“Flaming Breath of Truth”: Search of Mormon Author

By Maria Hyde

The Daily Universe, December 17, 1969

[Thank you to Rachel Helps, who found this article in the Victor Purdy Papers in the BYU library archives. It is an interesting snapshot at the feelings of people involved in Mormon literature in 1969, three years after the establishment of Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, which is often seen as the beginning of the modern era of Mormon literature, but some years before the creation of the Mormon literature class at BYU, and the creation of the Association for Mormon Letters in 1976. Note the mix of older and younger authors and academics, whose interesting careers are discussed in the footnotes.]

[Thank you to Rachel Helps, who found this article in the Victor Purdy Papers in the BYU library archives. It is an interesting snapshot at the feelings of people involved in Mormon literature in 1969, three years after the establishment of Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, which is often seen as the beginning of the modern era of Mormon literature, but some years before the creation of the Mormon literature class at BYU, and the creation of the Association for Mormon Letters in 1976. Note the mix of older and younger authors and academics, whose interesting careers are discussed in the footnotes.]

“Often while being riddled by the criticism of a worn-out world he knows to be the flaming breath of truth is wasted wind. He shrouds the fact in form and so mirrors life in fiction.”

“Often while being riddled by the criticism of a worn-out world he knows to be the flaming breath of truth is wasted wind. He shrouds the fact in form and so mirrors life in fiction.”

Prose that is poetry from Dennis Drake,[1] a BYU English graduate assistant, that expresses the problem facing the Mormon author today—lack of acceptance when he utters “the flaming breath of truth,” or fear to breathe it in the first place.

Dr. John S. Harris,[2] who teaches English, met this problem with his poem, “The Unhobbled Mare,” that explored a relationship between an insensitive pioneer wife and her frustrated husband. Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, the magazine that published the poem, received letters of protest and a subscription cancellation from offended members.

Christie Lund Coles,[3] a Provo poet of verse published everywhere from the Chicago Tribune to the Relief Society Magazine, has produced a polygamy play “The Red Plush Parlor”. But she hesitates to publish her last play on the subject. It raises questions, she claims that people may object to.[4]

Ann Doty,[5] copy editor of Wye magazine, tells of a short story about a missionary torn with doubts that she wrote for a BYU creative writing class. “I got an A on the story” she remembers, and a note saying, “I don’t think you would get this published.”

What to Write?

As Mormon literature begins to emerge, the Mormon author finds himself in a quandary about what to write about. Should he explore the conflicts, the trials of Mormonism? Should he merely deal with life? Or should he, aware of his Mormon background and beliefs, concentrate his talents on literature fit for the Era, the Instructor, or the Relief Society Magazine?

The overwhelming answer to the final question seems to be no. “You will never achieve universal connotations if you limit yourself to the Relief Society Magazine, Ann feels.

Mrs. Coles is a regular contributor to the magazine that she defends as a fine publisher of “lyric poetry.” Yet, she prides herself that she is able to write “contemporary” verse worthy enough for Dialogue, and feels she must write both types to maintain versatility as a writer.

But Drake feels, “All of us have an obligation to lend out our minds, to voice our highest thoughts.” And often those “highest thoughts” cannot find expression simply in the Era [and] Instructor format.[6]

As Edward Geary,[7] a member of the Dialogue board of directors points out, “great literature almost never has an ostensible purpose,” and too often the didactic, moralistic tone of church publications does not attract authors intent on establishing a literature worthy of the appellation.

Didacticism, Alienation

But avoiding didacticism is a real problem facing the Mormon writer with the best of intentions. Carol Lynn Pearson,[8] the successful author of Beginnings, an oft-quoted collection of verse, speaks of the “pragmatic” attitude Mormons often have toward life. “When you have a thought that’s moralistic, you’ve got to figure out a way to dress it so that it’s not offensive.”

There is not only the offense toward the content of literature to avoid, there is the offense toward sensitive members to take into consideration. Sometimes, one offense can rarely be avoided without committing the other.

“Mormonism will never be the spontaneous augur for creative incentive,” feels Richard Parkinson, a writing senior. “You have to be able to crawl inside the skin of other people,” he feels. “Mormons are often alienated.”

This alienation often results from what Ann coins as “a separator of added knowledge” that “acts as an etherizer. It makes us assured. We think we know all the answers and so we don’t have to question and grope and search.”

“We should have added sensitivity added desire to get inside the man and express what we find,” she urges. Dr. Richard Cracroft[9] feels that the Mormon “eternity to eternity” view of life instead of the usual “birth to death” attitude can give authors the “added sensitivity” they need.

