Ryan Ward introduces his new book, And There Was No Poor Among Them: Liberation, Salvation, and the Meaning of the Restoration (Greg Kofford Books), which will be released May 16.

Theology is formed and adapted in response to crisis. Perhaps the prototypical theological crisis, although not often thought of as such, is the destruction and captivity of Israel by Babylon. Why was this a theological crisis? Israel had received a covenant promise that they would be a great nation and would fill the earth. Now, their temple was destroyed, their people slaughtered, scattered, and in captivity. How were they to understand God’s action in their history and what those promises meant for their future? The biblical writers and compilers reckoned with these questions.

Theology is formed and adapted in response to crisis. Perhaps the prototypical theological crisis, although not often thought of as such, is the destruction and captivity of Israel by Babylon. Why was this a theological crisis? Israel had received a covenant promise that they would be a great nation and would fill the earth. Now, their temple was destroyed, their people slaughtered, scattered, and in captivity. How were they to understand God’s action in their history and what those promises meant for their future? The biblical writers and compilers reckoned with these questions.

In more recent times, the second World War precipitated a massive theological crisis, particularly for the Jewish community. The horrors of the Holocaust gave rise to the question, asked in various forms and iterations: “How does one do theology after Auschwitz?” The tragedy and trauma were so great and flew so much in the face of traditional notions of God that the Jewish theologian Richard Rubenstein provocatively stated that the only logical response to the horrors of the concentration camps was that the God of Israel was dead. The author Elie Wiesel wrestled with similar notions. How is God and God’s plan for humanity to be understood in the face of such a crisis?

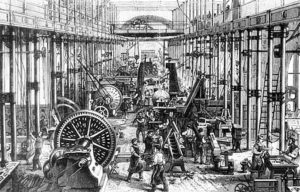

I wrote And There Was No Poor Among Them in response to what I view as the major theological crisis of our time. I refer to the rise and globalization of unfettered capitalism. This book is my attempt to answer the question of how to do theology in the face of this historical reality, often sugarcoated or twisted by propagandists. What does a Latter-day Saint theology look like after colonialism? How do we do theology after the Industrial Revolution? How do we do theology in the face of millions of starving, exploited, and immiserated poor? How do we do theology in the face of an imminent climate disaster caused by the greed of fossil fuel corporations? Our theological explorations must reckon with these realities if we are to help our community find meaning amidst these challenges. As a church, we have been very good at differentiating ourselves from other Christian groups and forming a theology of our privileged authority and role in the world. Being predominantly focused on apologetics and the next life, however, we have not been very good at developing a theology that deals with the real problems of history and their ongoing effects in our contemporary society. This book is my attempt to begin to explore such a theology.

I never planned to write a book, let alone one about a Latter-day Saint theology. I am an experimental psychologist/neuroscientist by training. I write scientific articles, not religious books. For the last several years, I became passionate about the idea of salvation, but not salvation as I had typically thought of it. I pored over what my kids referred to as “Jesus books,” as well as history books about the rise of capitalism. There seemed to be a connection between Jesus’s ministry of liberating the captive and oppressed and the mission and mandate of the

Church in the context of the suffering, exploitation, and inequality that has resulted from the globalization of capitalism, but I couldn’t quite see it. Then one day it hit me. 1820. The year of the beginning of the Restoration, and the year of the height of the Industrial Revolution. The same year. What if the Restoration was an explicit response by God to the Industrial Revolution and the rise of capitalism? Surely someone had written about this. Nope.

Church in the context of the suffering, exploitation, and inequality that has resulted from the globalization of capitalism, but I couldn’t quite see it. Then one day it hit me. 1820. The year of the beginning of the Restoration, and the year of the height of the Industrial Revolution. The same year. What if the Restoration was an explicit response by God to the Industrial Revolution and the rise of capitalism? Surely someone had written about this. Nope.

The book came together over the course of five months. I wrote for a couple hours in the morning each day, before I got ready for work. Sometimes I would wake up in the middle of the night with ideas and couldn’t sleep. Everything I had read about Jesus, Christianity, history, and economics over the past 10 years surfaced and organized itself on the page. At the risk of sounding cliche, the book wrote itself. It attempts to show how in past centuries, the Christian idea of salvation has specifically been related to temporal liberation and justice, particularly for the poor and oppressed. This understanding has changed over the course of Christian history to our current spiritual view of salvation as redemption from individual sins. The historical timing of our own Restoration tradition lays the groundwork for us to reclaim this expansive idea of salvation as liberation from anything that prevents human flourishing in this life. In particular, the idea of a Zion community serves as a prototype for what we should be striving for in our own communities, nations, and the world. This vision of community stands in stark contrast to the individualism prized and reinforced by the social and economic systems of today.

