A guest post by Doug Gibson, cross-posted on his blog, Mormon History and Culture.

Please also see Ardis E. Parshall, Corianton: BYU Screens the Restored Movie.

Review/observations by Doug Gibson

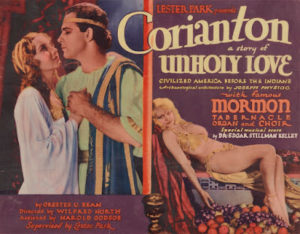

For about a couple decades, I had longed to view the early sound film “based” on a segment of The Book of Mormon. It’s Corianton: A Story of Unholy Love, 1931. With artistic license, it tells of Alma’s somewhat troublesome son, Corianton, and his involvement with the harlot, Isabel. This is all part of Alma’s letters to Corianton in Book of Alma, chapters 39-42.

Now that’s not Isabel reclining and wearing very little in the poster above. But the woman — an extra — is in the film, and dressed as such. Corianton premiered in Salt Lake City and then promptly flopped at the box office. Ultimately, more money was likely earned by lawyers litigating over the film than at the box office. It’s a low-budget black and white film that once aspired to be in color. The Great Depression cut fundraising severely, and it limps to its climax, with the final scenes – a battle between the Zoramites and the Righteous — a mixture of stock footage from the 1922 big-budget film Sodom and Gomorrhah, and the Corianton film actors passionately fighting, arguing, and dying on what looks like a stage.

Nevertheless, I loved this film after watching a restored version that played at BYU’s Varsity Theater the last Friday of January. The BYU Motion Picture Archives hosted the event, and the Varsity Theater was packed. (Granted there was no charge, but that’s still a great crowd). Panelists — including author/historian Ardis E. Parshall, and Ben Harry, curator of BYU’s Motion Picture archives, provided commentary before and after the film.

(A lot of the back history of this film mentioned in this blog post, as well as many of its artistic merits, pro and con, was also observed by the panelists and noted in Parshall’s book. Here is one still from the film, below.)

Parshall, by the way recently edited a book — The Corianton Saga — covering the history of the Corianton story adaptations. It was first a novella by LDS General Authority B.H. Roberts, titled Corianton: A Nephite Story, then adapted into a play by an eccentric Latter-day Saint named Orestes U. Bean, who developed an obsession with the story he had appropriated from Roberts, as well as another late-19th century Book of Mormon-themed novel titled, A Ship of Hagoth, by Julia A. McDonald.

The play was titled Corianton. It played well in what is described as the “Mormon corridor,” or areas heavily populated by Latter-day Saints. When its backers took the play to parts east of the Rocky Mountain West — including New York City — it failed. In New York City, Bean titled it An Aztec Romance.

A little backstory: In the late 19th century, there was an effort from LDS leaders to create art from the Scriptures, and the church’s doctrine and its early struggles. Besides the aforementioned books that resulted, there was Nephi Anderson’s tale that included the pre-existence, Added Upon. That book was in my family’s library as I was growing up. Besides novels there were plays and short stories. I recall reading one by Anderson in which a lazy LDS teenager — too bored to attend church — was thrust into a dream where he experiences the pre-Utah persecution of the Saints. This sort of “‘Mormon Renaissance” was the precursor of the film, Corianton: A Story of Unholy Love.

I know I am meandering so I’ll try to get to the film. In the 1920s, an entrepreneur named Lester Park, after watching impressive films like Ben Hur gain notice, acclaim, and box-office money, decided that the story of Corianton would be box-office gold. The project was successful early, and even the tepid resulting film has evidences of the early money. It was filmed in New Jersey. Its music composer was from Ben Hur, The film’s orchestra music was overseen by the former head of the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra of New York City. Professional dancers were in the film, and the LDS Tabernacle Choir and Great Organ is heard in the film. I mentioned that an original idea was to shoot the film in color.

But, as mentioned, the money started to dry up. And there was a second problem; the play’s mercurial, eccentric, odd, creator, the aforementioned Orestes Bean. He had finagled himself a lot of control over the production, which caused headaches for director Wilfrid North and the film crew. In fact, a lot of the film was shot in a hurry while Bean was off getting married, and absent from the set.