Mrs. Pearson, who writes for the BYU Motion Picture Studios, finds that such criticism are flung at film scripts that are called “Pollyanna productions,” “tied with a blue ribbon.” But she mentions the myriad of hands the script must pass through for approval. “They’ve got to be careful,” she says. “People see the films and say ‘ah hah, this is church doctrine because it’s got the stamp of the general authorities on it.” However, she mentions that not everyone has to go [to] the General Authorities for approval.

Of the scattered literature that has been written about or by Mormons, none, however scathing, has incurred official censure from the Church.

Self-Imposed

Most censorship is “self-imposed,” believes Dr. Cracroft. He tells of a story about drugs that was submitted to the Y [Wye] magazine that he advises. “My artistic sense said, ‘This is valuable,’ but my sense of Mormonism said we have another obligation to be missionaries.”

Geary agrees that censorship is often self-imposed, but he feels that it’s through fear of social pressure, “what the ward and bishop will think.” He emphasized that “we need to throw out the attitude that one kind of literature converts and that another kind doesn’t.” He advocates that one has to make “an artistic judgment” of the literature before it is condemned as dangerous to testimonies.

“Taste and Restraint”

Yet, he feels that the church has “no obligation to coddle its destructive artists.” Mrs. Coles agrees, feeling that touchy subjects must be handled with “taste and restraint.” She cites this as the reason why “The Red Plush Parlor” raised few questions. She refused to sell the play to Hollywood for fear her “taste and restraint” would be shattered. “Everyone respects a people who respect what they’re supposed to.”

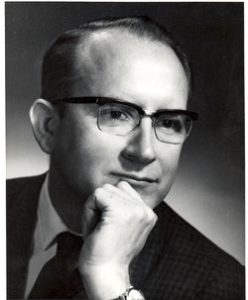

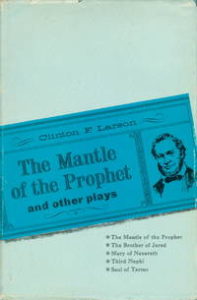

The prolific Dr. Clinton Larsen[10] of the English department who has published quantities of plays and poems and has just recently finished an opera based on the life of Joseph Smith, feels the secret lies in reserving judgement.

He speaks of his poem, “Homestead in Idaho” that tells of a pioneer mother alone with her children for the winter, who is fatally bitten by a rattlesnake. Before she dies, she kills her children to save them from slow starvation.

His “taste and restraint” device was not to “interpret on a doctrinal level.” To do so would be to stray from his purpose to “serve experience” as an author.

With the hope to serve experience in mind, many Mormon authors refuse to turn their pack on problems or unanswered questions within the church. “Good literature is the result of realizing and resolving conflict,” Ann believes.

Loftier Purpose

Rather than exploiting controversial topic for a “thrill” or “shock literature,” Mormon authors see a loftier purpose.

“How in the world can we help the sinner if we have no idea of the problems he’s going through?” questions Dr. Neal Lambert of the English Department.[11] Proposing that authors should tap unanswered questions such as the Negro or the unmarried older woman, Dr. Lambert feels, “Even if we don’t have the answer yet, we can be sympathetic. When we ourselves can get to the point where we can have sympathy and understanding, maybe then the answer will come.”

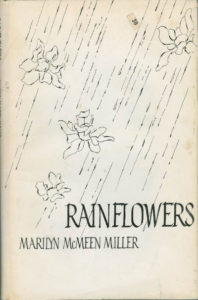

Marilyn Miller,[12] author of “Rainflowers” currently sold in the Bookstore, has just finished a novel about the Mormon handcart pioneers, but she rarely mentions that her characters are Mormons. As most authors, she is acutely aware of the lack of quality that results from constant “footnoting” of explanations of the faith.

However, she feels that her approach can “help build the kingdom of God. She tries to “preach it by not preaching it,” by “telling of things that touch everybody’s heart.” Of her characters she wants her readers to say, “Ah, they’re human beings, but they have so much faith and courage, it must be their religion.”

Her method echoes Dr. Larsen’s firm belief that “Jesus is the Christ” that diffuses his highly successful writing. Such an approach may conciliate didactic and good literature. As Dr. Lambert points out, some of the world’s greatest literature has been an “affirmation of the faith” that succeeded without didactic moralizing.

Mrs. Miller adds another concept to Mormon literature. “Writing is creating a little world,” she says, “and trying to keep everyone in character. A book is another world, and we as Mormons will someday be creating worlds. Here we have the opportunity to practice.”

