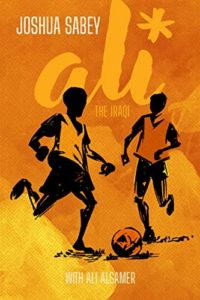

Joshua Sabey on his new novel, Ali: The Iraqi (BCC Press, 2023), written with Ali Alsamer.

Joshua Sabey on his new novel, Ali: The Iraqi (BCC Press, 2023), written with Ali Alsamer.

As we pass the twentieth anniversary of the US military invasion into Iraq and another Ramadan is upon us, I am reflecting on my early religious insecurities brought to light by a Muslim boy named Ali, a history which I have enumerated and fictionalized in a book named in his honor and written with his consultation.

The summer of my junior year in High School, my parents attended a meeting about a student exchange program. It was a short program, two or three weeks. Each family would host two Iraqi high school students. They would come from all over Iraq: Baghdad, Basra, Kurdistan . . .

In preparation, we had a few meetings with a man who had lived in the Middle East and spoke Arabic. He taught us things like having a picture of water or minimally some wet wipes in our bathrooms so that the students could perform Wudu. He taught us about the prayer times and other things to expect and make room for.

Ali was assigned to stay with us. He was slim, athletic, and seemed to come with all the fixtures of a deeply religious upbringing.

But by the end of the trip, he no longer performed the prayers. And several of the girls who were staying with other families had taken off their hijabs. It was strange. We had expected and prepared for an encounter with Islam. But it was as if the old and beautiful religion was something that could and had been taken off. And as a religious boy myself, there was something threatening in this reality. And I began to resent him for it.

This was a strange moment for me. I both believed in my faith and planned to serve a mission to convert others, and yet I felt uncomfortable and even angry that Ali might so easily abandon the faith of his fathers. I wanted Ali to be Muslim. And that was the beginning of my book.

So much of this book was a method of exploring religion, belief, meaning. And so in a very real way, I was using Ali’s story to write my own. And while that probably sounds pretty ego-centric, I actually believe it’s unavoidable. And what’s more, I don’t think it’s entirely regrettable. There is something beautiful about the fact that we lean into each other. That our stories and agencies are all intertwined. And when we move, it is not through empty space, but through one another.

In a real way, I believe this sort of interfaith inter-connection is simply the state of affairs. Even within a faith, we borrow from across the aisle, we bolster, commune and share identity even from unknown and disparate places.

While there are valid reasons for division between faiths, in many ways we are always in communion. Interfaith is more than inter-toleration, inter-respect, or even inter-collaboration. Interfaith, in a real way, is like having a brother. There are some different genetics and predispositions, but a shared work. And the work is loving and living in the world together. It’s getting past pride and jealousy so we can be a pillar when the world is crumbling, to share meals and conversations after a hard day, to have a place to spend holidays. Interfaith work, ultimately, is the work of bringing God’s family together as a family, like we’re not just pretending.

This is something I came to believe as we went with Ali to mosque and he came with us to church. We fasted Ramadan and Fast Sundays together, and engaged with the principles of Islam and Mormonism under the same roof.

You can get a sense for how this played out by reading the excerpt below:

Later Dad will tell me why he believes it is right for Ali to remain Muslim. He will invite me into his room and sit me on the edge of the bed, his computer across his lap, and read a line from his journal:

Ali has an old faith and an old country and we have a new faith and new country. If we were to convert all of the Muslims, that would be the end of us. Their culture is too old, we would be the ones that were assimilated. We might not even know it but we would become Islam like Christianity became Rome.

“Can it still be true, in the way we mean when we say it is true?” I ask.

“True? Yes it is true. You mean is it weltherrschaft. It is true. Not now. But eventually, yes. I think so.”

When I fall asleep, I dream of Ali as if he had been a prophet.

A man stands between heaven and earth. There is no turning from him. In all directions it is the same: the man, wreathed in light, one leg on the eastern horizon and one on the western horizon. That is what the boy remembers. It had been certain. But the man is gone and the boy stands making images on the wall. He paints one leg on one wall then walks across to the opposite side of the cave and paints the other. Later, he will join them together and they meet in the middle. He feels that for a moment he had seen everything, and that now he must capture as much as possible before it escapes him. He hops, jumps, and scampers around the cave as though he is capturing lightning bugs against the wall. He writes incomplete sentences because whenever he begins one, he suddenly remembers another and moves to a different wall to begin the new sentence. He figures if he starts the sentence he will be able to finish it later, even if the old memory has disappeared, displaced by the new.

He knows it is always the beginning of the sentence that is impossible—that requires inspiration. But the boy was able to finish well enough by himself. He is years this way. Writing images, descriptions, and poetry. Until there is no room on the walls anymore. And it is then, at the completion, that he is surprised to find himself possessed by doubts. He has finished the sentences, but the memory has now gone entirely. How was he to know if the end was correct, or if it had all been made up: all the endings required the truthfulness of the beginning, which now seems as suspect as the correctness of the end. The boy weeps against the wall and his tears run down the rock erasing a small line as it travels.

Joshua Sabey is a documentary filmmaker and writer. His writing has won various awards including the Ann Doty Short Fiction Contest, the McKay Essay Contest, and the Mayhew Creative Arts Contest. His recent film, American Tragedy, won Best Documentary at the Boston Film Festival and was among the top 20 most watched documentaries on Amazon. He lives in rural Idaho with his wife and two boys. Ali the Iraqi is his debut novel.

Recommendations of the book:

“Josh Sabey’s Ali is a masterful depiction of friendship and faith, tradition and culture, and the very real power of storytelling itself. It brilliantly shows what it means to call someone a friend and a brother. And what it means to truly share yourself with that person, to learn from them, to depend on them. It is a remarkable portrait of love and empathy and grace.”

—Stephen Tuttle

“This is a bi-cultural Bildungsoram novel, with semi-fictional protagonists, Ali and Paul, are working through their relationships to their cultures, their faiths, their families, and each other . . . This book asks probing questions about sacred spaces, what we may claim as our own, and what we should not claim. It looks at grief, passion, love, and coming-of-age with raw candor but also with tenderness. The writing itself is often transcendent.”

–Margaret Blair Young