Corianton starts with the trial of Korihor. Corianton is a fan of the apostate, and critic of his father Alma. His faith is re-energized once he sees Korihor struck dumb and he goes off on his mission, with his brother Shiblon. Once with the Zoramites, though, he becomes too friendly with Zoramite nobleman, Prince Seantum. Seantum conspires with his mistress, Isobel, to get Coriantumr infatuated with her. The plan, which works to perfection, lures Coriantumr to a swinging Zoramite party where he’s fed lots of wine by Isobel. Once his drunkeness is publicized by Seantum and others, the reputation of the missionaries is tarnished.

Prince Seantum is not in The Book of Mormon. Nor is a woman named Relia, a pious woman who is engaged to Shiblon but actually in love with Corianton. Meanwhile, Isobel, despite her treachery, falls in love with Corianton, who feels regret at what he has done. This all really upsets Seantum, who plots not only the murder of Corianton and Isobel, but plans to lead an army and destroy the righeous Nephites. The climax of the film is that battle.

I’m conditioned not to reveal the end of movies, which is kind of unfair since Harry told the audience at the Varsity Theater that there are no plans to release this film, as a DVD, or on YouTube, or on TV. However, interested readers can purchase the book Parshall edited, as it contains the entire film script.

This is not a traditionally good movie. I would give it 1.5 stars out of 4. But it’s still so interesting to watch. If I could, I’d buy 40 copies and give them to likeminded friends. As Harry noted, “(the film) is a holdover from an earlier era.” Pomp and majesty, and drama, and very loud talking is how the film conveys its religious message. It’s not like films today which focus on emotion and deep spirituality to convey a religious message. As Harry noted, it’s a lot like Ben Hur was in its religious delivery.

“We need to watch with one eye in 1931 and one eye in 2023,” Harry added. (See another still from the film below.)

My opinion of the film is that it mixes three different artistic styles, the creaky, still under-developed sound technology of 1931, the pantomime, emotional style of silent cinema, and the loud, let’s-project-our-voice-through-the-auditorium of the traditional stage. (Harry also noted a couple of these observations.)

Much of the overly emotional, tragedian (particularly from the actor who played Shiblon) acting in the film is risible today, and there were a dozen-plus incidents in the film that evoked respectful laughter.

As was noted by Parshall, an unhealthy influence of too much Orestes Bean found itself into the script as the film progresses. Suddenly, the actors started to talk in a Shakespearean manner. “(Bean liked) thees and thous,” Parshall told the audience. Parshall does note that these were talented artists, on both sides of the camera.

Much of the film’s faults are due to the lack of money as filming progressed. The “Beanish” script didn’t help, and the normal-for-the-times overly dramatic, tragedy-like lamenting over-acting doesn’t go over well today, and invites giggles from the audience. Those who have read The Book of Mormon, I feel comfortable saying, won’t see “Korihor,” or “Alma,” in the actors on the screen.

One favorable note for this film is it underscores the progressive nature of Mormonism when it comes to salvation. During the climax, actors express their confidence that God will forgive them of their sins, accept their repentence, and welcome them to heaven. In fact, one character claims that he received revelation that Korihor had been saved.

Also, the two leads, Eric Alden as Corianton, and Theo Pennington, as Zoan Ze Isabel, are great in their roles. (In what strikes me as humorous, I learned at the film showing that Bean’s wife eventually changed her name to Zoan Ze Isabel. Bean, by the way, in the latter years of his life, lectured on his play/movie extensively in southern California, to large crowds. He had a missionary zeal for it.)

Finally, I want to mention one more interesting fact about Corianton: A Story of Unholy Love. It’s a fairly racy film, although that was not uncommon in that film era. There are many dancers dressed like the woman in the above poster. And there is a scene, where an angry Corianton is confronting a penitent Isobel, where Theo Pennington is visibly nude under a thin negligee. One panelist, I cannot recall which, did opine that box office receipts likely dropped after parents had second thoughts about children attending. Frankly, the film would probably garner a PG or PG-13 today, or soft R if the MPAA was in a prudish mood.

I am so glad I saw this historical gemstone. It has so much much value, particular for the cultural history of Mormonism. I appreciate Parshall, Terry and others for publicizing the film and restoring it. It played a decade or so ago at BYU but I missed it. This newer restored version include subtitles, which was helpful. The audience clearly appreciated the film. Harry promised the film will eventually get another showing, and said that a new print has been discovered in California, under a different title.

(Below, one more still/poster, with the leads “Corianton” and “Isobel.”)

.

A second print! A second title! Oh, innnnteresting. I wonder if it’ll otherwise be the same cut.

Great Review, it sounds like a fascinating movie, let your followers know when it has another showing!

Carla smith