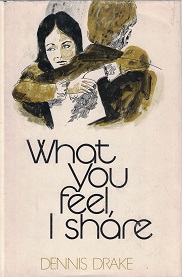

[1] Dennis Drake, the BYU English graduate assistant, had several poems published in 1968-1974, including poems in the Improvement Era,Dialogue, and in the 1974 Cracroft and Lambert-edited Mormon literature anthology, A Believing People. Bookcraft published a book of his poems, What You Feel, I Share, in 1971. Mary Bradford gave it a middling review in Dialogue. He contributed a personal essay, “And We Were Young,” to Dialogue in 1978, and a poem to the Ensign in 1982. That is the last published work of his that I have found.

[1] Dennis Drake, the BYU English graduate assistant, had several poems published in 1968-1974, including poems in the Improvement Era,Dialogue, and in the 1974 Cracroft and Lambert-edited Mormon literature anthology, A Believing People. Bookcraft published a book of his poems, What You Feel, I Share, in 1971. Mary Bradford gave it a middling review in Dialogue. He contributed a personal essay, “And We Were Young,” to Dialogue in 1978, and a poem to the Ensign in 1982. That is the last published work of his that I have found.

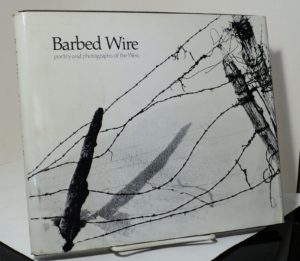

[2] John S. (Sterling) Harris, 1929-2013. BYU English Department faculty member (1963-1994), poet, and teacher of technical writing. He had two poetry collections published, Barbed Wire (BYU Press, 1974) and Second Crop (BYU Studies, 1996).

In his review of Barbed Wire, Ed Geary said his poems told stories of, “village society peopled by mischievous Jack Mormons, water-stealing high councilmen, and eccentric farmers who give their domestic animals a name and a blessing.” The encounters in Harris’s poems often have sexual elements, as mentioned in the BYU Universe article. Geary wrote, [the poem] “The Unhobbled Mare” was omitted from this volume because some administrators at Brigham Young University found it distasteful, and “Fallow” narrowly escaped the same fate. Clinton Larson has been faced with similar problems on occasion. It is unfortunate that these narrow attitudes persist . . . There is a good deal of loose talk at Brigham Young University about the emergence of “a great Mormon literature” and of Mormon writers to rival Goethe and Dante and Shakespeare. It is ironic that if a Mormon Dante or Shakespeare did happen to come along his works could not be published without bowdlerization by the BYU Press. It is also ironic that Harris’s most shocking poems escaped censorship, apparently because the censors did not understand them. For example, “First Spring Ride” tells of a lonely woman, filled with an inexplicable restlessness in early spring, who tempts her winter-wild horse into coming near enough that she can vault onto his back. She clings there for a ride which is described in increasingly obvious sexual terms.”

In his review of Barbed Wire, Ed Geary said his poems told stories of, “village society peopled by mischievous Jack Mormons, water-stealing high councilmen, and eccentric farmers who give their domestic animals a name and a blessing.” The encounters in Harris’s poems often have sexual elements, as mentioned in the BYU Universe article. Geary wrote, [the poem] “The Unhobbled Mare” was omitted from this volume because some administrators at Brigham Young University found it distasteful, and “Fallow” narrowly escaped the same fate. Clinton Larson has been faced with similar problems on occasion. It is unfortunate that these narrow attitudes persist . . . There is a good deal of loose talk at Brigham Young University about the emergence of “a great Mormon literature” and of Mormon writers to rival Goethe and Dante and Shakespeare. It is ironic that if a Mormon Dante or Shakespeare did happen to come along his works could not be published without bowdlerization by the BYU Press. It is also ironic that Harris’s most shocking poems escaped censorship, apparently because the censors did not understand them. For example, “First Spring Ride” tells of a lonely woman, filled with an inexplicable restlessness in early spring, who tempts her winter-wild horse into coming near enough that she can vault onto his back. She clings there for a ride which is described in increasingly obvious sexual terms.”

Harris built and piloted his own 200-miles per hour experimental airplane, which crashed in 1989, leaving him in great pain for the rest of his life, even though he returned to teaching in 1990. “Risk and Terror”, a personal essay given at the 1992 AML Conference, describes the experience, and the roles of free agency and risk in life.

Harris built and piloted his own 200-miles per hour experimental airplane, which crashed in 1989, leaving him in great pain for the rest of his life, even though he returned to teaching in 1990. “Risk and Terror”, a personal essay given at the 1992 AML Conference, describes the experience, and the roles of free agency and risk in life.

