggy heat of the Church Office Building as John Taylor worked at the pile of old ledgers.” I knew I was reading more of the strange bringing-to-life of Mormon history.

I’d have loved to read a Sam Taylor biography of Brigham Young. But Taylor had a family errand to run: The Kingdom Or Nothing: The Life of John Taylor, Militant Mormon (1976), which lionized his grandfather—Brigham’s successor as church president—while honoring Sam’s brother Raymond, who did the research for the book but was no writer. (“Except for circumstance, it would have been Raymond’s book.”) I had recently lapped up B. H. Roberts’s Life of John Taylor but couldn’t wait to get my hands on this one, which I expected would be a Taylorized, intimate, gossipy, guerilla-style yet ultra-reverent treatment—at least as I’d come to define “reverent,” which included allegiance to “essential truth.” It was just what I expected. The opening chapter, “The Strange Death of Brigham Young,” begins with the words “A blue-bottle fly buzzed in the muggy heat of the Church Office Building as John Taylor worked at the pile of old ledgers.” I knew I was reading more of the strange bringing-to-life of Mormon history.

In 1978 I enrolled at BYU to complete my bachelor’s degree in music. As if anointing my entry into this new realm of Mormondom, Taylor’s next “Mormon” book suddenly came off the presses: Rocky Mountain Empire: The Latter-day Saints Today, the third in what Macmillan’s jacket copy called “episodes in [Taylor’s] Mormon chronicle.” Sam’s Restored Curmudgeonism was in full bloom—raucous, untethered, and brilliant. I loved every syllable of it. Here was a voice in the wilderness, but less a Charlton Heston-style Moses than a guard dog barking from far away, warning of trouble ahead.

In 1978 I enrolled at BYU to complete my bachelor’s degree in music. As if anointing my entry into this new realm of Mormondom, Taylor’s next “Mormon” book suddenly came off the presses: Rocky Mountain Empire: The Latter-day Saints Today, the third in what Macmillan’s jacket copy called “episodes in [Taylor’s] Mormon chronicle.” Sam’s Restored Curmudgeonism was in full bloom—raucous, untethered, and brilliant. I loved every syllable of it. Here was a voice in the wilderness, but less a Charlton Heston-style Moses than a guard dog barking from far away, warning of trouble ahead.

The first ten chapters (under the heading “Latter-day Laocoön“) stitched a quilt of narratives surrounding the Smoot Hearings and the preservation of polygamy as lore via its (alleged) eradication in practice. That made the first two-thirds of the book an aerial tour of the landscape Taylor had mapped from the ground up in Family Kingdom twenty-seven years earlier. The book’s final six chapters, though, met me where I now lived: a (very) stained-glass depiction of “Happy Valley,” the interior and exterior environs of BYU as he’d lived it on site. The book ended with nuggets from his later life in the San Francisco Stake, especially among what he called the “Middlefield Roaders.” Again, it was as if the book were dropped on my doorstep. When I was baptized, I lived two blocks from Middlefield Road.

By 1984 I was finishing my doctorate in music at University of Illinois and Taylor was finishing the next two volumes of his “Mormon chronicle,” The John Taylor Papers, a documentary set he’d assembled with Raymond and published himself via the “Taylor Trust.” I sent him a check for a copy, along with a fan letter. I got the books, both signed, planted them on my shelf, and, unable to land an academic job, moved with Pam and our two kids from Illinois back to Mountain View, a few blocks from where I’d gone to high school. A year later, almost miraculously, I was hired onto the BYU music faculty where I began work on my first book, Mormonism and Music: A History. I gradually lost track of Sam and whatever work he did from then on.

By 1984 I was finishing my doctorate in music at University of Illinois and Taylor was finishing the next two volumes of his “Mormon chronicle,” The John Taylor Papers, a documentary set he’d assembled with Raymond and published himself via the “Taylor Trust.” I sent him a check for a copy, along with a fan letter. I got the books, both signed, planted them on my shelf, and, unable to land an academic job, moved with Pam and our two kids from Illinois back to Mountain View, a few blocks from where I’d gone to high school. A year later, almost miraculously, I was hired onto the BYU music faculty where I began work on my first book, Mormonism and Music: A History. I gradually lost track of Sam and whatever work he did from then on.

