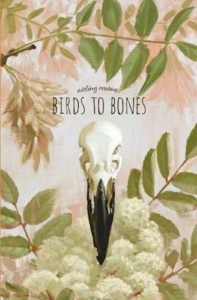

Ailing Rowan introduces his new book, Birds to Bones: Writings on Grief, Gender, Mormonism, and Magic (BCC Press).

Ailing Rowan introduces his new book, Birds to Bones: Writings on Grief, Gender, Mormonism, and Magic (BCC Press).

(content warning: mentions of infant death and suicidal ideation)

Mormons, in my experience, aren’t very good with grief.

We mobilize expertly in moments of crisis, having refined the art of the casserole, Relief Society sign-up sheets, and luncheons in the cultural hall after a funeral. When it comes to inner wounds, though, the offerings are primarily platitudes. I heard them in church hallways and classrooms after the deaths of my baby brother and, later, my baby sister: “It was Heavenly Father’s plan!” “They just needed to come here for a body!” “God had work for them on the other side!” “It would be more sad if they’d been older!” Oddly, these didn’t bring much actual comfort (except, maybe, to the one speaking). Mormonism just didn’t seem able to hold space for my aches of here-and-now.

Fair enough: grieving is uncomfortable. It’s challenging, devastating, and can become all-consuming. God forbid, it could turn you bitter. So even privileged as I was with resources like peer support groups, I didn’t want to constantly exist in that space either. Instead, I decided, I’d compartmentalize, process it, and get on with things. I just wanted to be a kid.

It became second nature to bury my sadness, confusion, questioning, and fear beneath promises of hope. (I didn’t let myself get anywhere near anger.) Since I agreed that I’d someday be reunited with my whole family forever, the sting of bereavement could be bartered away as something only temporary, or unjustified. Jesus had already conquered the grave–rejoice!

As it turns out, shoveling dirt over your soul for half your life is suffocating. A blanket of mud can create the perfect conditions for things to calcify, by choking out the microbial forms of life that assist with decay. (Decomposition gets a bad rap–it’s only another segment of the eternal round, a crucial piece in creation’s eventual restoration.) There is so much I had to return to and excavate in my adult body. And the creative writing course I took at BYU, while in the throes of deep depression, turned out to be fertile ground for discovering fossils. Eventually, I found myself down a rabbit hole, taking my whole identity–and my entire belief system–all the way back to bedrock, ready to reconstruct everything I thought I ever knew. This time, with authenticity and intention.

Birds to Bones is the result of that initial decade of accumulation, and the following decade of sifting back through it. Rather than a singular straightforward narrative, this book is what I’ve been calling “the underside of a memoir.” While it does explore a particular epoch in my life, it does so in fragments, sometimes contradicting itself and not in chronological order. There were times I gave everything to God with devoted praise, and stretches of wondering where the hell God was, if he was even there to begin with. In anguishing instants I sometimes wanted to be dead, but thinking about dying would also paralyze me with anxiety, and anyway isn’t it such an improbable joyous miracle to even be here at all? Life isn’t a clean, tidy story, and all these parts of me once lived, often overlapping. We all metamorphize like rocks in the molten earth, like seashells and skeletons shifting into limestone–never constant, only observed in discrete moments.

Birds to Bones is the result of that initial decade of accumulation, and the following decade of sifting back through it. Rather than a singular straightforward narrative, this book is what I’ve been calling “the underside of a memoir.” While it does explore a particular epoch in my life, it does so in fragments, sometimes contradicting itself and not in chronological order. There were times I gave everything to God with devoted praise, and stretches of wondering where the hell God was, if he was even there to begin with. In anguishing instants I sometimes wanted to be dead, but thinking about dying would also paralyze me with anxiety, and anyway isn’t it such an improbable joyous miracle to even be here at all? Life isn’t a clean, tidy story, and all these parts of me once lived, often overlapping. We all metamorphize like rocks in the molten earth, like seashells and skeletons shifting into limestone–never constant, only observed in discrete moments.

I gathered these writings and drawings together as a testament, and a monument: despite it all, I existed, I lived, I mattered. By getting down into the nitty-gritty realities of mortality, I hope I’ve unearthed something that will outlast me, and resonate with anyone else who has ever undergone transformation, or considered their own impermanent nature, or lost someone they loved, or marveled at the strata in a cliff face and the birds wheeling above it.

I Am a Cosmos

One morning I woke, and found the sunlight in me

all mined away, ounce for ounce.

With my veins emptied, the structure fell free:

a hollow collapse. Yet I could not renounce—

I’m more than five feet and three inches of skin.

I am a cosmos. A continuous lightning strike

enclosed in a ribcage. Saltwater rivers within

pulse forward and back in the dark, and I like

to believe the stars’ Architect made me, too.

It explains why something so fragile works at all;

the immense forces this delicate system can pull through

without breaking are its own testament. I feel small

in this world where everyone around me is a world,

yet somehow significant in a greater universe unfurled.

Aisling “Ash” Rowan (they/him) is an aspiring fossil who writes at the intersections of queerness, disability, and faith. They studied illustration at Brigham Young University and founded the project GEM Stories, which shares the experiences of gender-expansive Mormons. Ash lives with his spouse and kids in the valleys of Utah (unceded Ute land), where magpies sing about home. Birds to Bones is Ash’s solo writing debut.