It is easy to confuse John S. Harris with John B. Harris (1928-2012), another BYU English professor who was nearly the same age.

[3] Christie Lund Coles (1906-1991). (From the Mormon Literature Database): “Coles was born in Salina, Utah, in 1906 but had resided many years in Provo, Utah, until her death in 1991, where she was a housewife and a free-lance writer. Widely published, Mrs. Coles has poems in such periodicals as Dialogue, BYU Studies, Western Humanities Review, Saturday Review, Ladies’ Home Journal, McCalls, Saturday Evening Post, the New York Times, the New York Herald-Tribune, and the LDS Church Magazines. She has published three volumes of verse: Legacy (1958), Some Spring Returning (1958), and Speak to Me (1970). Mrs. Coles wrote plays, short stories, and poems which won numerous contests. She has served as president of the League of Utah Writers, State fine arts chairman for the State Federation of Womens Clubs, and for the Women’s Council of Provo. An active member of the LDS Church, she served in the Relief Society, Primary and Young Women’s programs. She won many state and national contests, including the Eliza R. Snow Poetry contest. Member of the Sonneteers, and Fine Arts clubs.”

[3] Christie Lund Coles (1906-1991). (From the Mormon Literature Database): “Coles was born in Salina, Utah, in 1906 but had resided many years in Provo, Utah, until her death in 1991, where she was a housewife and a free-lance writer. Widely published, Mrs. Coles has poems in such periodicals as Dialogue, BYU Studies, Western Humanities Review, Saturday Review, Ladies’ Home Journal, McCalls, Saturday Evening Post, the New York Times, the New York Herald-Tribune, and the LDS Church Magazines. She has published three volumes of verse: Legacy (1958), Some Spring Returning (1958), and Speak to Me (1970). Mrs. Coles wrote plays, short stories, and poems which won numerous contests. She has served as president of the League of Utah Writers, State fine arts chairman for the State Federation of Womens Clubs, and for the Women’s Council of Provo. An active member of the LDS Church, she served in the Relief Society, Primary and Young Women’s programs. She won many state and national contests, including the Eliza R. Snow Poetry contest. Member of the Sonneteers, and Fine Arts clubs.”

Some of her poems appeared in Utah Sings, a 1942 poetry anthology. The introduction to Coles’ work read, “She has a tender, feminine touch. She has a facility of expression and fineness of feeling that rank her among the finest women of the state and Western America. A plaintive note runs throughout most of her poems which mellows them and makes them seem like jewels softened by tears.”

One poem, “Modern Christmas,” appeared on a full page in McCall’s, Dec. 1959. It called for a reconciliation between the star of Jesus and Sputnik of communism. That poem appeared in Cracroft and Lambert’s A Believing People.

[4] Christie Lund Coles’ The Red Plush Parlor, a musical comedy about polygamy, with music by Larry Bastian, was produced at BYU (1966, directed by Lael Woodbury), The Springville Art Theater (1968), and the Valley Center Theater (1976). In a Springville newspaper in 1968, she defended the play thusly, “Some will ask, ‘Why this subject? Why this long-hushed theme?’ Well, first, because it is a part of the LDS heritage as well as its history, for all to read. Through silence and inuendo, it has become something almost to be ashamed of, while in truth it was not. In the play I give the best and I think the most authentic reason for the practice of polygamy: That all the laws and ordinances of the original church should he restored in the latter days. It was not dark and ugly except as men made it so. It had its light and good side, as well as its problems. These I have tried to show in an entertaining fashion. Compared to society today, it is almost purity itself.”

The Red Plush Parlor, along with her 1968 play The Brothers (about Joseph and Hyrum Smith), are available through Leicester Bay Theatricals.

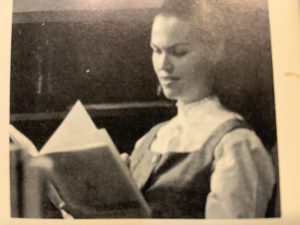

[5] Ann Doty (1948-1971). A BYU English student from Logandale, Nevada, who was the editor of Wye magazine, and whose work was published in two anthologies edited by Neal E. Lambert and Richard H. Cracroft, A Believing People (1974) and 22 Young Mormon Writers (1975). She was killed in an automobile accident, by a drunk driver, returning home from BYU near the end of her senior year. Lambert and Cracroft remarked that she was “a creative writing student with brilliant promise.” In her honor, the English Department created the Ann Doty Memorial Award, (also known as the Ann Doty Short Fiction contest), an annual award which still exists, open to BYU undergraduate and graduate students, with a cash award of $300.