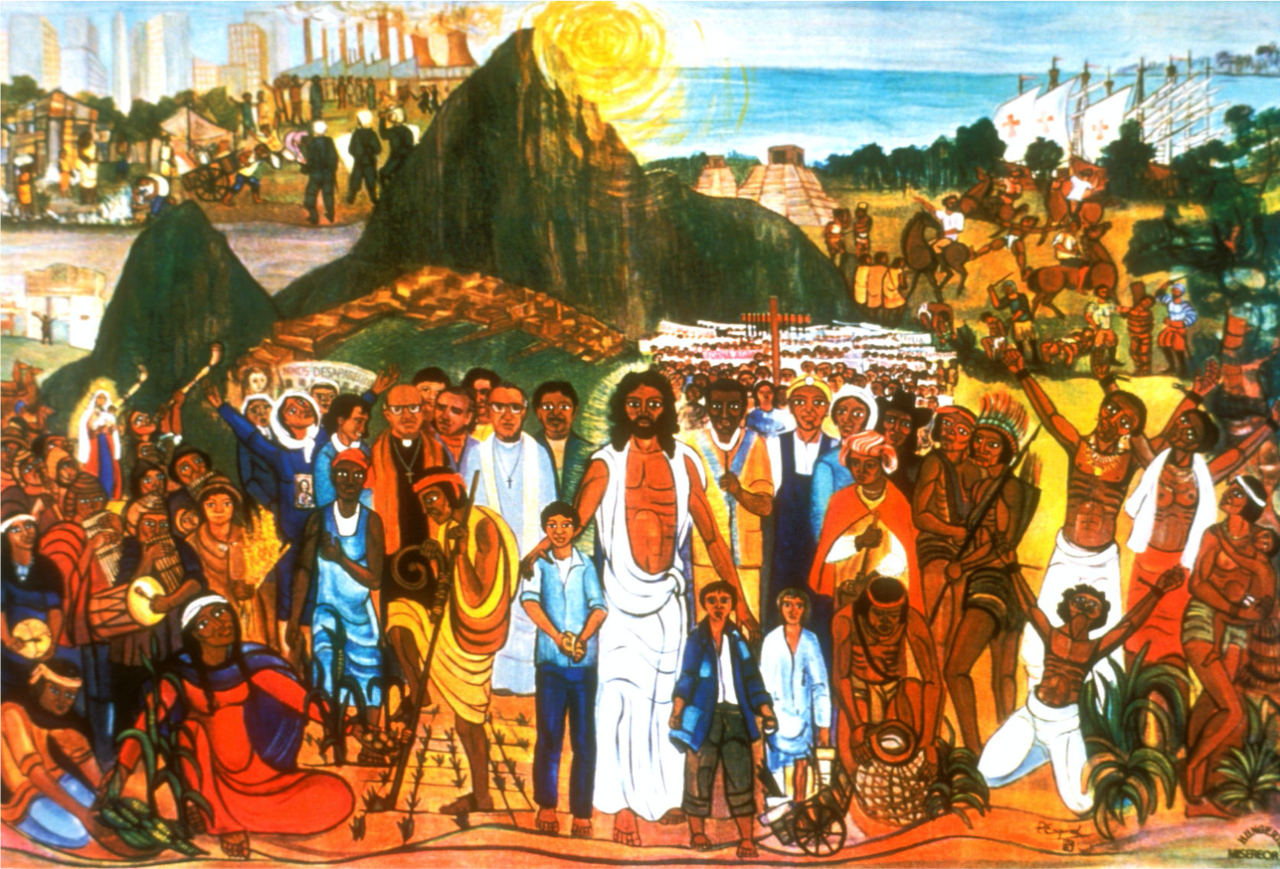

I have drawn inspiration from a branch of Christian theology known as liberation theology. This theology was worked out in the 1960s and 70s by Catholic clergy in Central and South America in response to the brutal dictatorships of these decades. These dictatorships were often supported, and in many instances, installed by the United States, in an effort to protect their economic interests. Liberation theology deals with the very difficult question of how to understand the gospel as “good news” in contexts of oppression, poverty, and suffering. It views God’s salvation as being specifically related to liberating the poor and oppressed in this life, not only to a spiritual inheritance in the next. It is written from the perspective of the victims of oppression and rejects easy answers and traditional formulations and understandings of God, Jesus, and the church. It is truly radical. Radical in a way that has provided hope for millions of suffering poor, and radical in a way that is desperately needed in our current day and age.

I realize that many will have a knee-jerk reaction to reject this position and framing of the Restoration. The politics of our current day often reject discussions of justice and equity as “Marxist” propaganda. Liberation theology is painted absurdly as “anti-Christ.” I hope that my book will provide a useful and accurate introduction to this profound strand of theology. I hope it provides some food for thought and that even those that disagree with my position will at least take the questions I pose seriously. I hope the book contributes to ongoing and necessary conversations about how to place our religious tradition in its appropriate historical, political, and social context, and how to grapple with its past, present, and potential future relevance for a suffering world. I hope it provides a new lens through which Latter-day Saints can view their faith and allows us to begin to expand our vision of what salvation can be. Most importantly, I hope it inspires us to take seriously our covenant obligation to the poor, oppressed, and marginalized, an obligation that requires us to realize our liberative potential as the body of Christ in the world.

Ryan Ward received his PhD from Utah State University specializing in experimental psychology. Following postdoctoral work in the Departments of Psychiatry and Neuroscience at Columbia University in New York City, he accepted a position at the University of Otago, where he is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Psychology. His research focuses on the neural basis of learning, animal models of psychiatric disease, and motivations for drug use. He teaches courses on drugs, behavior, addiction, and policy, and research methods. He lives with his wife and five children in New Zealand.

Ryan Ward received his PhD from Utah State University specializing in experimental psychology. Following postdoctoral work in the Departments of Psychiatry and Neuroscience at Columbia University in New York City, he accepted a position at the University of Otago, where he is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Psychology. His research focuses on the neural basis of learning, animal models of psychiatric disease, and motivations for drug use. He teaches courses on drugs, behavior, addiction, and policy, and research methods. He lives with his wife and five children in New Zealand.

One thought