By the time he died in 1997, I was a full-fledged Professor of Music cataloguing my own mental repertoire of Happy Valley quirks and deformities. The news of Sam’s passing dribbled through the grapevine, I heard about it and mourned, grateful for the man’s place in bank-shotting me into my career and, by example, whatever authorial craft I’d achieved. And that was that.

So I thought.

Ten years later my family and I were visiting my mom in Los Altos. We spent an afternoon in Palo Alto and, when they went off for a late lunch, I said I’d catch up with them. I had another pilgrimage: the legendary Bell’s Books, around the corner from the diner. As I browsed their religion section, two Mormon books caught my eye: John Henry Evans’s Joseph Smith: An American Prophet and John Widtsoe’s Joseph Smith: Seeker After Truth, Prophet of God. Both of them had stickers with the previous owner’s name and address pasted on their flyleaves.

Samuel W. Taylor

1954 Stockbridge Avenue

Redwood City, California

The half-title page of the Widtsoe also had this handwritten inscription in red pen:

Samuel W. Taylor

Redwood City

26 Sept 52

Underlining and marginalia from the same pen were scattered throughout its pages—probably why the book (priced at $20) had gotten no buyers so far. Condition is everything, they say. But the sticker and markings in this one—and similar ones in the Evans book—were the very condition that made my heartbeat quicken as I hauled them to the cash register and plopped down my Visa card. Worn commonplaces that general buyers might snub were holy relics to me: two of the books Sam read and marked up on the way to Nightfall at Nauvoo.

They talk about “tender mercies.” Maybe that was one of them. But ten years later, its sequel arrived. In October 2017, almost twenty years to the day since Sam’s passing, I went to the estate sale of Grenade Curran in Orem, Utah. There on the second floor of Curran’s house, sandwiched between Disney scrapbooks and cowboy clothing racks, I found a box of original 1960s film and television treatments for a company Curran had once co-owned, Inter-American Film Productions, Inc. Some of the treatments were carbon copies, some original typescripts, and, among the pile of twenty or so, were four by Samuel W. Taylor. One was for another Disney-style fantasy story (“Gorilla Go Home”), one was for a television series based on Vardis Fisher’s multi-volume Testament of Man, another was for a series called “Deseret,” and yes, one, in its original typescript with penciled corrections, was for a series called “Nauvoo.” I bought them all, two bucks apiece.

They talk about “tender mercies.” Maybe that was one of them. But ten years later, its sequel arrived. In October 2017, almost twenty years to the day since Sam’s passing, I went to the estate sale of Grenade Curran in Orem, Utah. There on the second floor of Curran’s house, sandwiched between Disney scrapbooks and cowboy clothing racks, I found a box of original 1960s film and television treatments for a company Curran had once co-owned, Inter-American Film Productions, Inc. Some of the treatments were carbon copies, some original typescripts, and, among the pile of twenty or so, were four by Samuel W. Taylor. One was for another Disney-style fantasy story (“Gorilla Go Home”), one was for a television series based on Vardis Fisher’s multi-volume Testament of Man, another was for a series called “Deseret,” and yes, one, in its original typescript with penciled corrections, was for a series called “Nauvoo.” I bought them all, two bucks apiece.

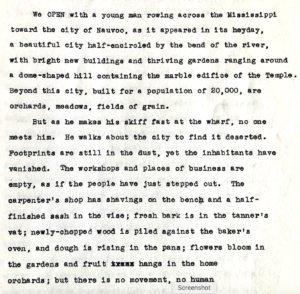

The 32-page Nauvoo treatment is plain and workmanlike but crisp as crunching snow. Consider its descriptive first paragraphs.

Unlike Nightfall‘s brooding on a lone figure in the dark, this tale opens as a Twilight Zone-ish encounter with a deserted city. One feels at once that Taylor knew television the way he knew books. He could romance either one with the keystrokes of his clanking manual typewriter.