[5] Ann Doty (1948-1971). A BYU English student from Logandale, Nevada, who was the editor of Wye magazine, and whose work was published in two anthologies edited by Neal E. Lambert and Richard H. Cracroft, A Believing People (1974) and 22 Young Mormon Writers (1975). She was killed in an automobile accident, by a drunk driver, returning home from BYU near the end of her senior year. Lambert and Cracroft remarked that she was “a creative writing student with brilliant promise.” In her honor, the English Department created the Ann Doty Memorial Award, (also known as the Ann Doty Short Fiction contest), an annual award which still exists, open to BYU undergraduate and graduate students, with a cash award of $300.

“Stirling and Jenny” (poem). A Believing People, 1974.

“I Don’t Think Anymore it is Such a Big Deal” (short story) and “Prodigal” (poem). 22 Young Mormon Writers, 1975.

[6] The main English-language LDS Church periodicals in the 1930-1970 period were The Improvement Era (for the general LDS audience), The Relief Society Women (for adult women), The Instructor (for the Sunday School), and The Children’s Friend (for primary children). The magazines were reorganized in 1970, when The Ensign, The New Era, and The Friend were created.

[7] Edward A. Geary (b. 1937) is an emeritus professor of English and director of the Charles Redd Center for Western Studies at Brigham Young University. A native of Huntington, in southern Utah, he was educated at the College of Eastern Utah, BYU, and Stanford, where he was awarded a Ph.D. in 1971. His publications include Goodbye to Poplarhaven: Recollections of a Utah Boyhood (University of Utah Press, 1985), a collection of essays about growing up in Huntington, which was honored with an AML Personal Essay Award, and is considered a classic of Mormon literature. Also, The Proper Edge of the Sky: The High Plateau Country of Utah (1992) and A History of Emery County (1996). He has served as Chair of the BYU English Department, chair for the Utah Centennial County History Council, book review editor and associate editor of Dialogue, and, in 1984-1985, president of the Association for Mormon Letters, an organization of which he was a founding member.

[7] Edward A. Geary (b. 1937) is an emeritus professor of English and director of the Charles Redd Center for Western Studies at Brigham Young University. A native of Huntington, in southern Utah, he was educated at the College of Eastern Utah, BYU, and Stanford, where he was awarded a Ph.D. in 1971. His publications include Goodbye to Poplarhaven: Recollections of a Utah Boyhood (University of Utah Press, 1985), a collection of essays about growing up in Huntington, which was honored with an AML Personal Essay Award, and is considered a classic of Mormon literature. Also, The Proper Edge of the Sky: The High Plateau Country of Utah (1992) and A History of Emery County (1996). He has served as Chair of the BYU English Department, chair for the Utah Centennial County History Council, book review editor and associate editor of Dialogue, and, in 1984-1985, president of the Association for Mormon Letters, an organization of which he was a founding member.

[8] Carol Lynn Pearson (b. 1939) is one of the best-known and best-loved Latter-day Saint literary authors. She writes in a wide variety of genres, including poetry, theater, novel, and non-fiction. She graduated from Brigham Young University with an MA in theatre, taught for a time at Snow College and BYU, and was then hired by the BYU motion picture studio to write educational and religious screenplays. Herhusband Gerald created a company called “Trilogy Arts” and published her first book of poetry, called Beginnings in 1968. This work was a great success, and led to a series of poetry collections, including The Search, The Growing Season, and Women I Have Known and Been.

[8] Carol Lynn Pearson (b. 1939) is one of the best-known and best-loved Latter-day Saint literary authors. She writes in a wide variety of genres, including poetry, theater, novel, and non-fiction. She graduated from Brigham Young University with an MA in theatre, taught for a time at Snow College and BYU, and was then hired by the BYU motion picture studio to write educational and religious screenplays. Herhusband Gerald created a company called “Trilogy Arts” and published her first book of poetry, called Beginnings in 1968. This work was a great success, and led to a series of poetry collections, including The Search, The Growing Season, and Women I Have Known and Been.

She numerous educational motion pictures, including Cipher in the Snow (1973), as well as many plays and musicals, including the frontier-era The Order is Love (1971), the Godspell-like My Turn on Earth (1977), and The Dance (1981), which was later adapted into a feature film. She both wrote and performed a one-woman play, Mother Wove the Morning (1989), and wrote Facing East (2007), which tells the story of a Mormon couple dealing with the suicide of their gay son. It had runs Off-Broadway and in San Francisco, and was awarded an AML Drama Award.

In 1986 Random House published Carol Lynn’s memoir Goodbye, I Love You, which became a best-seller. It centered on the story of her marriage to Gerald, his homosexuality, their divorce, and his tragic death from AIDS some years later.

Carol Lynn has also written dozens of other books, including novels, diary excerpts, humor, non-fiction, and a series of inspirational books under the series title Fables for Our Times. She was given an AML “Special Award” in 1984, and the AML Lifetime Achievement Award in 2019. Among her recent books are the non-fiction The Ghost of Eternal Polygamy, which critically examines the impact of LDS ideas about polygamy, and was a finalist for the 2018 AML Religious Non-Fiction Award, and the 2022 novella The Love Map.

[9] Richard H. Cracroft (1936-2012), was born in Salt Lake City, received his bachelor’s degree in English from the University of Utah in 1961; an M.A. in English in 1963, and his Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin–Madison in 1970. At the University of Utah he studied Western literature under Don Walker (1917-1980) with his close friends Neal Lambert and Levi Peterson. He was a professor of English at Brigham Young University, where he eventually served as chair of the department and dean of the college. He was one of the most important and active critics of Mormon literature. He edited (with Neal Lambert) two anthologies of Mormon Literature, A Believing People: Literature of the Latter-day Saints, published in 1974 to be a textbook for the Mormon Literature class, and 22 Young Mormon Writers (Communications Workshop, 1975). He also edited Twentieth-Century Western American Authors (Gale Group, 1999). He was a founding member of the Association for Mormon Letters, attending the first organizing meetings, and was AML president in 1991-1992. His AML presidential address, “Attuning the Authentic Mormon Voice: Stemming the Sophic Tide in LDS Literature,” encouraged Mormon writers to preserve the living, spiritual “essences” of Mormonism in their writing. He served as the director for the Center for Christian Values in Literatureat BYU. His monthly “Book Nook” column in BYU Magazine helped to readers to the best of current Mormon literature. In 2000 Cracroft was granted honorarly lifetime membership in the Association for Mormon Letters.

[9] Richard H. Cracroft (1936-2012), was born in Salt Lake City, received his bachelor’s degree in English from the University of Utah in 1961; an M.A. in English in 1963, and his Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin–Madison in 1970. At the University of Utah he studied Western literature under Don Walker (1917-1980) with his close friends Neal Lambert and Levi Peterson. He was a professor of English at Brigham Young University, where he eventually served as chair of the department and dean of the college. He was one of the most important and active critics of Mormon literature. He edited (with Neal Lambert) two anthologies of Mormon Literature, A Believing People: Literature of the Latter-day Saints, published in 1974 to be a textbook for the Mormon Literature class, and 22 Young Mormon Writers (Communications Workshop, 1975). He also edited Twentieth-Century Western American Authors (Gale Group, 1999). He was a founding member of the Association for Mormon Letters, attending the first organizing meetings, and was AML president in 1991-1992. His AML presidential address, “Attuning the Authentic Mormon Voice: Stemming the Sophic Tide in LDS Literature,” encouraged Mormon writers to preserve the living, spiritual “essences” of Mormonism in their writing. He served as the director for the Center for Christian Values in Literatureat BYU. His monthly “Book Nook” column in BYU Magazine helped to readers to the best of current Mormon literature. In 2000 Cracroft was granted honorarly lifetime membership in the Association for Mormon Letters.

[10] Clinton F. Larson (1919-1994). Larson was born in American Fork, Utah. He attended the University of Utah, served as an LDS missionary in England in England and New England in 1939-1941, where he was influenced by the speaking style of his mission president, Hugh B. Brown, and served in the Army Air Corps in 1942-1945. After the war he completed his bachelors, earned a master’s at the University of Utah, and became a professor of English at BYU. In 1956 he received a PhD in English at the University of Denver. He became the BYU’s poet-in-residence, a position he retained until his retirement in 1985. Terry Givens has written that Larson was “the founder of a genuine Mormon poetic tradition, skirting both overt evangelizing and modern cynicism.“

[10] Clinton F. Larson (1919-1994). Larson was born in American Fork, Utah. He attended the University of Utah, served as an LDS missionary in England in England and New England in 1939-1941, where he was influenced by the speaking style of his mission president, Hugh B. Brown, and served in the Army Air Corps in 1942-1945. After the war he completed his bachelors, earned a master’s at the University of Utah, and became a professor of English at BYU. In 1956 he received a PhD in English at the University of Denver. He became the BYU’s poet-in-residence, a position he retained until his retirement in 1985. Terry Givens has written that Larson was “the founder of a genuine Mormon poetic tradition, skirting both overt evangelizing and modern cynicism.“

Larson’s published work include his lyric plays the plays Coriantumor and Moroni (BYU Press, 1962), The Mantle of the Prophet, and Other Plays (Deseret Book, 1966), and The Prophet (Chapman, 1971). His poetry collections include The Lord of Experience (1967), Counterpoint (1973), The Western World (1978),Selected Poems of Clinton F. Larson (1988), and The Civil War Poems (1989) (all published by BYU Press). He also wrote the text for the popular Illustrated Stories from the Book of Mormon. Larson expresses his ideas about Mormon literature in detail in this 1969 Dialogue interview.