![]() Leafing through those handmade artifacts the last few years keeps me in touch with his ghost. It’s a ghost that haunts me with the nerve of the working writer hustling for a paycheck—gauging how much per word, yet always hunting down the right word, syllable by syllable, laying down footprints in a reader’s mind. It haunts me with the unsteady line between reverence and cheekiness that threads through all his Mormon work. And it haunts me with a voice soaked in the gene pool of a people, which is one I don’t share and never can.

Leafing through those handmade artifacts the last few years keeps me in touch with his ghost. It’s a ghost that haunts me with the nerve of the working writer hustling for a paycheck—gauging how much per word, yet always hunting down the right word, syllable by syllable, laying down footprints in a reader’s mind. It haunts me with the unsteady line between reverence and cheekiness that threads through all his Mormon work. And it haunts me with a voice soaked in the gene pool of a people, which is one I don’t share and never can.

At the same time, in laying down these thoughts I see my own work through the lens of so many Tayloresque lessons-in-the-form-of-questions. Lucky me, one question has faded into the sunset of my 35-year-long BYU career: how can I tell tales out of school and keep working for the school? But other questions linger till the day I die—or stop writing, hopefully the same day. How can I shave my prose without making it bleed? How can I write history without a blizzard of footnotes burying the story? And the question we all face every day: how can I be fearless without being reckless?

Michael Hicks is the author of the memoir, Wineskin: Freakin’ Jesus in the ‘60s and ‘70s, which will be published by Signature Books in November. The composer, poet, and author recently retired as Professor of Music at Brigham Young University. He is the former editor of the journal American Music (2007–2010), and author of The Mormon Tabernacle Choir: A Biography (2015). He has won AML Awards for Mormonism and Music: A History (Criticism, 1989), The Street-Legal Version of Mormon’s Book (Adaption, 2012), and “The Second Coming of Mormon Music” (Criticism, 2017). He also received a notable mention for the book Do Clouds Rest? Dementiadventures with Mom (Creative Nonfiction, 2017) and was a finalist for his collection of essays Spencer Kimball’s Record Collection: Essays on Mormon Music (Criticism, 2020).

What a fascinating story! I agree with your friend who said “Heaven Knows Why” is the great Mormon humor novel. And “Nightfall at Nauvoo” is so evocative, his words are still the way I imagine the city. Now I am excited to read “Family Kingdom.”

It sounds like he wrote a ton of pulp and “slick” (Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s, etc) stories in the 30s and 40s, probably a lot of them under pseudonyms. There is work to be done there!

Here is a really good biographical article, which includes a lot about both his literary and personal life.

“Samuel W. Taylor: Talented Native Son.” By Jean R. Paulson.

Utah Historical Quarterly, 67:3, 1999.

https://issuu.com/utah10/docs/uhq_volume67_1999_number3/s/163296

Jean’s is a warmly illuminating article. Thanks for providing the link. I hope readers will check it out.

This is a wonderful reflection Mike, thank you for it. I have long suspected that Taylor might be our most fascinating literary figure, hiding in plain sight and wearing historians clothes. He definitely needs, and deserves, further study.

I heard him speak at a Sunstone Symposium in, I think, 1996, right before he died. I didn’t know much about him then, so I didn’t know what to expect. He stood up at the podium and said, “I’m going to tell you the story of how Joseph F. Smith excommunicated my father and lied about it under oath to save Reed Smoot’s Senate seat.” All of which he proceeded to do, just as bluntly as promised.

As a fiction writer, he was amazing. He wrote a number of hard-boiled mystery novels, including particularly naughty one, Brenda, under the pseudonym Lehi Zane. He wrote short stories for some of the largest publications in the county. And Heaven Knows Why is indeed the funniest Mormon novel ever. And also one of the most read. In its original version–serialized in Colliers Magazine as “The Mysterious Way,” it had around 6 million readers (or, at least, subscribed purchasers).

Anyway, thanks for this wonderful reflection. I can’t wait to read Wineskin.

.

Thanks so much for this, Michael. I’m the opposite of you—except for some (brilliant and sharp) essays and letters in Dialogue, all I’ve read of his is his fiction. But that one-two has been enough to make me a fan. I’ve never picked up any of these nonfiction (lessfiction) books, but now I’m feeling the lack.

Ah, if we’d known who we will wish we’d’ve talked to when we we young when we were young!

Such a great tribute and article.