Larson’s published work include his lyric plays the plays Coriantumor and Moroni (BYU Press, 1962), The Mantle of the Prophet, and Other Plays (Deseret Book, 1966), and The Prophet (Chapman, 1971). His poetry collections include The Lord of Experience (1967), Counterpoint (1973), The Western World (1978),Selected Poems of Clinton F. Larson (1988), and The Civil War Poems (1989) (all published by BYU Press). He also wrote the text for the popular Illustrated Stories from the Book of Mormon. Larson expresses his ideas about Mormon literature in detail in this 1969 Dialogue interview.

Eugene England, in his 1982 article, “Dawning of a Brighter Day: Mormon Literature after 150 Years,” wrote, “Clinton Larson was the first real Mormon poet, the groundbreaker for the third literary generation in achieving a uniquely Mormon poetic, and is still, by virtue of both quantity and quality of work, our foremost literary artist. He is a writer I respect and love for both his genius and his personal sacrifice in making his difficult and costly way essentially alone. Certainly only a part of his work is first-rate, but he has a significant number and variety of poems that will stand with the best written by anyone in his time: for instance ‘Homestead in Idaho,’ which captures with great power unique qualities of our pioneer heritage –that intense, faith-testing loneliness and loss, that incredible will to take chances and their consequences, even to be defeated, the challenge posed by experience to our too easy security within the plan, and seeing how the tragic implications of our theology are borne out in mortality. And Larson’s range goes all the way from that long narrative work to a perfectly cut jewel like ‘To a Dying Girl’ . . . [which] develops, with the ultimately irrational, unanalyzable poignancy of pure lyricism, the same theme that preoccupied Emily Dickinson in her finest work—the incomprehensible imperceptible change of being from one state to another, symbolized most powerfully for her in the change of seasons but felt most directly in the mysterious, adamant change of death.” Nate Oman, William Morris, Dennis Clark, Levi Peterson, and others debate Eugene England’s contention that “To a Dying Girl” is “the best Mormon poem ever written” at Times and Seasons in 2007.

[11] Neal E. Lambert (b. 1934) grew up in Fillmore, Utah. He earned a bachelor’s degree at the University of Utah, where he studied Western literature under Don Walker (1917-1980) with his close friends Richard H. Cracroft and Levi Peterson. He continued his studies at Utah through a Ph.D. in American Studies, writing his dissertation on the western author Owen Wister. He taught at what is now Weber State University, then joined the BYU English Department faculty in 1966. He edited (with Richard Cracroft) two anthologies of Mormon Literature, A Believing People: Literature of the Latter-day Saints, published in 1974 to be a textbook for the Mormon Literature class, and 22 Young Mormon Writers (Communications Workshop, 1975). He was a founding member of the Association for Mormon Letters, and was the second AML president in 1977-1978. He served as the chair of BYU’s American Studies Program, Associate Academic Vice President for graduate studies and research (1982-1985), and chair of the English Department (1991-1994) . From 1987 until 1990 he was president of the North Carolina Raleigh Mission. During his tenure as English Department Chair, BYU faced debates over the extent of dissent allowed by faculty from LDS teachings, especially in the English Department. You can read a 2022 interview Andrew Hall held with Neal Lambert here.

[11] Neal E. Lambert (b. 1934) grew up in Fillmore, Utah. He earned a bachelor’s degree at the University of Utah, where he studied Western literature under Don Walker (1917-1980) with his close friends Richard H. Cracroft and Levi Peterson. He continued his studies at Utah through a Ph.D. in American Studies, writing his dissertation on the western author Owen Wister. He taught at what is now Weber State University, then joined the BYU English Department faculty in 1966. He edited (with Richard Cracroft) two anthologies of Mormon Literature, A Believing People: Literature of the Latter-day Saints, published in 1974 to be a textbook for the Mormon Literature class, and 22 Young Mormon Writers (Communications Workshop, 1975). He was a founding member of the Association for Mormon Letters, and was the second AML president in 1977-1978. He served as the chair of BYU’s American Studies Program, Associate Academic Vice President for graduate studies and research (1982-1985), and chair of the English Department (1991-1994) . From 1987 until 1990 he was president of the North Carolina Raleigh Mission. During his tenure as English Department Chair, BYU faced debates over the extent of dissent allowed by faculty from LDS teachings, especially in the English Department. You can read a 2022 interview Andrew Hall held with Neal Lambert here.

[12] Marilyn McMeen Miller, now known as Marilyn Brown (b. 1938), was born in Denver, and lived in Bremerton and Provo as a child. She earned both a B.A. and M.A. in English from BYU, and one the first Mayhew writing prize in 1962. Besides her writing, she also painted and played flute in the BYU orchestra. She married the talented but unstable jazz musician Lloyd Miller, who later gained some fame for his work melding Persian and other Asian native musical traditions with jazz. They

[12] Marilyn McMeen Miller, now known as Marilyn Brown (b. 1938), was born in Denver, and lived in Bremerton and Provo as a child. She earned both a B.A. and M.A. in English from BYU, and one the first Mayhew writing prize in 1962. Besides her writing, she also painted and played flute in the BYU orchestra. She married the talented but unstable jazz musician Lloyd Miller, who later gained some fame for his work melding Persian and other Asian native musical traditions with jazz. They  divorced by 1967, and her first book, the poetry collection Rainflowers, was published in 1969. She published three other poetry collections in the following years. After her marriage to Bill Brown in 1975, she launched into a career writing novels, starting with The Earthkeepers, a historical novel about the settling of Provo, which won the 1981 AML fiction award. Among her many other novels are Goodbye, Hello (1984), Statehood (1995), The Wine-Dark Sea of Grass (2000), House on the Sound (2001), Serpent in Paradise (2006), and Escape from Namur (2020). She wrote the words to the hymn “Thy Servants Are Prepared,” which is included in the 1985 LDS hymnbook. She completed an MFA at the University of Utah in 1992. In 1998 she created the Marilyn Brown Novel

divorced by 1967, and her first book, the poetry collection Rainflowers, was published in 1969. She published three other poetry collections in the following years. After her marriage to Bill Brown in 1975, she launched into a career writing novels, starting with The Earthkeepers, a historical novel about the settling of Provo, which won the 1981 AML fiction award. Among her many other novels are Goodbye, Hello (1984), Statehood (1995), The Wine-Dark Sea of Grass (2000), House on the Sound (2001), Serpent in Paradise (2006), and Escape from Namur (2020). She wrote the words to the hymn “Thy Servants Are Prepared,” which is included in the 1985 LDS hymnbook. She completed an MFA at the University of Utah in 1992. In 1998 she created the Marilyn Brown Novel  Competition, recognizing unpublished novels. Together with Bill, they ran a theater in Springville from 1996 to 2004, and Marilyn wrote two musicals. In 2008 they opened the Brown Art Gallery in town. She served as Association for Mormon Letters President in 2000-2001, and in 2011 she was presented with the Smith-Pettit Award for Outstanding Contribution to Mormon Letters. She wrote about her career in a 2021 AML blog post.

Competition, recognizing unpublished novels. Together with Bill, they ran a theater in Springville from 1996 to 2004, and Marilyn wrote two musicals. In 2008 they opened the Brown Art Gallery in town. She served as Association for Mormon Letters President in 2000-2001, and in 2011 she was presented with the Smith-Pettit Award for Outstanding Contribution to Mormon Letters. She wrote about her career in a 2021 AML blog post.

In case anyone wants the full citation, the article is from the Special Supplement to The Daily Universe, Vol, 22, No. 64 from Wednesday, December 17, 1969. It appears in Box 10, Folder 14 of MSS 8107, the Victor Purdy papers: http://archives.lib.byu.edu/repositories/ltpsc/resources/upb_mss8107

You can see the rest of the supplement online! Here’s the URL: https://archive.org/details/dailyuniverse2262asso/page/n15/mode/2up

One other Mormon author and poet is Ila Marie Lytle Myer (b.1932-2005) who wrote and published many poems , short stories, and articles, and a play (Mission Call) that was performed at BYU and throughout the Church. Marie was born in St. George , Utah, received her degree in English at BYU in 1954, married Peter L. Myer in 1955 (later a BYU professor in the Art Dept.) and did graduate work at BYU towards a graduate degree in playwriting. She did publish two books of poetry: “I Turn My Heart Inside Out, ” and “Red Cliff Elegy”. The second book did contain a poem entitled “Massacre” that dealt with the subject of the mountain meadows massacre that occurred on her family’s ranch in southern Utah. She was a student of and a friend of Juanita Brooks. She studied with Clint Larsen and Leslie Norris who both wrote introductions to her books of poetry.